This article is an on-site version of our Britain after Brexit newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every week

Good afternoon. Two pieces of news in Brexitland this week — one, long in coming, is the UK and the EU belatedly reaching a deal over taking up associate membership of the €95.5bn Horizon Europe science programme.

And somewhat less momentously, but sound the bugles all the same, my short book trying to explain What Went Wrong with Brexit (and what we can do about it) is hitting the shelves at a bookstore near you from today.

Pieties aside, the aim of the book is to argue for a better quality of conversation about the UK’s actual options outside the EU, rather than litigating old arguments that are getting us nowhere.

Today’s Horizon deal has been, rightly, warmly welcomed across industry and academia but it is a grisly reminder of the time, money and effort that’s been wasted these past few years by a succession of British governments.

The UK’s associate membership of Horizon was actually negotiated in 2020, but will start three years late because of the diplomatic row over the UK’s refusal to implement the deal it also signed on post-Brexit trade relations for Northern Ireland.

The EU had a role in that — it was too slow to accept that the Irish Sea border could not operate like the Dover-Calais border — but the original sin remains the prioritisation of a clean-break Brexit over the stability of the Union. (Recall that even Edwin Poots wanted a Swiss-style veterinary deal to make it work. And, even now, the Stormont power-sharing executive remains shut.)

The stand-off over Horizon associate membership continuted after the signing of the Windsor framework deal in February and is illustrative of the grinding reality of EU-UK relations post-Brexit.

It took seven months to negotiate and when the details emerged this morning, the UK was able to claim what amounted to a micro-win: the “clawback mechanism” (which I explored here) has become automatic, rather than discretionary. So now, if the UK gets less cash out than it has put in, then once the deficit hits 16 per cent it will get a rebate without having to petition the Partnership Council that runs the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement.

Moreover, the UK will not start paying contributions until January 2024, which saves the Treasury around €800mn. Also, the UK will not now join Euratom, so it can pursue a different programme on nuclear fusion, which is a concession from the EU side.

But the bald fact remains that the UK has expended a lot of diplomatic effort to end up in a worse place than it would have been as a member — when the UK was in the EU it extracted more from Horizon than it contributed — and all at the cost of three years of lost networking for UK science and industry. Let’s hope the scientific establishment can make up for lost time.

A new pragmatism

This is not to be churlish. Credit where it is due. Rishi Sunak faced down hardline Brexiters in his party and landed the Windsor framework and his government has since inexorably succumbed to the gravitational realities of being outside the EU: rowing back on plans to scrap all EU law by the end of the year; recognising the CE conformity assessment mark and now, after a brief holdout, rejoining Horizon.

As my colleague Janan Ganesh observed in his column this week they are welcome signs of a new pragmatism after the chaotic Johnson and Truss governments. The experience of those chaotic years, he writes, has inoculated the electorate against “grand visions, easy answers, personality-led demagoguery”.

This is true as far as it goes, but the risk is that the new pragmatism now espoused by both Tory and Labour politicians continues to mask the ongoing realities and costs of Brexit, reducing the impetus needed to fix them.

So despite the Horizon deal, the reality is that the UK is now a more costly and bureaucratic place to do science collaboration than it was pre-Brexit.

The UK may have recognised the EU’s CE mark to help business, but the reality is that UK manufacturers who want to engage in EU supply chains remain at a constant, marginal disadvantage. Crudely, it’s still going to be less hassle to deal with Pedro in Barcelona than Peter in Brighton, and over time that is going to be increasingly the case.

Brexit 2.0

The current deal creates a divergence ratchet: the advent of evolving EU regulation on carbon border taxes, supply chain due diligence and rule changes on VAT on services, alongside new EU biometric border checks — what industry calls “Brexit 2.0” — will continue to provide drag. (The Independent Commission on EU-UK Relations has produced a good report on the challenges facing manufacturing.)

Unless, of course, the UK takes active steps to address those issues — for example linking the EU and UK carbon markets and dynamically aligning on industrial and other regulations, all of which will not be easy and will require political leadership.

This may yet emerge, but these realities, which I try to explain in the book in practical terms, are still very much missing from the wider public conversation on Brexit and — for now at least — the Labour party is equally content to skate over the structural nature of the UK’s Brexit cul-de-sac.

Labour leaders promise to “fix” Boris Johnson’s Brexit deal while sticking to his red lines. They deflect by promising important-sounding measures like doing a “veterinary agreement” or a promise to obtain “mutual recognition of professional qualifications” — but those promises don’t amount to fixing Brexit.

A deal on mutual recognition of professional qualifications is possible under the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement, but it’s worth recalling that Canada has a similar provision in its trade deal with the EU but it took nine rounds of negotiations and over a year to get a single side-agreement on architects.

While those things will be useful for individual industries and worth having, the UK will still find itself at a consistent marginal disadvantage as a result of its trade deal with Europe.

So that new pragmatism is seductive, but it’s dangerous if it becomes a distraction from confronting the actual challenges of making the UK an attractive investment proposition outside the EU single market.

As Jonathan Portes points out in his review of my book in the Guardian, the UK’s productivity and investment woes predate Brexit. While fixing Brexit isn’t a panacea for all the UK’s economic ills, I’d argue facing up to the realities of the UK’s exit from the EU is an important gateway to confronting wider domestic challenges facing the UK — on planning, Whitehall delivery, skills and city densification.

We’re still a long way from anyone making the emotional case for Europe, something the historian Dominic Sandbrook calls for in his review for The Sunday Times, but the polls suggest the majority of the public have moved beyond the simplistic need for British “assertiveness” that Daniel Hannan still thinks will do the trick, according to his predictably furious review in the Telegraph.

Given the divisiveness of the old Brexit debate, I understand the attractiveness of the “anything for a quiet life” strategy, but if a new government actually wants to make a difference, it may need to be braver than that.

Brexit in numbers

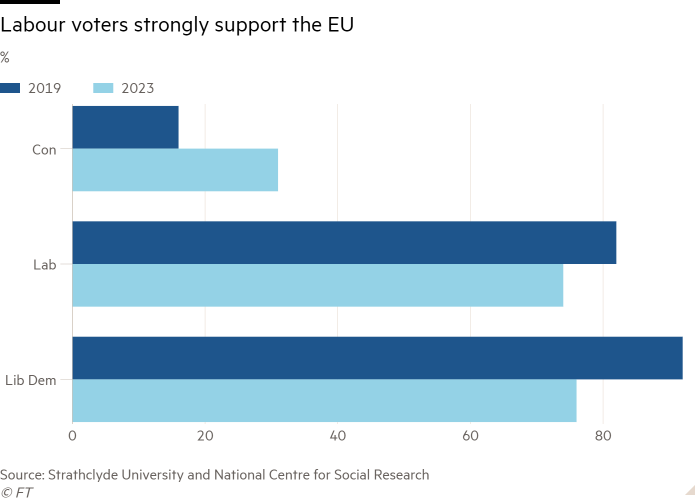

This week’s chart comes courtesy of polling maestro Sir John Curtice, who I heard on the radio the other day making the point that if Sir Keir Starmer wins power, he’ll have an electorate and party that’s overwhelmingly (over 70 per cent) pro rejoining the EU.

That doesn’t mean that the UK will suddenly rejoin, of course, but it does point to a gap between Labour voters’ instincts on Europe and the Labour party’s currently limited and defensive messaging on fixing the challenges raised by Brexit.

Being a policy reporter, not a Westminster type, I’m always struck by the apparent unanimity of agreement among political columnists and politicians that Starmer’s reticence is smart and necessary politics needed to win back the ‘Red Wall’ seats that went Tory in 2019.

But chatting to Curtice it feels much less clear why that is the case. He identifies what he calls a “mismatch” between Labour’s position on Brexit and the actual character of the Labour electorate, including in the Red Wall, where Labour voters are still majority ‘remain’.

Given that Brexit is now “10 points less popular” than it was in 2016, Curtice argues that the assumptions behind Labour’s tentativeness on Brexit are “largely out of date” and that — given the 18-point lead Labour enjoys in the polls — the ‘Red Wall’ is going to “collapse mightily” anyway.

He also makes the point that Labour’s current poll lead is not founded on its canny reticence over Brexit, but because of the electorate’s general recoil from the Tories driven by partygate and the debacle of Liz Truss’s “Kamikwasi” budget.

“I’m at least raising question marks on the extent to which the foundation of Labour success has been in attracting leave voters,” he adds. “We can still argue about the risks of Labour talking about Brexit — it’s not obviously to their advantage — but it does mean that Labour does have to realise it will find itself back in office off the back of an electorate that is three-to-one in favour of joining the EU.”

Britain after Brexit is edited by Gordon Smith. Premium subscribers can sign up here to have it delivered straight to their inbox every Thursday afternoon. Or you can take out a Premium subscription here. Read earlier editions of the newsletter here.

Recommended newsletters for you

Inside Politics — Follow what you need to know in UK politics. Sign up here

Trade Secrets — A must-read on the changing face of international trade and globalisation. Sign up here