A heated debate transpired between officials in a back office of Khartoum International Airport. They feared that inspecting the plane would vex the country’s increasingly pro-Russian military leadership. Multiple previous attempts to intercept suspicious Russian carriers had been stopped. Ultimately, however, the officials decided to board the plane.

Inside the hold, colorful boxes of cookies stretched out before them. Hidden just beneath were wooden crates of Sudan’s most precious resource. Gold. Roughly one ton of it.

This incident in February — recounted by multiple official Sudanese sources to CNN — is one of at least 16 known Russian gold smuggling flights out of Sudan, Africa’s third largest producer of the precious metal, over the last year and a half.

Multiple interviews with high-level Sudanese and US officials and troves of documents reviewed by CNN paint a picture of an elaborate Russian scheme to plunder Sudan’s riches in a bid to fortify Russia against increasingly robust Western sanctions and to buttress Moscow’s war effort in Ukraine.

The evidence also suggests that Russia has colluded with Sudan’s beleaguered military leadership, enabling billions of dollars in gold to bypass the Sudanese state and to deprive the poverty-stricken country of hundreds of millions in state revenue.

In exchange, Russia has lent powerful political and military backing to Sudan’s increasingly unpopular military leadership as it violently quashes the country’s pro-democracy movement.

Former and current US officials told CNN that Russia actively supported Sudan’s 2021 military coup which overthrew a transitional civilian government, dealing a devastating blow to the Sudanese pro-democracy movement that had toppled President Omar al-Bashir two years earlier.

“We’ve long known Russia is exploiting Sudan’s natural resources,” one former US official familiar with the matter told CNN. “In order to maintain access to those resources Russia encouraged the military coup.”

“As the rest of the world closed in on [Russia], they have a lot to gain from this relationship with Sudan’s generals and from helping the generals remain in power,” the former official added. “That ‘help’ runs the gamut from training and intelligence support to jointly benefiting from Sudan’s stolen gold.”

At the heart of this quid pro quo between Moscow and Sudan’s military junta is Yevgeny Prigozhin, a Russian oligarch and key ally of President Vladimir Putin.

The heavily sanctioned 61-year-old controls a shadowy network of companies that includes Wagner, a paramilitary group linked to alleged torture, mass killings and looting in several war-torn countries including Syria and the Central African Republic (CAR). Prigozhin denies links to Wagner.

In Sudan, Prigozhin’s main vehicle is a US-sanctioned company called Meroe Gold — a subsidiary of Prigozhin owned M-invest — which extracts gold while providing weapons and training to the country’s army and paramilitaries, according to invoices seen by CNN.

“Through Meroe Gold, or other companies associated with Prigozhin employees, he has developed a strategy to loot the economic resources of the African countries where he intervenes, as a counterpart to his support to the governments in place,” said Denis Korotkov, investigator at the London-based Dossier Center, which tracks the criminal activity of various people associated with the Kremlin. The center was started by Mikhail Khodorkovsky, once the richest man in Russia, now living in exile in London.

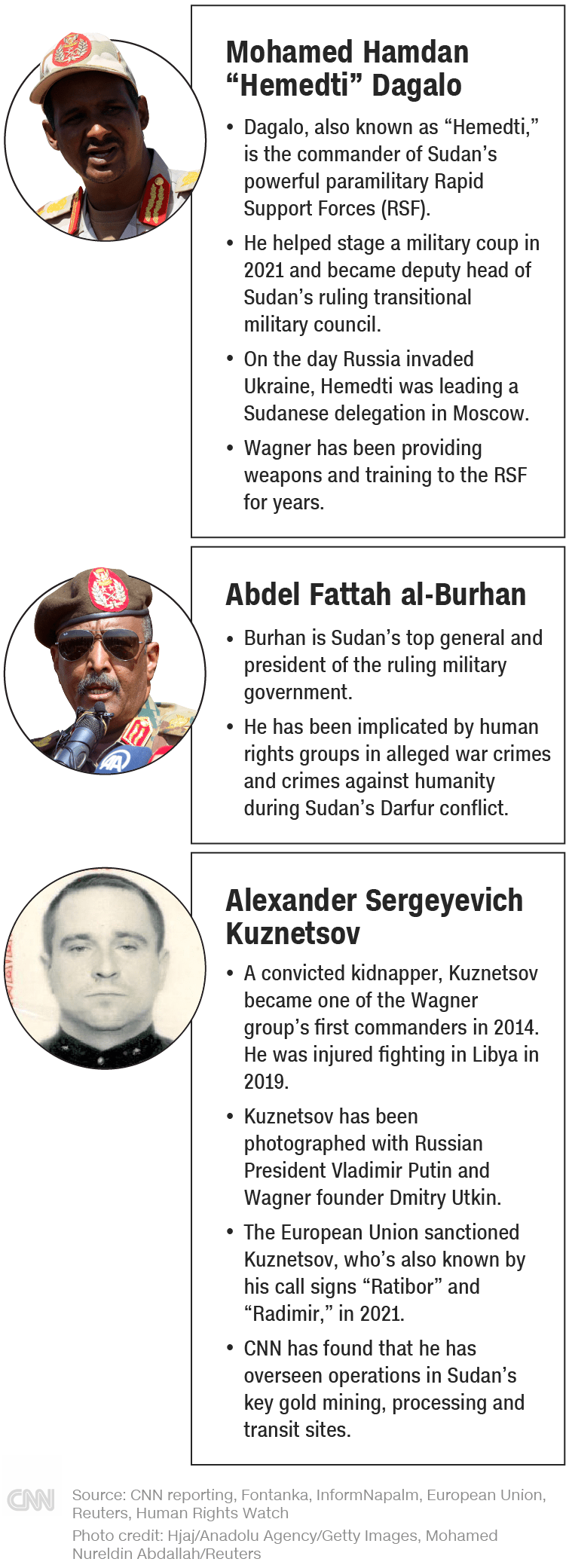

CNN, in collaboration with the Dossier Center, can also reveal that at least one high-level Wagner operative — Alexander Sergeyevich Kuznetsov — has overseen operations in Sudan’s key gold mining, processing and transit sites in recent years.

Kuznetsov — also known by his call signs “Ratibor” and “Radimir” — is a convicted kidnapper who fought in neighboring Libya and commanded Wagner’s first attack and reconnaissance company in 2014. He is a four-time recipient of Russia’s Order of Courage award and was pictured alongside Putin and Dmitri Utkin — Wagner’s founder — in 2017. The European Union sanctioned Kuznetsov in 2021.

The growing bond between Sudan’s military rulers and Moscow has spawned an intricate gold smuggling network. According to Sudanese official sources as well as flight data reviewed by CNN in collaboration with flight tracker Twitter account Gerjon, at least 16 of the flights intercepted by Sudanese officials last year were operated by military plane that came to and from the Syrian port city of Latakia where Russia has a major airbase.

CNN has reached out to the Russian foreign ministry, the Russian defense ministry and the parent organization for the group of companies run by Prigozhin for comment. None has responded.

Responding to the findings of CNN’s investigation, a US State Department spokesperson said: “We are monitoring this issue closely, including the reported activities of Meroe Gold, the Kremlin-backed Wagner Group, and other sanctioned actors in Sudan, the region, and throughout the gold trade.

“We support the Sudanese people in their pursuit of a democratic and prosperous Sudan that respects human rights,” the spokesperson added. “We will continue to make clear our concerns to Sudanese military officials about the malign impact of Wagner, Meroe Gold, and other actors.”

Receding into the shadows

Russia’s meddling in Sudan’s gold began in earnest in 2014 after its invasion of Crimea prompted a slew of Western sanctions. Gold shipments proved an effective way of accumulating and transferring wealth, bolstering Russia’s state coffers while sidestepping international financial monitoring systems.

“The downside of gold is that it’s physical and a lot more cumbersome to use than international wire transfers but the flip side is that it’s much harder if not impossible to freeze or seize,” said Daniel McDowell, sanctions specialist and associate professor of Political Science at Syracuse University.

The hub of Russia’s gold extraction operation lies deep in the desert of northeast Sudan, a bleached landscape peppered with gaping chasms where miners toil in searing heat, with only tents fashioned from scraps of tarpaulin and sandbags providing any respite.

Miners from those remote artisanal mines converge on al-Ibaidiya — known as ‘gold town’ — every morning, lugging sacks of gold in carts hauled by donkeys along the town’s unpaved roads. The highest bidders for their goods, many of them say, are almost invariably merchants dispatched from a nearby processing plant known by locals as ‘the Russian company.’

It’s a helter-skelter selling process that sources tell CNN is the nerve center of Russia’s gold siphoning. Some 85% of the gold in Sudan is sold this way, according to official statistics seen by CNN. The transactions are mostly off-the-books, and Russia dominates this market, according to multiple sources, including mining whistleblowers and security sources.

For at least a decade, Russia has hidden its Sudanese gold dealings from the official record. Sudan’s official Foreign Trade Statistics since 2011 consistently list Russia’s total gold exports from the country at zero, despite copious evidence of Moscow’s extensive dealings in this sector.

Because Russia has benefited from considerable government blind spots, it is difficult to ascertain the exact amount of gold it has removed from Sudan. But at least seven sources familiar with events accuse Russia of driving the lion’s share of Sudan’s gold smuggling operations — which is where most of Sudan’s gold has ended up in recent years, according to official statistics.

A whistleblower from inside the Sudanese Central Bank showed CNN a photo of a spreadsheet showing that 32.7 tons was unaccounted for in 2021. Using current prices, this amounts to $1.9 billion worth of missing gold, at $60 million a ton.

But multiple former and current officials say that the amount of missing gold is even larger, arguing that the Sudanese government vastly underestimates the gold produced at informal artisanal mines, distorting the real number.

Most of CNN’s insider sources claim that around 90% of Sudan’s gold production is being smuggled out. If true, that would amount to roughly $13.4 billion worth of gold that has circumvented customs and regulations, with potentially hundreds of millions of dollars lost in government revenue. CNN cannot independently verify those figures.

An anti-corruption Sudanese investigator who has tracked Russia’s gold dealings in Sudan for years provided CNN with the coordinates of a key Russian processing plant. When CNN arrived at the site, some five miles from al-Ibaidiya, a Soviet flag fluttered above the compound. A Russian fuel truck was parked outside.

A casual encounter with the guard — who confirmed that the facility belonged to the so-called “Russian company” — quickly turned into a tense confrontation.

The guard spoke through a walkie talkie, conveying CNN’s request to speak to “the Russian manager.” A group of Sudanese men then rushed to the scene and ordered the CNN crew to leave, before the CNN car was tailed by the security detail.

“You need to go,” another Sudanese employee at the plant told CNN. “This isn’t a Russian company. It is a Sudanese company called al-Solag.”

Al-Solag’s formation over the last year has marked a key turning point for Russia’s presence in Sudan. Under the new model, Russia’s dealings have receded into the shadows, making the arrangements more reliant on Sudan’s military leadership and further enabling Russian actors to circumvent state institutions, including regulations pertaining to foreign companies, under the guise of a local business. CNN has reached out to Sudan’s military leadership for comment, and received no reply.

‘Too much US scrutiny’

In 2021, Russia’s Sudan envoy, Vladimir Zheltov, called for an impromptu meeting with Sudanese mining officials.

Appearing visibly nervous, Zheltov demanded that Meroe Gold be “obscured” after becoming subject to “too much US scrutiny,” according to a whistleblower from Sudan’s Ministry of Mining who had first-hand knowledge of the meeting.

By June of this year, Zheltov’s demands had materialized. The transfer of Meroe Gold’s assets to the Sudanese-owned al-Solag appeared to have been completed. An analysis of the registration documents of the two companies revealed striking similarities, including two identical lists of legal penalties.

Under Sudanese law, a company wishing to transfer their holdings must also transfer judgments against it. It is illegal to have an undeclared foreign partner.

Sudan’s anti-corruption committee, a watchdog set up to assist Sudan’s transition to democracy, then blocked the attempted subterfuge, according to a former civilian official with direct knowledge of the events. The anti-corruption committee sent a detailed report to the armed forces in September 2021 with evidence of the Meroe Gold transfer to al-Solag, urging them to stop what they dubbed a “crime against the state.”

The watchdog also accused the military of complicity in Russia’s dealings, drawing the ire of the military leadership who lambasted the committee for “harming the armed forces,” according to the former civilian official.

“The Russians and Sudanese officers saw the civilians in the government as an obstacle to their plans,” the former official added.

In October 2021, a month after the anti-corruption committee stopped the transfer of holdings from Meroe Gold to al-Solag, Sudan’s military staged a coup — which US official and former official sources accuse Russia of backing — and the junta immediately dismantled the committee.

“Russia is a parasite,” the former official told CNN. “It pillaged Sudan. And it has exacted a very large political penalty by terminating a democratic project that could have turned Sudan into a great nation.”

Gen. Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, leader of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) paramilitary unit, is a key beneficiary from Russian support, as the primary recipient of Moscow’s weapons and training. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan — the country’s military ruler — is also believed by CNN’s Sudanese sources to be backed by Russia.

Human rights groups have implicated both Burhan and Dagalo (known as Hemedti) in alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity during Sudan’s Darfur conflict that started in 2003.

On the same day that Russia launched its 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Hemedti was heading a Sudanese delegation in Moscow to “advance relations” between the two countries.

Wagner boots on the ground

On a dusty border-crossing between the CAR and Sudan in March 2019, a bespectacled 34-year-old Russian frantically sent his boss — Meroe Gold owner Mikhail Potepkin — a plea for help.

“Radimir is pissed that no one was warned,” wrote Aleksei Pankov in a Telegram conversation which the Dossier Center shared with CNN. He was referring to Kuznetsov, the menacing high-level Wagner operative, depicted as manning the border alongside Sudanese intelligence operatives.

“Tell Radimir that it was a ‘closed’ operation. That’s why we didn’t warn him about it,” came Potepkin’s reply.

“F**k, Radimir is scary. I almost s**t my pants,” Pankov wrote back.

This exchange is part of a string of evidence collected by CNN that establishes Kuznetsov as a key Wagner enforcer across key locations in Sudan.

CNN has also seen official Sudanese communiques referencing Kuznetsov as a “problematic” armed Russian who was overseeing security at the Russian gold processing plant near al-Ibaidiya. A source familiar with Meroe Gold’s activities in Sudan told CNN that Kuznetsov also frequented the company’s offices in Khartoum.

Wagner operatives deploy to Sudan on a rotational basis, the Dossier Center told CNN, and Kuznetsov may be one of several Wagner men in the country. These are strategically dispatched to protect Russia’s smuggling scheme that has grown in importance since Russia launched its war on Ukraine.

Those Wagner operatives appear to be part of a growing climate of fear as Moscow tightens its grip on Sudan’s gold pipeline, sources say.

Several local journalism networks whose work CNN has drawn on for this report — such as Mujo Press, al-Bahshoum and activist journalist Hisham Ali’s Facebook page — have been targeted in recent months, driven into exile under the threat of assassination. Ten protesters were gunned down in demonstrations in June alone, three of whom were prominent pro-democracy activists. CNN security sources believe they were deliberately targeted.

High-level Sudanese officials repeatedly urged CNN’s Nima Elbagir to steer clear of protest sites. Since CNN began this investigation, Elbagir has been put on the military junta’s hit list, according to multiple Sudanese security sources.

As images of Russian tanks encircling Kyiv were flashing on TV screens at Khartoum International Airport, employees watched as the plane laden with cookies and gold took off last February. Senior army brass had intervened and a sense of foreboding set in.

Some of the officials who uncovered the haul were reassigned, some to regional duty stations, and others were sent to army reserves, according to a source with direct knowledge of the incident.

“They paid for doing their jobs,” the source told CNN.

CNN’s Jennifer Hansler contributed to this report.