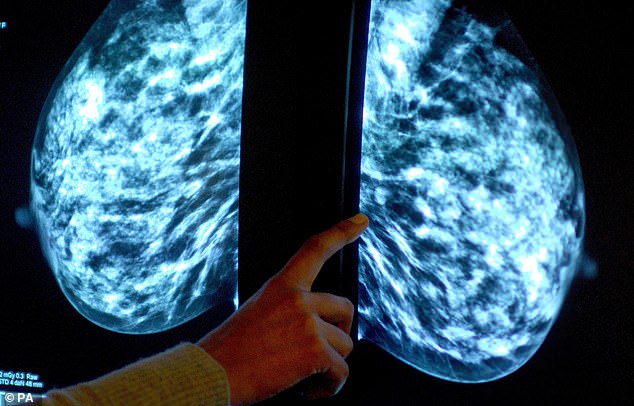

Using AI for breast screening detects 20 per cent more cancers and halves the work of radiographers, a major study found.

The first research to trial AI in a national breast cancer screening programme found it has the potential to make it more accurate and efficient.

Research involving more than 80,000 women revealed AI-supported screening detected a fifth more cancers compared with the routine, double reading of mammograms by two radiologists.

Crucially, it did not increase false positives – when a mammogram is incorrectly diagnosed as abnormal.

Experts stress further trials are needed but suggest the technology could become an essential tool in future screening, increasing detection while also boosting capacity.

The first research to trial AI in a national breast cancer screening programme found it has the potential to make it more accurate and efficient

Researchers studied screening results involving 80,033 women from Sweden between April 2021 and July 2022.

Half had standard care which involved their results being assessed by two radiologists, while the other half were assessed by AI followed by at least one radiologist.

In total, 244 women from AI-supported screening were found to have cancer compared with 203 women recalled from standard screening.

The proportion of false positives was 1.5 per cent in both the AI group and the group assessed by radiologists.

With a shortage of radiologist on the NHS and more widely, the findings suggest AI could ease the workload.

There were 36,886 fewer screen readings by radiologists in the AI-supported group – a 44 per cent fall – according to the results published in the Lancet.

Dr Kristina Lång from Lund University, Sweden, who led the study said it had the potential to cut radiographer readings by half.

She said: ‘The greatest potential of AI right now is that it could allow radiologists to be less burdened by the excessive amount of reading.

‘While our AI-supported screening system requires at least one radiologist in charge of detection, it could potentially do away with the need for double reading of the majority of mammograms easing the pressure on workloads and enabling radiologists to focus on more advanced diagnostics while shortening waiting times for patients.’

Final trial results looking at whether AI can improve cancers detected between screenings, which tend to have a poorer prognosis, are expected in several years.

Experts hailed the results as ‘exciting’ and suggested, when combined with experienced specialists, will be ‘a formidable force in patient care.’

Dr Katharine Halliday, president of the Royal College of Radiologists, said: ‘AI holds huge promise and could save clinicians time by maximising our efficiency, supporting our decision-making and helping identify and prioritise the most urgent cases.

She added: ‘Whilst real-life clinical radiologists are essential and irreplaceable, a clinical radiologist with the data, insight and accuracy of AI will increasingly be a formidable force in patient care.’

Dr Kotryna Temcinaite, head of research communications at Breast Cancer Now, said: ‘We look forward to the final results of this exciting Swedish trial to understand if AI can help improve breast cancer screening and increase capacity in the future.

‘But there are urgent issues in the breast screening programme in the UK that must be addressed now, including outdated IT systems which take up valuable staff time and delay improvements.

‘That’s why Breast Cancer Now has launched a transformation blueprint which sets out the steps the programme in England must take to ensure it’s ready to make the most of new innovations, like AI, in the years to come.’

Source