Receive free Twitter Inc updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest Twitter Inc news every morning.

Something big just happened in the world of Twitter advertising.

For quite some time, the internet’s town square has been clogged with adverts for pet products, household doodahs, gadgets and garden ornaments, as if the Betterware Catalogue had been reinvented by Wish. The ads all use the same template: a promoted tweet from a blue-tick account, a speeded-up video, and a link to an identikit shopfront badged something like Zotu, Dulo or Loza.

The frequency with which these ads appeared has caused Twitter users quite a lot of irritation . . .

Anyone else have loads of these promoted ads pop up? Selling crappy gadgets. Literally every 10 tweets on my feed. And others pop us as soon as I block them pic.twitter.com/UPjFNp2gkk

— Cian (@ciannotseean) June 24, 2023

. . . with the community’s “added context” feature being used to raise concerns about the quality and legal status of some products:

I love how the ads I now get on Twitter constantly have community notes saying “this is illegal” or “this will literally kill you if you use it”. pic.twitter.com/KCRW0M7Sf8

— 🐱 Hugo the pink cat 🐱 (@HugoThatPinkCat) July 5, 2023

As it happens, Alphaville was tracking several dozen of these ad accounts. And in the past few hours, every single one was suspended.

To be clear, there are a lot of dropshipper ads on social media. The specific accounts we’re referring to were promoting a fleet of commerce sites — Tace, Vore, Toba — that are aesthetically and functionally identical. They all use the same build of WordPress and they all rely on Woocommerce, an open-source plugin for small merchants.

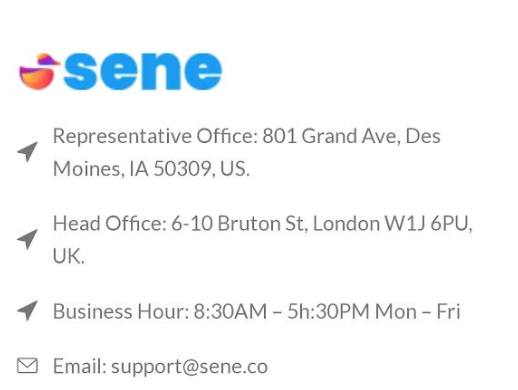

Another repeated theme among these ecommerce sites is unlikely-sounding operating addresses. The head office of Sene, for example, is the site of what was once The Square restaurant in Mayfair:

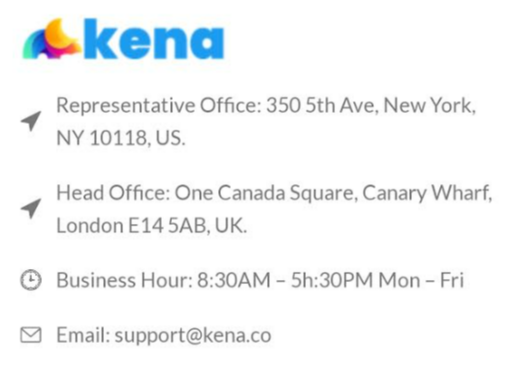

. . . and Kena appears to operate out of some super-prime real estate:

Having a bogus business address on an ecommerce website is not allowed, at least in the UK. The Advertising Standards Authority requires ads targeting UK consumers to be accurate and not contain any misleading information, including about where the operator is based. For example, in 2019 the ASA banned an ad for Wandsworth Plumbers after finding no evidence that it had a permanent base in Wandsworth.

An ASA spokesman said that without an investigation he couldn’t say whether any of the Twitter ads would be subject to its regulation.

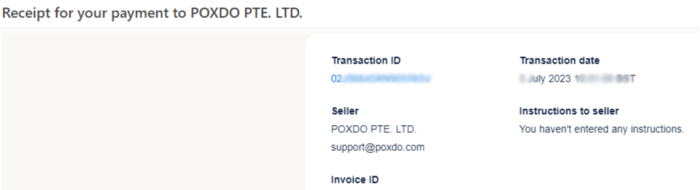

So who’s really behind the sites? Our test orders through different shopfronts all resolved to the same company, a Singapore-registered dropshipping agent called Poxdo.

Much of the text on Poxdo’s website is identical to other, seemingly unrelated websites so it’s tricky to know what to trust. The contact page lists an address in downtown Singapore, within the Bugis Cube shopping centre, and mentions a warehouse in Yiwu, in the Zhejiang province of China.

Yiwu, “the world’s largest wholesale market for small manufactured goods”, was recently profiled by our colleagues on MainFT:

With its 75,000 stores, Yiwu has been nicknamed China’s trinket town, the centre of a multibillion-dollar trade in everything from Christmas decorations to toys and umbrellas to pencils. The city some 300km south-west of Shanghai is also at the heart of an experiment over the past 15 years to internationalise the renminbi as Beijing seeks to strengthen the role of the world’s second-largest economy in the global financial system.

Public documents filed at Singapore’s corporate registry show Poxdo PTE Ltd was established in May 2020 and name two directors: Lee Ming Chung, a citizen of Singapore, and Nguyen Dac Manh of Ha Noi, Vietnam.

Our efforts over several weeks to contact either director proved unsuccessful. Emails direct to Poxdo also went unanswered. Company secretary Thung Sai Fun of Ace Global Accountants and Auditors, when contacted on LinkedIn, did not respond to our requests for information about Poxdo and has since switched her profile to private.

Under Singapore law, a company must have at least one resident director on its board at all times. Foreigners setting up Singapore companies often recruit a local resident to be a passive, nominee director. Lee Ming Sung is a director of more than 60 disparate Singapore-incorporated companies and a shareholder of none, his registry record shows. (We’re including the original documents here because while all filings are public, the Singapore government’s BizFile service charges up to $50 per download request.)

The given address on the registration form for Nguyen Dac Manh, Poxdo’s other director and 100 per cent shareholder, is for an area of Hanoi rather than a residence or a specific street. Over the past two weeks we have reached out to numerous people with that name — there’s a Nguyen Dac Manh who promotes Vietnam real estate, for example, and a Nguyen Dac Manh who appears in promotional videos for Lazada, the Singapore-based ecommerce group. So far, none has responded.

An odd, possibly irrelevant tangent can be found buried on Poxdo’s website. As well as the visible pages detailing the company’s operations, there’s the unused framework of a WordPress- and WooCommerce-based storefront lying dormant in the background. Among its public but unlisted sections are template “author” and “blog” pages with holder posts credited to “Maximus Brainsby”. (The same framework appears elsewhere on the ecommerce web, such as for the Beeco storefront.)

Maximus Brainsby Ltd was the name of a company incorporated in the UK in 2019 by a Vietnamese resident, Tuan Hoang Anh, and struck off in 2021. The name also appears on a messageboard for users of Shopify, in a thread complaining about traffic received from a product research tool called Pexgle. One poster quotes an email they say was signed “Maximus Brainsby, Co-Founder, Pexgle.”

Vietnam-based Pexgle advertises itself as an “all-in-one hunt winning products and ads toolkit for dropshippers and ecommerce entrepreneurs”. We’ve asked Pexgle and everyone we could find named Tuan Hoang Anh about dropshipping and Twitter ads; none has yet responded. If anyone ever wants to speak to us about anything, we’ll update this post accordingly.

Asked to comment on the account suspensions, Twitter’s press office gave its standard automated response: