This article is part of FT Globetrotter’s guide to Zürich

There are few sweeter places on earth than the Sprüngli tea room on the Paradeplatz in Zürich. People come, people go, perfect confections are consumed, and nothing ever happens. One-hundred and sixty-five years of Swiss stability.

And yet, in 1917, the gutbürgerlich hum of the tea room was disturbed by curious sounds from upstairs. Herr Sprüngli had let the premises above the Confiserie to Han Coray, a dealer in avant-garde art who had, in turn, sublet the space to the Dadaists, a group of radical artists who had taken refuge in Zürich away from the war that was raging across Europe.

Led by Hugo Ball and Tristan Tzara, Galerie Dada exhibited paintings by Kandinsky, Feininger and Klee and staged events in front of spectators sat on multicoloured chairs painted by fellow Dadaist Emmy Hennings (on the opening night the paint had not quite dried, resulting in the audience becoming an “involuntary symphony of colours”). These were soirées characterised by a “frenzy such as Zürich has not seen before”, as Ball put it. For two months, these events continued, but in the end financial constraints and the sound of “very modern music” led to the lease being terminated. Peace was restored to the tea room; rhum Baba prevailed over rum Dada, much as it does today.

As the cultural capital of neutral Switzerland, Zürich has a long tradition of welcoming émigré artists and intellectuals; talent finding kindred spirits and cultured audiences, away from the miseries of revolution, oppression and war. Here are a few favourite émigré haunts.

Dada

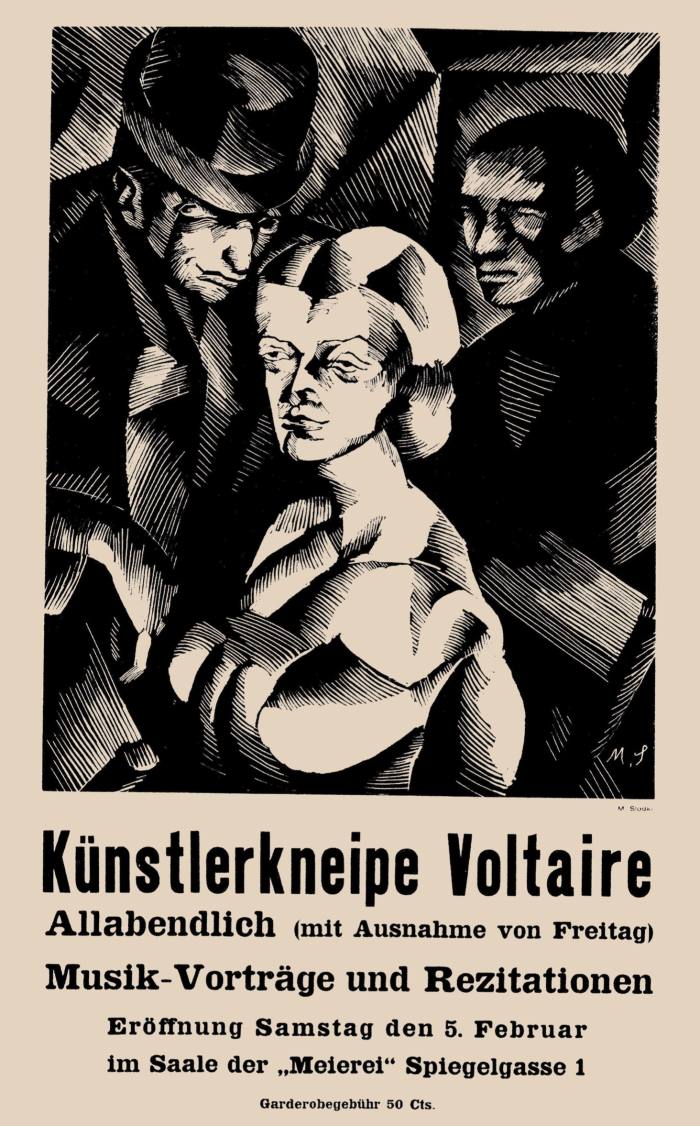

Dada was born at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zürich’s old town on Spiegelgasse. There, for a few months in 1916, a group of émigré and Swiss artists staged evenings of “madness and unconsciousness” — an experimental mix of art forms: visual, poetic, physical and phonetic. The Cabaret was painted black and blue by Jean Arp and hung with works by Marinetti, Modigliani and Picasso, and Marcel Janco designed outlandish Cubist costumes, including a “magic bishop” outfit in which Hugo Ball recited sound poems.

The premises in their current form are a 21st-century revival with an interesting, if tamer, programme of events and a lovely gallery showing Dadaist and contemporary work, with a café-bar frequented by an engagingly arty set. On the wall outside is a beautiful plaque created by Arp in 1966 to mark Dada’s 50th anniversary.

While the Dadaists were effervescing at No 1 Spiegelgasse, a rather gloomier neighbour in the form of Vladimir Ilitch Lenin was plotting at No 14.

After the Cabaret closed in the summer of 1916, the Dadaists used several other premises for their performances. The first of these was the Zunfthaus zur Waag, the patrician mansion of the linen and woolweavers’, hatters’ and bleachers’ guild. Today, the Zunfthaus is a delightful place for lunch and, if you ask nicely, you may be shown the panelled hall where the Dadaists performed.

Berthold Brecht and other writers

With fascism taking over most of the German-speaking world in the second world war, numerous Austrian and German writers came to Zürich. The Schauspielhaus, Zürich’s main theatre, quickly moved from relative insignificance to being the leading free German-language theatre; three of Berthold Brecht’s plays had their first performances there during the war. Eighty years later, the Schauspielhaus remains one of the great stages of the German-speaking world and Brecht a staple on its repertoire.

The basement of the Genossenschafts bookshop (now the wonderful Buchhandlung im Volkhaus, just off Helvetiaplatz), known as “the Catacomb”, became an important literary venue, promoting both émigré authors such as Ignazio Silone, Walter Mehring, Mascha Kaléko and Brecht, and Swiss writers who had lost their overseas markets.

Another centre of literary life was the Museumsgesellschaft library on the Limmatquai, whose reading rooms were frequented by James Joyce, Gottfried Keller, Stefan Zweig and Lenin. Joyce’s and Zweig’s membership cards (together with those of several other illustrious members) are displayed in the staircase. A modest SFr10 will buy you a day pass for the library and a bright and beautiful place to read or write.

Richard Wagner

It seems incongruous that Zürich’s most gilded hotel should be closely associated with a 35-year-old revolutionary who had been forced to flee Dresden after helping to make hand grenades in the unsuccessful May Uprising of 1849. And yet the Baur au Lac, still owned by the same family today, played a major role in the life and work of Richard Wagner.

A regular guest at the hotel was Wagner’s friend and backer, Franz Liszt. It was here that, for Liszt’s 45th birthday, Wagner performed the premiere of the first act of Die Walküre, with Liszt on the piano and Wagner as Hunding and Sigmund.

It was also at the Baur au Lac that Wagner first recited the libretto for his Ring cycle over four nights in 1853, the high drama of the performance making up for the short stature of the composer. In the audience was Otto Wesendonk, a wealthy silk merchant, who with his wife Mathilde lived at the Baur while their villa was being constructed.

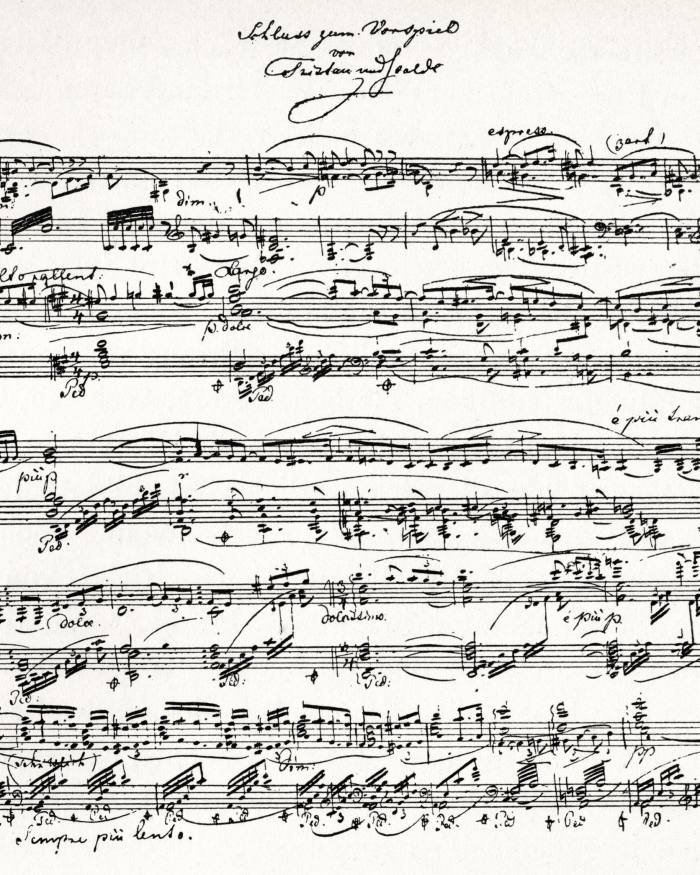

The Wesendonks became enthusiastic patrons. When their villa was finished, they invited the Wagners to stay in the house next door, the “Asyl” (“haven”). There, Wagner composed Tristan und Isolde and the Wesendonk Lieder. His muse for the former and poet for the latter was Mathilde Wesendonk. When their liaison was revealed, Wagner left for Italy, concluding his nine-year stay in Zürich.

The Villa Wesendonck sits in a beautiful park above the lake, and today houses Zürich’s exquisite museum of non-European art. Across the way is Villa Schönberg, built on the site of the “Asyl”, with a bust of the maestro in the garden (open to the public). It is a romantic, secluded neighbourhood, which, although only a 20-minute walk from the discreet and cosmopolitan luxury of the Baur au Lac, feels like the countryside.

James Joyce

For many, the Platzspitz evokes the social experiment of the 1980s when the city authorities designated the park as a tolerated but supervised zone for drug usage, with the so-called “Needle Park” attracting up to 2,500 addicts a day until its closure in 1992. Today, however, it is back to being a delightful space animated by happy picnickers and well-coiffed dogs.

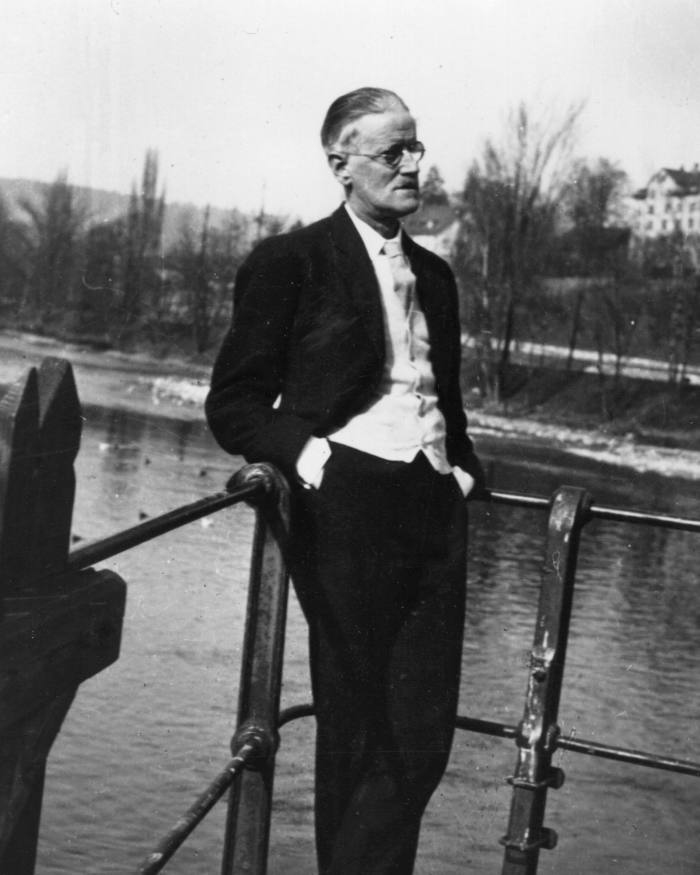

James Joyce spent both wars in Switzerland and wrote much of Ulysses here. One of his favourite spots in the city was the tip of this park where Zürich’s two rivers, the elegantly contained Limmat and the feral Sihl, meet. There you will find two quotes from Finnegan’s Wake: “Yssel that the limmat?”; “legging a jig or so on the sihl”.

A few minutes from the park lies Zürich’s main street, the Bahnhofstrasse. During the first world war, when Joyce arrived in Zürich, it was nicknamed the “Balkanstrasse” on account of the many spies, black marketeers, anarchists and other exotics who flocked there. Joyce associated the street with his declining eyesight, as described in his poem “Bahnhofstrasse”.

The epicentre of émigré life: Bellevueplatz

The area around the Bellevueplatz is the nucleus of émigré life in Zürich. The Café Bar Odeon has welcomed artists, scientists, anarchists, pacifists, socialists and every other -ist who happens to be in town. It is only half its original size (although the other half is well preserved as a chemist shop next door), but still every bit the classic Art Nouveau grand café, the perfect place for a coffee or a cocktail, or a cigar on the terrace outside. Across the street is the Terrasse, another popular choice for émigré artists over the years.

A few metres away stands the glorious Kronenhalle restaurant with its Braques, Chagalls and Picassos. A regular patron, with a particular fondness for Schnitzel and Goulasch, was Joyce and it was here that he last dined out.

In the Kronenhalle’s guestbook is a poignant entry from November 1940 by the Jewish French jazz composer, Ray Ventura: “Après une guerre aussi douloureuse, on croit rêver en se retrouvant à la Kronenhalle dans un pays aussi sympathique”. (“After living through such a painful war, it feels like a dream to come to the Kronenhalle in such a pleasant land.”)

Today, Zürich remains a place that is welcoming, cosmopolitan and deeply cheering, a small city with a big heart in which bohemia effortlessly lives alongside bourgeoisie.

Do you know of any other émigré haunts in Zürich? Share them in the comments below. And follow FT Globetrotter on Instagram at @FTGlobetrotter

Cities with the FT

FT Globetrotter, our insider guides to some of the world’s greatest cities, offers expert advice on eating and drinking, exercise, art and culture — and much more

Find us in Zürich, Melbourne, Hong Kong, Tokyo, New York, London, Paris, Rome, Frankfurt, Singapore, Miami, Toronto, Madrid and Copenhagen