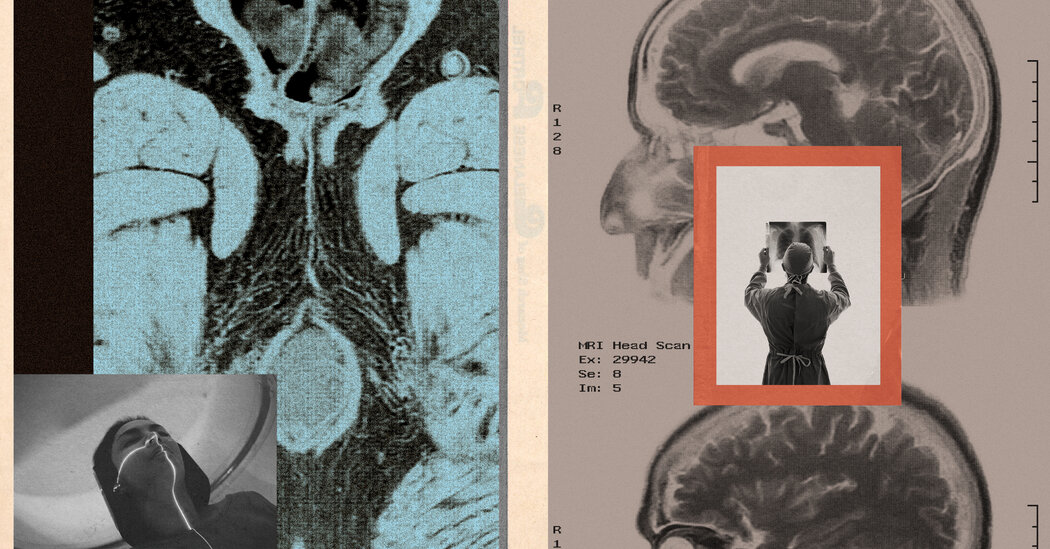

From my CT scan, I expected a brush with mortality — the opportunity to see the forbidden land of my own guts, to contemplate their eventual decomposition. By that point I had already had an organ removed (my gallbladder), and I suppose I expected to register its absence somehow. What I saw instead was just shades of gray and blobs of darkness. Nothing was recognizable as an organ. At one point, I remember, the doctor directed me to pay attention to something that, in his own words, did not look like anything at all. That, he wanted me to know, was my pancreas. He was right: It did not look like anything at all. If, for Anna Röntgen and Hans Castorp, the X-ray produced something that was undeniably and terrifyingly their own body, I was having the opposite experience. Whose body was this? Was it a body at all? Without the doctor there to tell me what it was I saw, I would never have known.

In popular culture, medical imaging represents a simple statement of fact, a question resolving into certainty. Watch episodes of the medical drama “House, M.D.,” and you will see imaging confidently used to diagnose psychopathy, to tell whether somebody is lying, even to visualize the subconscious. People lie and bodies deceive, but tests and scans do not. And so, in the real world, one submits to these devices nervously, as one would to some kind of truth serum or all-seeing eye: There is no hiding here.

Even when we imagine a superhero with X-ray vision, we imagine somebody who sees through the inessential to the essential. In a scene in the 1978 “Superman,” the Man of Steel flirts with Lois Lane first by scolding her for smoking, then by scanning her for lung cancer. (Her lungs glow pinkly and cutely for a moment before he informs her that she’s all clear. Later, at her request, he tells her the color of her underwear.) Like his superstrength, Superman’s X-ray vision is allied to his virtuous nature: His eyes tell the truth and can’t be fooled.

Nobody expects strict medical accuracy from superhero movies. But popular science narratives are hardly more cautious. We are often breathlessly informed, for instance, that parts of the brain “light up” when presented with certain stimuli, telling us precisely what people are thinking and feeling and why. (Of course, parts of the brain do not light up at all — only their images on an f.M.R.I., indicating blood flow.) Even in everyday life, medical images convey an official certainty that’s hard to obtain through other means. I’ve known friends to forgo different parts of the medical process throughout pregnancies, but the pregnancy-announcing sonogram is de rigueur. Without that image to show friends, you simply aren’t pregnant, socially speaking; you just might be.

For medical professionals, though, all these imaging techniques are imperfect tools, just another way to get a partial idea of what might be happening inside a human body. You have to be trained to read them at all. The doctors on “House” run and pore over scans themselves, but in reality both creating and interpreting CT scans are specialized jobs. Radiology can be subjective — not as subjective as, say, art criticism, but not cut and dried. In the future, artificial intelligence may take a greater role in interpreting results — but it will not make the experience any less alienating if, instead of depending on human expertise to analyze your body, a computer program is making judgments and flagging risks based on patterns and correlations even the doctors may not be able to see.