The house Raymond Lafontaine built 21 years ago is filled with family mementoes.

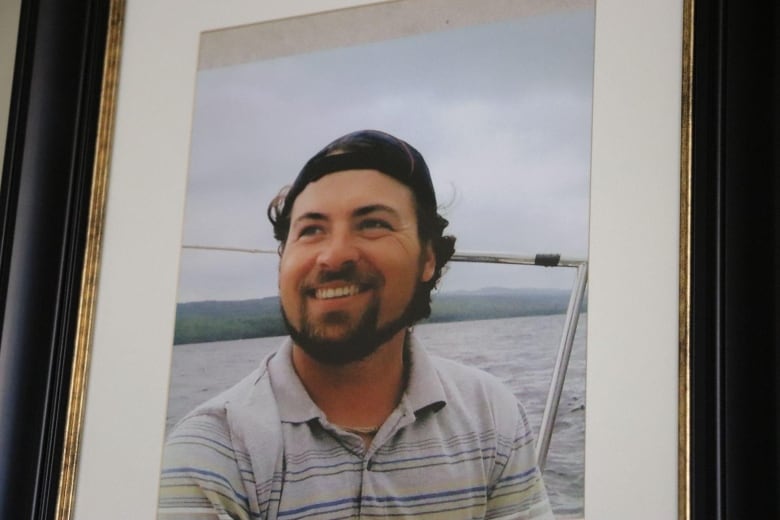

Framed photos of his grandchildren line the walls. Stained glass windows handcrafted by his brother are installed in the living room, which looks out over majestic water of Lac-Mégantic, Que. And on the dresser sits a single candle, embossed with a photo of his son, Gaétan.

But Lafontaine’s once-lively home is quiet now.

Gaétan is dead; Lafontaine’s grandchildren, orphaned. Raymond and his wife are separated. The construction business he built is up for sale, his surviving sons burnt out from stress.

Ten years ago, early in the morning of July 6, 2013, the Lafontaine family was ripped apart.

Gaétan, and Raymond’s two daughters-in-law, Karine Lafontaine and Joanie Turmel, along with an employee, Marie-Noëlle Faucher, were among 47 people killed after a train carrying crude oil derailed on the main street of Lac-Mégantic, a town of about 6,000 located in Quebec’s Eastern Townships, just north of Maine.

Another of Lafontaine’s sons, Christian, called him early in the morning with the news.

“The train derailed,” Lafontaine recalls Christian telling him. He lights a cigarette and takes a seat on his porch, looking out at the pouring rain. “I went down there, and it was right there where they all burned.”

“Ever since this happened, we don’t feel like we’ve been living. Our kids were a gift from above.”

To mark the 10th anniversary of the tragedy, townspeople will set out on a candlelight walk just after 1:00 a.m. on July 6 — the hour that the train derailed.

But Lafontaine will be staying home.

He says grieving for his life as it was before 2013 is hard enough — never mind reliving the moment that left his family devastated.

“Every day we think about our kids. Every day this tragedy haunts us,” said Lafontaine. “It’s 10 years of nightmares.”

‘We deserve to be happy again’

Isabelle Boulanger will do what she has always done on the anniversary of her son Frédéric Boutin’s death — release butterflies at his grave.

Frédéric’s body was found outside his apartment building on Frontenac Street after the inferno. He was 19.

“He was always happy,” said Boulanger.

“He always wanted to do some stuff. And I kept saying to him, ‘Don’t be in such a hurry. You’re young. You have plenty of time in front of you.’ But you know, he wanted to do everything now.”

To this day, Boulanger says she still can’t pass by Frontenac Street, where her son died.

“I guess that I just feel like it’s a graveyard,” she says.

Isabelle Boulanger shares how she deals with the loss of her son, Frédéric Boutin, who was one of the 47 killed when a train carrying oil derailed in the middle of her town in 2013.

Boulanger finds solace in small things.

“We’re lucky enough that we had a full body, and we could put him in a coffin,” she says, unlike most of the victims’ families.

Boulanger and her family have worked hard to overcome losing their “charming and loving kid.”

“We were so sad all the time … and at a certain point we just looked at ourselves, my husband and my daughters and I, and we just said, ‘Frédéric would not like us to be sad all the time,'” said Boulanger.

“We deserve to be happy again.”

‘There’s no good place for the rail bypass’

Walking across the farm where Boulanger grew up on the outskirts of Lac-Mégantic, she said the family will soon have new difficulties to overcome.

After years of delay, the provincial and federal governments are making good on a promise to move the railway line that still runs through the centre of town — past the street where the train derailed and exploded, and past the memorial to the 47 victims.

The planned bypass cuts right through the farm where Boulanger’s mother still lives.

Property owners along the new route have been told the government will take physical possession of expropriated parcels of land required for the project in August.

Seeing the trains run past the farm, day in and day out, will not be easy.

“It’s going to be a reminder, every single day, that that train took my son,” said Boulanger.

She plans to continue fighting the new route alongside their neighbours, but knows there isn’t a perfect solution.

“There’s no good place for the rail bypass. There are going to be unhappy people wherever they put it.”

Denis Godin agrees.

Godin, Lac-Mégantic’s director of security, says although some residents are unhappy with the new route, others will be relieved trains will no longer roll through town.

Since the disaster, trains have been forced to slow down as they make the curve on the street where the diesel cars derailed. That and other precautions make townspeople safer, Godin said.

Recovering from trauma

Godin, a volunteer firefighter for the past 32 years, was captain of the fire service in 2013.

He was supposed to be on call that July 6, but the day before he switched shifts with the director.

He drove up to his chalet, which has no cellular service.

“My kids realized there was a tragedy,” said Godin.

“They texted me and texted me, again and again. The messages weren’t getting delivered.”

Godin says his daughter drove up to his cabin once she found out he was off duty.

When she told him what had happened, Godin said he thought it was a joke.

“She said, ‘There is no more downtown. All of the town is burning.’ And then she spoke with her sister to tell her everything was OK,” said Godin, breaking down, sobbing.

He arrived in town Sunday, the day after the derailment, and helped direct the search for those missing.

“What was most important for me was to ensure our firefighters weren’t the ones to recover the bodies of the victims,” said Godin.

“Some of them would be able to recognize the victims. I saw the bodies that were pulled out, and I wouldn’t want that for my firefighters.”

In the aftermath, he says, several members of the team sought treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder.

Among them is Éric Mercier.

The volunteer firefighter worked three straight days with little rest following the derailment.

It cost him his mental health.

“I was not sleeping at all. I was sleeping something like five or 10 hours a week and had a lot of bad dreams. One night I had a nightmare and all the family [came] in my room and I didn’t want my family to see me like that.”

He says in the months and years that followed, it also took a toll on many others in the town. “There’s some people who die in the tragedy, but some … they died inside,” said Mercier.

‘We are not victims’

Mercier says he wouldn’t have made it without his wife’s support. He sought therapy and got a job in a neighbouring town to cope with the trauma.

“It was good to get out of the town, to see something else, see real life, positive life. It was very good to laugh,” said Mercier.

Mercier is still a volunteer firefighter in Lac-Mégantic and also works in fire prevention for the region.

Looking back on the changes that have taken place over the past decade, he said he’s hopeful that Lac-Mégantic will become known as more than the site of a tragic derailment, but as a place of natural beauty with a lot to offer.

“We don’t want the people of Mégantic to look like victims,” said Mercier, looking out from his office on Frontenac Street over the reconstructed downtown. “We are not victims.”

“We are people, ordinary people, who want to go further.”

In 2013 a runaway train carrying crude oil derailed and exploded in Lac-Mégantic, Que., killing 47 people and destroying the centre of town. Ten years later, trains sometimes carrying dangerous materials still roll through town, and a plan to expropriate land to reroute the rail line is dividing the community.