For the past few years, David Keeler’s addiction has been treated like a medical issue.

“I’ve worked out [that] I can wake up in the morning without using, come to work until 5 o’clock at night and only use [drugs] once in the day when I get home,” said Keeler, an outreach worker at SOLID, a peer-based harm reduction organization in Victoria.

“That is due to the fact that I am a patient of the Safer Initiative, so I get doctor-prescribed fentanyl.”

He is one of a few dozen people in Victoria who has access, via a doctor’s referral, to a Health Canada-funded program that provides what’s known as safer supply, or pharmaceutical alternatives to the increasingly toxic street drug supply. Keeler said another safeguard is going to known suppliers and always getting substances checked at a drug-checking facility.

According to Keeler, and researchers in B.C. and Ontario who monitor illicit substances sold on the street by testing anonymous samples, trends have indicated that substances now have stronger concentrations of potent combinations, from fentanyl to animal sedatives, that create a more volatile and dangerous situation for people who use drugs.

In B.C., the coroners service reports that the first seven months of 2023 have been the deadliest since 2016, when the province declared a public health emergency over drug poisoning deaths.

More than 7,300 people died across Canada last year, most of whom were in B.C., Alberta, and Ontario. First Nations people in B.C. died at nearly six times the rate of other residents last year, according to data from the First Nations Health Authority in B.C.

With the toxic drug supply continuing to claim thousands of lives across Canada every year, experts, advocates, and drug users are drawing attention to a growing demand for harm-reduction services — like drug checking and doctor-prescribed substances, called safer supply — that are currently only available in a select few communities.

This International Overdose Awareness Day, there are 123 events and marches across Canada — and hundreds more worldwide — to commemorate the lives lost and call for action.

More demand for drug checking

Bruce Wallace, a professor at the University of Victoria and co-lead of the university’s drug checking project, and Hayley Thompson, manager of Toronto’s drug check program run out of St. Michael’s Hospital, found the toxicity of substances on the street were further exacerbated during pandemic-induced lockdowns.

“We started to see that there are often what we would call multiple actives,” Wallace said. “Most opioids were then combined with some other drugs.”

These include high potency benzodiazepines, fentanyl analogues like fluorofentanyl, and in smaller quantities, xylazine, an animal sedative that has been detected in recent years across North America’s drug supply.

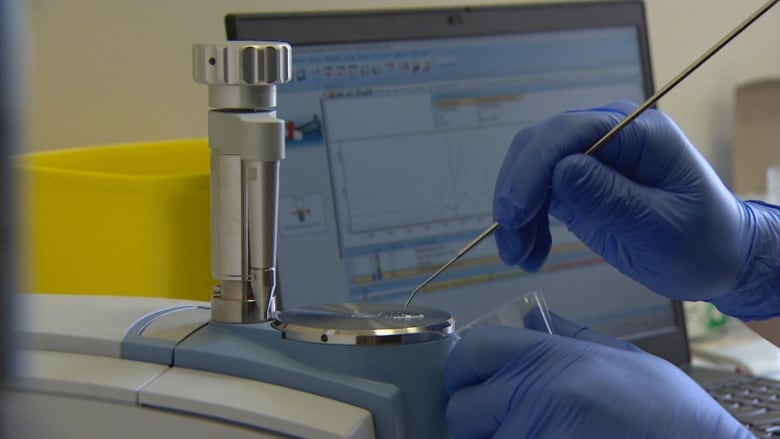

According to Wallace and Thompson, drug checking in B.C. is more prevalent than elsewhere in Canada. The province has 25 Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectrometers for drug checking, with several in each health authority. Other provinces have had this service either in their largest municipalities or not at all.

“We’ve actually been the only drug-checking service in the province [of Ontario] up until this year,” Thompson said.

“There’s [now] one in Thunder Bay and there’s one in Peterborough and we know there are a number of other municipalities that are getting them up and running, but they’re not receiving funding from the Ontario government to do so. They’re doing it independently.”

In 2016, when the public health crisis was declared by the province, it was never an expectation that we’d still be in the same spot so many years later.– Bruce Wallace, University of Victoria

Wallace thinks the declaration of a public health emergency has been helpful for drug checking in B.C., as well as prompted regular data gathering and other harm-reduction measures in the province.

“It would have been harder for us to be able to implement things like overdose prevention sites and decriminalization and drug checking without the declaration, I believe,” said Wallace, who is also a scientist with the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research.

A first-of-its kind drug checking site opened in Edmonton allowing users to have their substances tested before they are consumed. Technicians can test a range of drugs for toxic substances and levels. Once the drugs are tested, users are alerted to the contents in person, by phone or email.

Toronto has a Health Canada-funded program that operates out of five supervised consumption sites, and local initiatives exist in Alberta, Saskatchewan, Yukon, Quebec, and Prince Edward Island.

“The demand for our service is definitely increasing,” said Thompson. “We get calls from people or organizations all over the province and country, who are like, ‘How do I get this in my community?'”

In the past year, the Victoria drug-checking project has developed a new method to reach smaller communities in central Vancouver Island; so far in 2023, this region has had the second highest rate of drug poisoning deaths in B.C. after Vancouver, according to B.C. Coroners Service data.

The method, which Thompson says is ahead of the game while Ontario facilities await long-term funding, involves training front-line workers in smaller central Vancouver Island communities to collect drug samples, usually at an overdose prevention site, and sending them to a technician in Victoria for analysis.

It uses new technology developed by the UVic drug checking project and eliminates the need for a skilled technician in a rural community, but the turnaround time can be a couple of days, versus 20 minutes in Victoria.

Few have access

Drug checking and collecting data about drug-poisoning deaths, like B.C. does, is an important step to help drug users make an informed decision about their consumption, experts said, but is not enough on its own.

“We have more data in B.C. and more routine reporting of everything but to continually report how bad the situation is obviously doesn’t respond to the situation,” Wallace said.

“In 2016, when the public health crisis was declared by the province, it was never an expectation that we’d still be in the same spot so many years later.”

The death rate has more than doubled since the public health emergency declaration 2016, and now stands at 42 per 100,000 in B.C — making unregulated drugs the leading cause of death in B.C. for people aged 10 to 59, according to the B.C. Coroners Service.

“Despite recommendations for the urgent expansion of a safer drug supply, very few have access to a stable, lower-risk alternative,” said the province’s chief coroner, Lisa Lapointe, in a statement on Aug. 29.

B.C. reports that in June 2023, 4,619 people were prescribed safer supply opioid medications.

But experts say these and other harm reduction measures are not available on wide enough scales to have a more tangible impact.

“We learned through the decades of [data from] supervised injection sites like Insite, [that] having a dozen booths to serve a whole health authority was really a limited response,” Wallace said. “You just can’t expect that to really reach the range of people and I think we also have that challenge with drug checking.”

In Vancouver, advocates and health officials have decried the city’s decision to not renew the lease of an overdose prevention site in downtown, meaning the facility has until March 2024 to find a new location.

Overdose consumption sites in Ontario are undergoing a critical incident review after a woman was killed in a shooting outside the South Riverdale Community Health Centre in Toronto in July.

“It’s a much different political landscape [in Ontario],” Thompson said. “Also the number of consumption treatment services in Ontario was capped by the Ford government a number of years ago.”

The province’s revised strategy under Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservative government in 2018 limited the number of supervised consumption sites allowed in Ontario to 21.

The majority of opioid overdose deaths in Canada — as much as two-thirds in some provinces — are now caused by smoking drugs, but government red tape is slowing efforts to save lives. The CBC’s Jonathon Gatehouse explores why it’s so difficult to get safe smoking sites approved.

Supply and demand

It’s difficult for either Thompson or Wallace to say for sure why the drug supply is getting more dangerous, but they have several theories.

One, Thompson said, is that xylazine has been introduced into the drug supply as an alternative to benzodiazepines due to ease of access — it is used in veterinary care and is therefore readily available.

“There’s also this theory of the ‘Iron Law of prohibition,’ which is that as more measures are put in place to try and crack down on the unregulated drugs supply, whether that’s the scheduling of drugs, so making them harder to import, or whether it’s police intervention to cut drugs out of the supply…new drugs will continue to pop up when that happens,” Thompson said. “And often, they will be more potent in an effort to try and evade detection.”

The current mix of substances means those who rely on street drugs have developed multiple addictions, said Keeler. Through his outreach work, he says he has heard people are having more trouble accessing prescribed safer supply these days.

“I’m seeing that people are getting cut off of safe supply more than getting put back on it,” Keeler said, adding his belief that doctors are unwilling to prescribe the large doses needed for people in active addiction. “I think [governments] need to put money towards practicums for nurses to walk around with us … so that they’re able to to understand how to better help with the fentanyl crisis.”

According to Thompson and Wallace, compassion clubs like the Drug Users Liberation Front in Vancouver — through which people who use drugs purchase substances in large quantities, have it checked, and then disseminate them — are another grassroots-level initiative created to save lives during the toxic drug crisis.

But due to the level of personal risk, political landscapes, and availability of street substances that are in demand, compassion clubs are not considered a scalable solution at the moment.

“A lot of these responses can be useful but they’re limited and they’re not having a meaningful impact unless they can be really scaled up and reach the overall population of people who are using drugs and at risk of overdose,” Wallace said.