Receive free Geopolitics updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest Geopolitics news every morning.

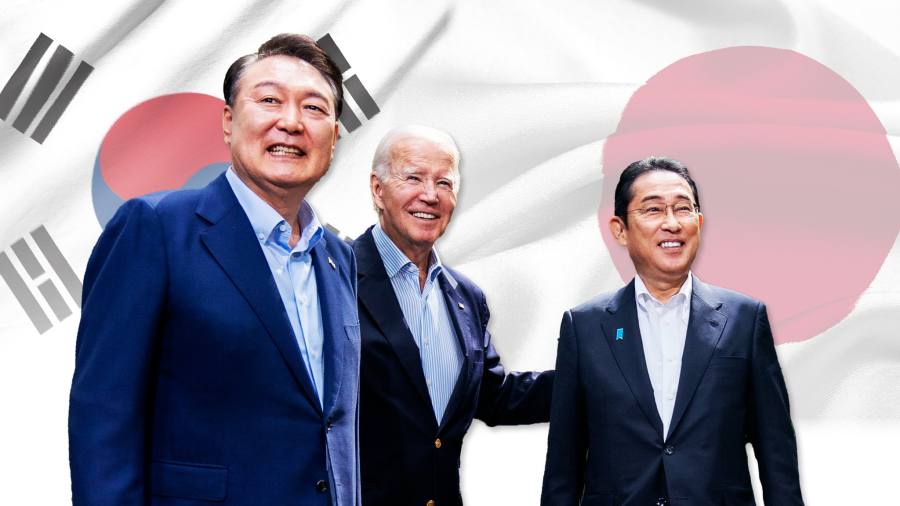

For former US officials who recall years of gruelling diplomacy when Seoul and Tokyo were scarcely on speaking terms, last month’s Camp David summit must have felt like a minor miracle.

US president Joe Biden had managed to bring together Fumio Kishida of Japan and South Korean president Yoon Suk Yeol in one place, seemingly as allies. But whether the summit will prove as “historic” as the leaders claimed is open to question.

Biden pocketed a series of impressive gains in his campaign to bind Asian partners into his regional security agenda. But many of the initiatives it produced build only very modestly on past practices. Others simply offer new channels for discussion that may or may not yield meaningful results.

Aside from the prospect of a second Trump presidency, there is a further compelling reason for caution: the diplomatic rapprochement sealed by South Korea and Japan this year is far shakier than it looks.

“The idea that Camp David was the moment Japan and South Korea moved past their historical issues is a dangerous illusion,” said Daniel Sneider, a lecturer in east Asian studies at Stanford University.

For decades relations between the two countries have been dogged by controversies relating to Japan’s occupation of the Korean peninsula in the first half of the 20th century.

At the political level, the tides of co-operation have ebbed and flowed as the South Korean presidency passes back and forth between conservatives who have traditionally pursued a conciliatory line towards Tokyo and leftwingers rooted in a nationalist tradition that remains deeply sceptical of Japan’s intentions.

In 2018, relations collapsed after South Korea’s supreme court ordered two Japanese companies to pay Korean victims of Japanese wartime forced-labour practices.

Moon Jae-in, Yoon’s leftwing predecessor, promised not to intervene in the court cases, limiting diplomatic routes for resolving the dispute, while Tokyo insisted all claims related to its colonial occupation of the Korean peninsula were resolved by a 1965 treaty. The result was a five-year stand-off during which almost all co-operation ground to a halt.

After Yoon, a conservative former prosecutor, was elected last year, his administration sought to break the impasse by proposing that Japanese and South Korean companies pay into a private fund that could be used to compensate the forced-labour victims.

The proposal was sensible, but the talks failed after the Japanese government refused to allow its companies to pay into the joint fund. Instead South Korean companies alone would pay into the victims’ fund, while companies from both countries would pay ¥200mn ($1.4mn) into a pair of “future partnership” funds to collaborate in areas including youth exchanges, energy security and global supply chain issues.

Tokyo’s refusal to give an inch on Yoon’s proposal dismayed many South Koreans, including many beyond the old Japan-baiting left. But Yoon declared the issue resolved regardless, paving the way for a visit to Tokyo in March for the two countries’ first bilateral summit in 12 years.

For supporters in South Korea and the US, Yoon’s decision to brush aside the forced-labour issue served as a demonstration of vision and courage. But domestic critics accused him of having sold victims down the river. Opposition leader Lee Jae-myung, whom Yoon defeated by a margin of less than 1 per cent in last year’s election, has described Yoon’s meeting with Kishida in March as “the most shameful and disastrous moment in our country’s diplomatic history”.

Much of South Korea’s left also opposes the country’s wider alignment with the US and Japan in opposition to the burgeoning axis of Moscow, Pyongyang and Beijing. “There is no reason for us to be antagonistic against China and Russia,” Moon Chung-in, a former senior adviser to President Moon, told the Financial Times.

Even observers who want to see Yoon’s efforts succeed wonder if the unpopular gambit of an unpopular leader provides a sure enough foundation for lasting amity, a concern shared by Japanese officials.

Noting South Korean anxieties over the recent release of radioactive water from the Fukushima nuclear plant, Tokyo is hesitating to commit to concrete bilateral and trilateral initiatives ahead of South Korea’s parliamentary elections next year.

But Sneider said if Japan really wanted the rapprochement to succeed, Kishida needed to offer the South Korean people a gesture of genuine compassion that went beyond the stale legal arguments and rigid formulations of regret upon which the Japanese leader continues to rely.

“My worry is if this all collapses, the Japanese will say: ‘We told you so, the Koreans are not reliable partners,’” said Sneider. “But on this occasion, it would be Japan’s fault.”