Plans to force separating couples in England and Wales into mediation to avert legal battles over asset division and contact with children have been criticised by family dispute professionals, who warn that making feuding former lovers reach agreement out of court is unviable.

The UK government has proposed mandating mediation before court action in most cases, partly to ease pressure on an overwhelmed justice system that has left families waiting almost one year on average for proceedings involving children to conclude.

Ministers have also pitched the reforms as a way to protect children from witnessing protracted and upsetting court disputes involving their parents. Mediators and lawyers said that while the sessions were helpful in the right circumstances, imposing them would be unworkable and in some cases harmful.

“You have the family mediation community speaking as one, saying: ‘No, we’re not going to do compulsory mediation’,” said Caroline Bowden, director of the Family Mediation Council, which co-ordinates regulation of professional family mediators, and a solicitor at law firm Anthony Gold.

Anna Vollans, chair of the Family Mediators Association and founder of Leeds-based Vollans Mediation, said it “offends one of the core principles of mediation, which is that it’s a voluntary process”.

While most separating couples avoid formal legal proceedings, 52,200 cases involving children began last year, according to the Ministry of Justice. These are typically about living arrangements and contact time.

There were a further 39,400 court applications relating to financial affairs. Typical disputes involve what to do with the family home and how to carve up proceeds if it is sold, and division of other assets.

The process is distinct from divorce, to which separation is usually a precursor for married couples. The 50-year-old law that governs how wealth is split in divorce is under separate review by the Law Commission, the independent body that recommends reforms to legislation. More partners are separating without divorcing, though: more than half of children born in 2021 were born to unmarried parents, according to official data.

Joanne Edwards, partner at law firm Forsters and chair of the family law reform group at Resolution, a family justice association, said people who went to court faces “horrific” waits for separation cases to conclude.

Official data published last week showed that, as of the first quarter of this year, the average duration of private family law cases involving children had doubled since 2016 to 47 weeks.

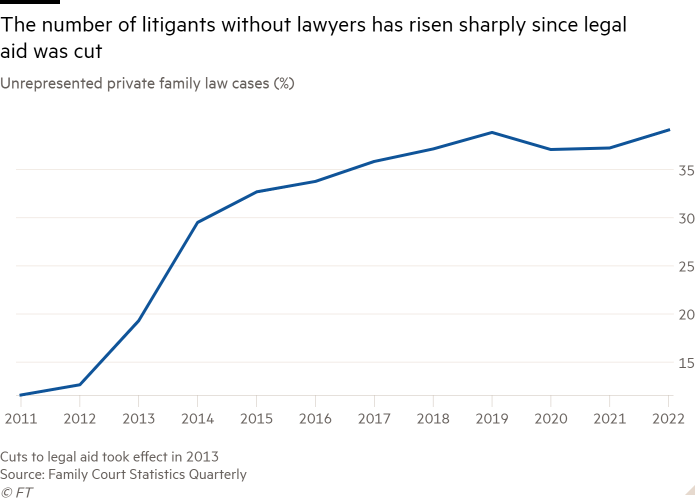

Ministers have blamed the delays on Covid-19, but lawyers said the pandemic had only exacerbated problems caused by deep cuts to legal aid a decade ago that left many embroiled in messy splits without legal representation.

“One of the main reasons the court system is on its knees is because it’s been flooded by litigants in person,” said Vollans, adding that judges were “having to spend much more time with litigants to manage the process”.

Jan Ewing, research fellow in family law at Exeter university, said ex-partners had a “perverse incentive” to go to court because application fees of between £200 and £300 to bring a case are minimal compared with the costs of mediation or legal advice.

The share of cases in the family courts in which neither party is represented has trebled since 2012 to account for 40 per cent of the total, MoJ figures show.

Bowden said that those who brought such action often had “completely the wrong expectations — thinking they will be vindicated [by the court], which almost never happens”.

Some judges have raised concerns about the volume of unnecessary cases. One in Bristol complained that he had been asked to rule on which junction a child should be handed over on the M4 motorway.

Private arbitration proceedings held by lawyers or even retired judges were increasingly popular alternatives to court for estranged partners on higher incomes, lawyers said.

Mediation tends to be cheaper than private arbitration. Current or former solicitors or social workers preside over sessions that aim to result in agreement. A court can make the accord binding if both parties wish, although that is mostly sought in matters relating to finance.

To encourage more separated couples to find common ground, the government introduced a voucher programme two years ago offering £500 towards the costs of mediation. About two-thirds of those who have taken part in the scheme reached full or partial agreement away from the courts, according to the MoJ.

On the back of these successes, ministers put forward proposals in March for mediation to become mandatory in “all suitable low-level” cases. A public consultation on the plans closed last month.

Mediators have welcomed the voucher scheme but warned that compulsion would backfire. Ewing described it as a “good process, but it’s not for everyone — if you force someone to go into it, they won’t go in with the right mindset”.

Lawyers also warned that mandatory mediation posed risks for survivors of domestic abuse, not least since fears of reprisals mean some do not raise a partner’s violence at the start of separation cases.

The MoJ stressed in its consultation that victims would not be obliged to attend sessions with their former partner, but Edwards questioned whether the system would have enough resources to spot all such instances.

People working in the family justice system make a broader case for public funding of advice and counselling at an early stage of separations. Such a system would make it “far less likely that agreements will break down later” and end in court, said Edwards. More limited reforms may be more likely, however.

Would-be litigants are in theory already required to first attend a meeting with a mediator to learn about alternatives to court. But little more than one-third attend owing to various exemptions, according to MoJ data.

Lawyers said ministers could tighten the rules on appearing at the information sessions, improving awareness of ex-partners’ options other than legal action.

The MoJ said its plans would “spare thousands of separating parents and their children from enduring lengthy courtroom battles and hefty legal bills — while ensuring the most urgent cases such as those involving domestic abuse are heard by courts as quickly as possible.

“Our consultation has now closed and we will publish our response in due course.”