Steven Kelly is associate director of research at the Yale Program on Financial Stability and publishes research notes at his Substack, Without Warning.

As a financial crisis starts receding from view, so begins the time-consuming analysis of 10Ks and 10Qs to determine the cause.

But crises happen in 8Ks — the normally innocuous ad hoc filings that also accompany company emergencies — not 10Ks. Ex post analysis too often ignores the way markets assessed and triggered a crisis in real time, and instead finds a way to back into the answer in Excel. The 2023 bank crisis really began when Silicon Valley Bank filed an 8K on March 8 suggesting its business was less viable than hoped at this point in the macroeconomic cycle.

Recently, however, Vice Chair for Supervision Michael Barr included the 2023 bank crisis among his justifications for a marginal planned increase in bank capital ratios. Elsewhere in these pink pages, columnist extraordinaire Rob Armstrong has taken exception to Barr’s connection of capital requirements to the bank crisis of 2023. After dutifully considering the counterarguments, Armstrong says, “There may be good arguments that show that all banks need more capital. The SVB mess is not one of them.”

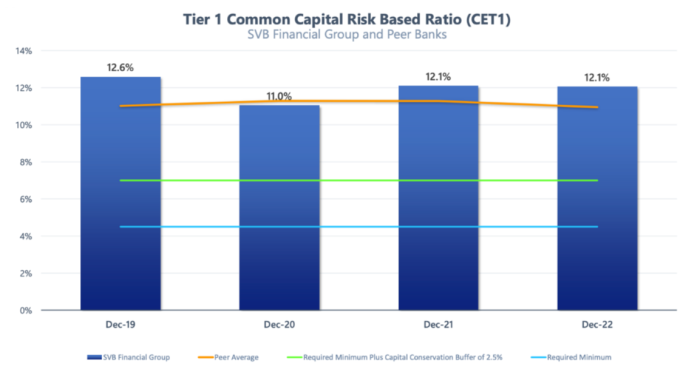

SVB’s failure certainly wasn’t about the measured level of regulatory capital. Even its CEO shared how robust SVB’s capital was in his postmortem for Congress:

It’s indeed tough to look at SVB’s regulatory capital and conclude that the problem would have been prevented by Fed Vice Chair for Supervision Barr’s plan to raise capital ratios by two percentage points. Same goes for Signature and First Republic. (Oh, and UBS’s and Credit Suisse’s capital ratios were nearly identical . . . )

Moreover, even on a mark-to-market capital basis — adjusting bank capital for those massive unrealised losses SVB and others revealed in their 10Ks and 10Qs — it’s not as if March revealed new information about that regularly reported balance sheet adjustment. SVB had reported massive unrealised losses relative to capital for several quarters; indeed, their losses were declining in their final financial report before failure. First Republic similarly had long reported unrealised losses. Meanwhile, Signature Bank, which failed the same week as SVB, had only nominal unrealised losses. All these banks’ share prices rightfully lagged the broader banking sector in 2022.

Even so, the capital purists are still right that more capital would’ve saved these banks. That’s just a tautology, as capital represents distance from bankruptcy. But the amount of capital these banks’ business models would’ve needed to avoid failure was asinine — maybe to the point where it’d be hard to call them banks. (Definitionally, you can’t have an all-capital-funded bank. Banks exist to create deposits.) A robust assessment of these banks’ viability across macroeconomic environments would have called for much earlier capital increases, irrespective of the unrealised losses at some of them. It was these particular banks — who bet their franchises on economic froth — that couldn’t raise capital when they ultimately needed it.

While all the banks above could have benefited from more capital in hindsight, it’s not because of their unrealised losses. If it were, that would imply that we should make Bank of America raise over $100 billion in capital right now to clean up its duration losses, which seems . . . extreme, to say the least.

Imagine a hypothetical where those much-discussed BofA unrealised losses were similarly the size of its total capital, but everything else about its business was the same. (The total unrealised loss amount is indeed near BofA’s current level of tangible common equity.) Would BofA have any trouble raising new equity? Of course not. It might be expensive and dilutive, but certainly someone like Warren Buffett would be happy to get such a deal on a great franchise like BofA. The bank has a strong business model — even with the current tight monetary policy and the recent turn of the tech cycle — and a strong base of deposits that aren’t in accelerated run-off mode.

Schwab is another example. In fact, the unrealised losses at Schwab are several billion dollars larger than its tangible common equity. Yet, after an initial repricing from about $80 to about $50, its stock has been trading sideways and slightly upward at around $60. Turns out being America’s favourite brokerage and minting new customers while also having an attached bank that’s nursing unrealised losses is still a valuable aggregate proposition on a go-forward basis. As the WSJ reported of one institutional investor (with our emphasis):

Michael Cuggino, president of the Permanent Portfolio Family of Funds, which owns Schwab shares, thinks the banking crisis could be over — and if it isn’t, he figures Schwab’s earnings can be cushioned by its other businesses, including its services to financial advisers and asset management. His firm added to its Schwab holdings in March.

Moreover, the WSJ also wrote a whole story about Amalgamated Bank, which has (1) unrealised losses that account for all its equity and (2) a high share of uninsured deposits, where . . . nothing happened. That’s because, as a banker to non-profits and unions, it’s not facing the macroeconomic risk that banking for tech and crypto is. There was no reason to run on the business model. (The bank, for its part, just thinks it has the mostest loyalest of loyal depositors.)

It is rather worrying how quickly the macroeconomic establishment is settling on various forms of the narrative of “in March 2023, depositors saw large unrealised losses relative to capital at their bank and got spooked, sparking a run.” Importantly, what sparked the run in real time wasn’t low capitalisation to assets, adjusted or otherwise.

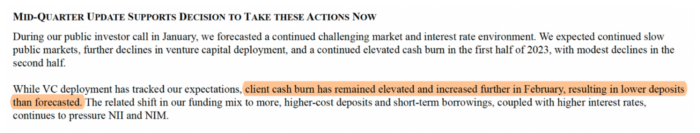

Rather, it was the accelerated cash burn (ie natural deposit run-off) in the start-up/VC/tech communities where it did the vast majority of its business. When it shared that information privately with potential equity investors, it only raised a fraction of the equity it was looking to raise.

Its crisis 8K came on March 8, when it made that information public. That filing told the story of an innovation economy drawing down its liquidity and seeing inflows dry up at this point in the macroeconomic cycle — and that private-equity investors would take an equity stake in SVB only if the bank completed its public-market equity offering.

Regulatory ratios measure capital to assets, and financial statement accounting makes some adjustments. But the market measures capital relative to a business model.

You can have the most loyal depositors in the world, but that can’t stop them from running down their deposit balances for macroeconomic reasons. This revelation also sparked parallel runs on businesses that looked like SVB — banks that bet the franchise on the likes of tech/crypto/etc—ultimately felling Signature and First Republic.

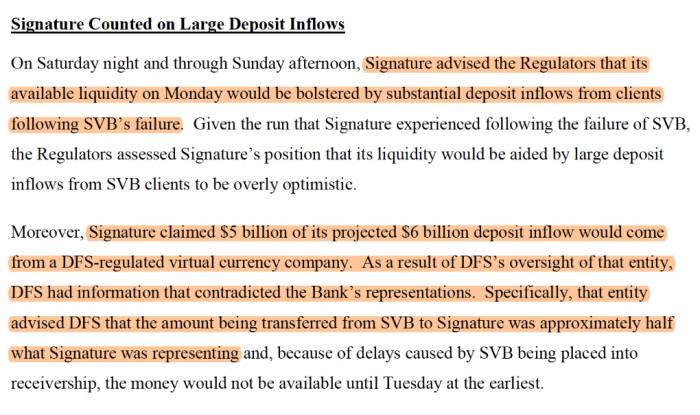

First Republic shared similar clientele to SVB, and its run started on the second day of SVB’s. On the first day, it saw inflows, suggesting that SVB customers already had accounts there. By Day 2, the money moved on to pastures that were, well, greener. Signature had bet too much of its franchise on catering to crypto — which was likely facing even faster deposit attrition than the tech start-up community. Signature also had client overlap with SVB; indeed, the New York Department of Financial Services reported that Signature was expecting client inflows if allowed to open that Monday morning. The NYDFS shared one specific example where it knew better than Signature — to the tune of a few billion dollars (with our emphasis):

Other West Coast banks with material focus on the tech and VC — such as PacWest and Western Alliance — similarly came under pressure but ultimately survived. The list of banks that looked vulnerable did not change from the initial run in March, and contagion never spread to Wall Street. This was a run on a business model of some banks, not on the banking business model.

A bank that can’t raise capital had better look good from a liquidation perspective — which is not easy for a bank, a leveraged business where value is tied up in the interaction of its staff, assets, counterparties, credit rating, and stock price. Look at the expected losses that the FDIC took on from Signature Bank ($2.4 billion) or the size of the bail-in at Credit Suisse ($17 billion). Neither of those banks were sitting on mark-to-market rate losses.

Even for a bank with clear positive value in liquidation, there’s not much incentive to remain a customer. It’s not as if it makes much sense to build a relationship with a bank that doesn’t look like it’ll be in business for long. Case-in-point was the reopened SVB, FDIC-bridge-bank version. It was promoting its then-unlimited FDIC deposit insurance.

Yet, instead of attracting every uninsured deposit in America at that fragile time, neoSVB continued to bleed customers. It’s not as if a bridge bank was going to give clients that credit line expansion they were hoping to get next year, and it may even freeze their existing ones. Best to start building a relationship elsewhere — whether you’re depositor or employee — as soon as possible. And not at a bank that looks like the one that just gave you a scare. That includes First Republic, Signature, etc . . . or even First Citizens (awkward).

In other words, the point isn’t necessarily a bank’s capital ratio. Instead, it’s whether its business is equitisable. An inability to equitise ultimately took down SVB and a handful of its peers.

Credit Suisse’s foundering share price — that is, its low equity-market capital levels — left it in slow failure mode for a while. That lasted until its capital provider of last resort went on the news and said “absolutely not” to injecting more capital, seemingly accidentally pulling the plug. Or, as the Swiss National Bank put it: “The announcement by a major shareholder that it would not recapitalise the bank was probably the ultimate trigger of a massive loss of confidence.” (This all probably has implications for the uninsured deposit insurance reform debate: Equity markets did lots of bank disciplining, telling us which banks needed to be closed.)

Banking is a balance-sheet business. You don’t have to be profitable now, but you need a strong business model so someone is willing to provide equity — whether directly or via ongoing earnings from customers and counterparties. The very presence of a capital provider of last resort can often pre-empt a need for that last-resort capital and encourage customers/counterparties to keep conducting business. But sometimes, amid significant macroeconomic uncertainty, banks need to prove themselves to the market. The ability to raise/generate capital is what keeps a bank in the business of banking. Otherwise its options are failure, or needing to raise so much capital that it no longer resembles a bank.

These banks weren’t felled by interest-rate risk in the traditional sense. That risk is easily tracked through 10Ks and 10Qs and affects many surviving banks.

The banks failed because they built deposit franchises on sectors vulnerable to burning through deposits when higher rates took some air out of the economy. Tech equities, crypto, VC, start-ups: these are the most junior tranche of the economy. And these banks tied the fate of their most senior liabilities to that junior tranche’s performance. SVB’s March 8 revelation of accelerated cash burn and limited private capital raise was the bellwether of a business model that had rotted.

*It could be argued that there were unrecognised unrealised losses on Signature’s balance sheet given the FDIC’s loss-on-sale of Signature assets. However, those losses would — as with the other banks — not be new, nor were they the real-time focus of investors that weekend who saw Signature instead as a crypto bank. Moreover, the loss-on-sale could just signal the costs of uncertainty and handing over a portfolio of unique assets — from a bank known for high-touch service — to a different set of managers. Indeed, the postmortems on Signature conducted by the FDIC and the New York Department of Financial Services make no mention of unrealised losses.