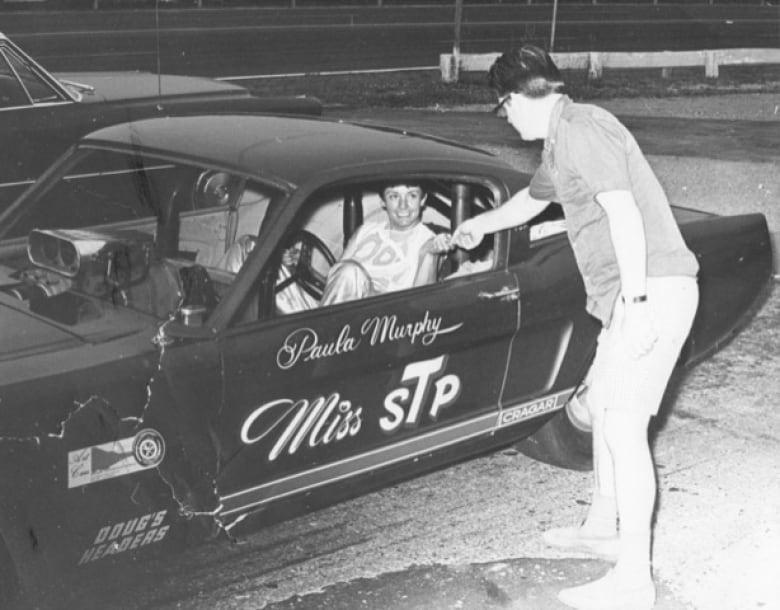

As It Happens6:00Remembering Paula Murphy

Paula Murphy was a natural-born racer, a trailblazer, and someone who refused to sit by and watch, according to director Pam Miller.

Murphy died at age 95 on Dec. 21 at an assisted living facility in Prescott, Ariz.

Murphy conquered a number of firsts during her racing career. She was the first woman to drive an Indy car, the first woman to get behind the wheel of a jet-engined car, and the first woman licensed to drive a nitromethane-fueled car.

Pam Miller interviewed Murphy while working on the documentary Paula Murphy: Undaunted. Miller spoke with As It Happens host Nil Köksal. Here’s part of that conversation.

What do you remember about doing that interview and her energy?

She had this sparkle in her eye that you see in the old film that we dug up of her. Whether she was on the [Bonneville] Salt Flats, in a jet car, in the Indy car, she had the sparkle and she still had it at 93. She still had the passion. She still had a lead foot. She still loved to drive fast.

She was unfazed by the gravity of the situations that she was put in. And even at 93, 94 years old, she was fully independent and full of challenge, and yearning for more challenge. And obviously she loved speed. She had that sparkle and passion still at 93.

That need for speed early on … how does that morph into eventually becoming a race car driver?

She tells the story when she first goes to her first sports car race and she was bored. She thought it was ridiculous. She hated watching it. And then somebody suggested that she try to to drive in a race. And from that moment on, she was hooked.

She was racing sports cars on the West Coast and she honed her craft and she learned that she was a natural.

You mentioned the race on the salt flats back in 1964. Can you tell us what happened there and how she grabbed the world’s attention?

Well, that was a speed record. That was in a jet car on the salt flats, when she couldn’t reach the pedals. They had to actually put a pillow behind her.

Think about this. She’s in this tin car with a jet engine behind her in the vast expanse of the salt flats going 300 miles an hour and she can’t reach the pedals. And she’s never been in the car before. And she gets in the car and just goes for it. And it’s wet and the car gets a little squirrely. And she’s never driven anything like it before. And she sets the record.

She did the same thing at Indianapolis when she got in the Novi for the four laps she was allowed to do, never having sat in the car before, never having seen that car before and being asked to perform at the highest level at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

You wanted to do this documentary because you felt not enough people knew about what she’d done for women and for racing and what she achieved on her own as well. Given what she was able to accomplish, why do you think Paula Murphy wasn’t more well known?

She was well known in the era. She was the woman that people look towards to do things that women hadn’t done before.

She was the first woman to run laps at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. She was also the first woman to get in a stock car at Talladega Superspeedway, which is a huge superspeedway in NASCAR.

We wanted to tell the story because she did these things without practice, without — sometimes — notice. And she was out there performing under pressure that if she had messed up at any time, whether it was on the salt flats or in Indianapolis or Daytona, there would have been a moment in time where people would have said, “Can women really do this?”

And because she was able to do it under pressure with no practice and prove that a woman can do it, women like Janet Guthrie and Lyn St. James and Danica Patrick got opportunities later on. But if she had messed up in those moments and not seized those opportunities, women could have been set back and not given opportunities that we’ve seen since.

You have some old newsreels in the documentary as well, and just how she’s characterized, how she’s being framed, they’re not being mean, but it’s certainly of the time, and it’s certainly sexist…. How did she deal with with all of that while she was focused on racing?

She was so about the opportunity. She kind of joked to me that as long as they were talking about her, she was OK with it. As long as she was getting opportunities, she was OK with it.

She just wanted the chance. And she knew there was only so far she could go. She knew she wasn’t going to be allowed to race against the guys in the Indianapolis 500 at that moment. But she wanted the chance to prove what she could do.

And she basically thought that as long as people were talking about her, she would get more and more opportunity, which was what happened for her.

I mean, she ended up being in the presence of Princess Grace [Kelly] in Monaco in the one and only Women’s Grand Prix representing the United States. And that was much later in her career because of the fact that she could live up to these expectations at a moment’s notice and perform undaunted to set these records and move the ceiling just a little bit more for the next generation.

You didn’t just interview her. You got in a car with Paula Murphy and she drove with that lead foot. What was that like?

It was amazing. I climbed in the backseat. We were doing an interview. She was in the front seat and the first thing she did was hit the accelerator and do a burnout in the parking lot and never lifted her foot off the accelerator.

I don’t think she drove under 80 [miles per hour] the whole time. Probably closer to 100. She still loved her speed and could still handle the car.

She doesn’t strike me as someone who ever liked sitting on the sidelines.

That is for sure. I think if she could have figured out a way to race when I was with her in that car, she would have. She did not like the sidelines. I think that was probably the hardest part, when the opportunity started to dry up later in life.

I think once those days started kind of dwindling, that’s when people forgot and that’s when she wasn’t in the papers and she wasn’t setting records and she wasn’t on TV shows. And I think that that’s sort of how people kind of forgot that she bridged that gap and led to Janet Guthrie and Danica Patrick and the future of women in motorsports. And that’s a shame.