WARNING: This article contains graphic content and may affect those who have experienced sexual violence or know someone affected by it.

B.C. woman Lenore Rattray is turning the typical true crime podcast on its head with her first-person telling of her brutal kidnapping 31 years ago.

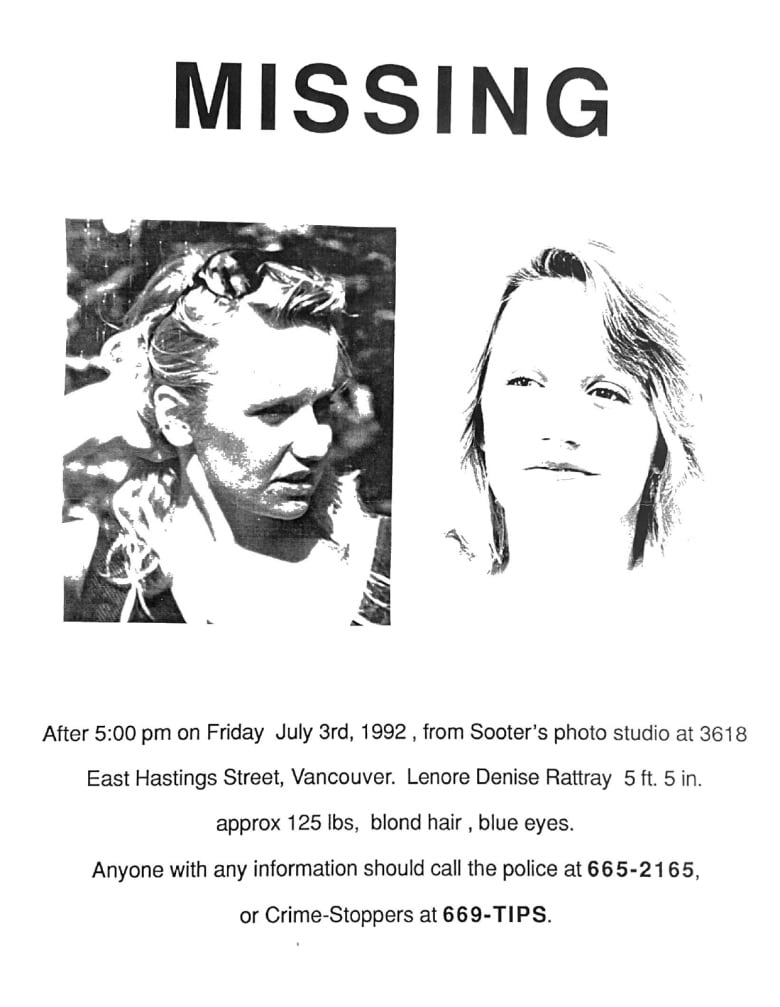

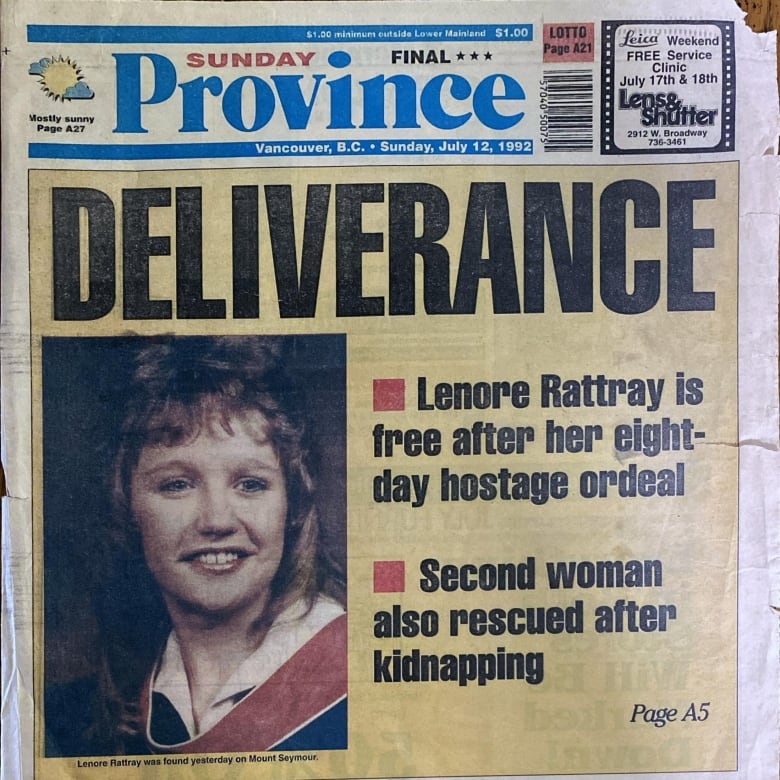

A man on the run from Ontario police abducted her from the photo studio where she worked in downtown Vancouver on July 3, 1992 and held her captive for eight days until police found her hogtied in the woods near Mount Seymour.

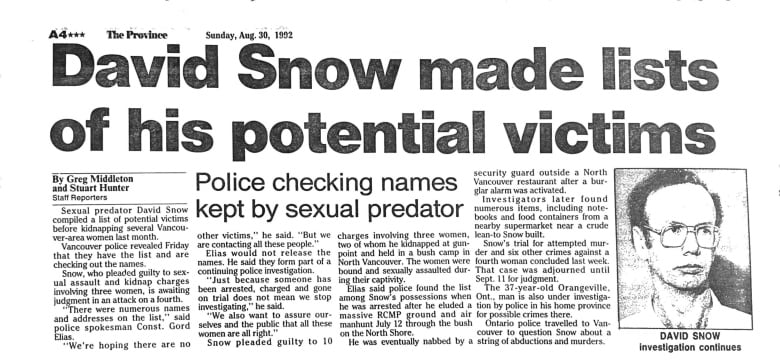

David Snow, later convicted of a double murder and multiple counts of kidnapping and sexual assault, forced Rattray to walk, at gunpoint, across the Ironworkers Memorial Bridge to his camp on the North Shore. That’s where he held her for a week, repeatedly beating and sexually assaulting her.

Her abuser is serving a life sentence after being apprehended following a manhunt. However, Rattray, now 52, says she continues to feel the impact of the shocking incident three decades later.

It’s been 31 years since a Vancouver woman was abducted by wanted killer David Snow, who held her captive for eight days. Lenore Rattray fought for years to keep her ordeal private, but now, she says she’s finding healing through telling her story. Warning: This story contains discussion of sexual assault.

She is now set to release a podcast about her abduction called Stand Up Eight.

In the first detailed interview with media since her abduction, she spoke to CBC News about the impetus for her podcast and her feelings during the week-long ordeal.

The Early Edition14:03An interview with Lenore Rattray

This week marks thirty one years since Lenore Rattray was abducted from a photo studio in Vancouver by wanted killer David Snow, who held her captive for eight days. She fought for years to keep the details of her ordeal private, but now, she says she’s finding healing through telling her story. She sat down with the CBC’s Jennifer Wilson for her first media interview in decades. A warning to listeners — this story contains discussion of sexual assault that some may find distressing.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What happened to you over that eight-day period? What was going through your mind?

I think I moved here [Vancouver] at the end of April [1992], so fast forward … early July. I was working by myself and … I see now how he stalked me.

He saw all of the things that he was looking for — a young woman working alone. Nobody else was going to be there at closing time. He had asked all the right questions. He’d been in the studio a couple of times.

He came back at closing time and pulled a gun and eventually took me to the woods.

Everything changed. I had no idea if I was going to live to see real life again.

The only thing I could do was trust. And that’s the only way.

He was an animal. I don’t even like to give him a name. I don’t have an anger for it. He’s very sick man, a very sick person.

He was keeping me and he was going to get use out of me however he could.

It’s not just the physical — as females we absorb all of the other sensory stuff that are going on in an assault.

I hear that. I smell him.

Initially, it was fear. And then it just it morphed into, “Just survive.” In the moment you don’t really think of it, but you just adapt.

There were stories in the media about what exactly that torture and assaults entailed. And you were upset by that. You wanted those details to remain private. You didn’t think that they were for public consumption. Now you’re making this podcast. Why now are you willing to have those details out there? And what do you think it achieves to have those intimate details out there?

It’s empowering for me for the first time. That understanding came from doing this in PTSD therapy.

I didn’t just jump out there and start talking about this. This has been a slow build to get here, to get to a point where I can talk about it and see that young girl vividly in those scenarios.

There was no way that I knew how I was going to live.

But you did.

I did.

The way that it turned out that I’m alive is, he did find another young lady working by herself. It was on July 11.

He took her and forced her to drive her car to where we were camped and, for some reason, [he] brought me with them and took us to Mount Seymour.

A brilliant RCMP officer received the call, and put two and two together, and found the car and found us.

Do you remember that moment when the officer turned up?

Absolutely.

What was that moment like?

I was in the back of the car. She [the other kidnapping victim] was driving.

I remember, her looking at me, and just the fear in her eyes was … I was just numb to it all.

Eventually, we were separated. He tied me up and left me in one section of this wooded area. I could hear him beating her and her trying to get away.

And then the next thing I know, he put his hand on my shoulder and he said, “The police are at the car. I’m on my way now. I’m not gonna hurt you anymore.”

And I looked, and he just, he almost like melted into the bush.

Let’s talk about your use of the word “prey,” how you realized that you were prey. How has that concept stayed with you and impacted you even 30 years later?

The term prey — in terms of predator and prey — it pretty much sums it up how I feel walking around in life. And I never did before that.

I will struggle to carry that in terms of my daughter and knowing and seeing how she is seen. I just see a real sickness that exists and a risk that we as women carry.

It changed me forever in terms of how I looked at male relationships.

[We] often, I’d say look at true crime through the lens of the criminal perpetrator having this superhuman element about him — usually it’s a him.

Me telling this story now about the superhuman that survived this and continues to, 30 years later, and raise a family and have a job — I want to open up conversations on truly understanding the impact of trauma and the connection it has to our whole selves.

Sexual trauma never leaves you. I see how carrying this story in silence for so many years, I see how it made me sick.

I’m not saying that everybody should tell their story. Everybody has their own way of processing but for me, if I didn’t start talking about it, it was becoming like a darkness in me.

There’s a quote by Maya Angelou. It says, “There’s no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside of you.”

By setting this story free, finally, now that I’m ready … I feel growth whenever I do.

Support is available for anyone who has been sexually assaulted. You can access crisis lines and local support services through this Government of Canada website or the Ending Violence Association of Canada database. If you’re in immediate danger or fear for your safety or that of others around you, please call 911.