Lourdes Grobet, whose father would not let her attend professional wrestling matches in Mexico because she was a girl, but who later become a photographer best known for her images of the body-slamming masked luchadores, both in the ring and in their everyday lives, died on July 15 at her home in Mexico City. She was 81.

Her daughter Ximena Pérez Grobet said the cause was pancreatic cancer.

For nearly 20 years, Ms. Grobet found innovative ways to showcase her photography, including in an installation in which viewers explored a labyrinth containing life-size photos of prisons and nude men and women, different light sources and false floors.

But around 1980 she stepped into wrestling arenas, camera in hand, believing the sport known as lucha libre, which translates to “free fight,” was a part of Indigenous Mexican culture that had not been effectively explored.

“I was so astonished with the events,” she told AWARE, a nonprofit Paris organization that promotes female artists, in an interview in 2021. “And I decided that I would focus a large part of my efforts on lucha libre because here I saw what I thought was real Mexican culture.”

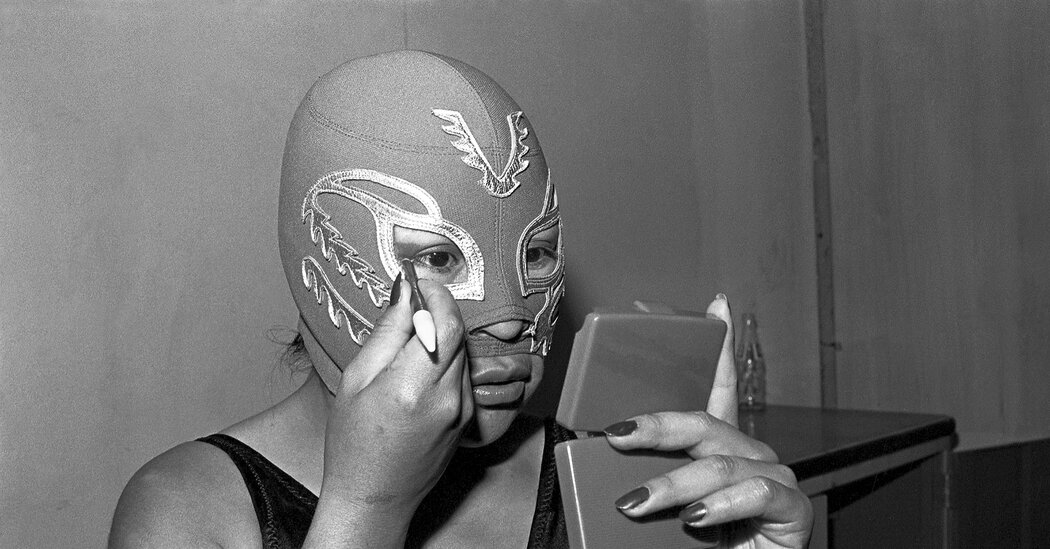

Ms. Grobet (pronounced grow-BAY) photographed wrestlers for more than two decades, less as a journalist than as an anthropologist. She followed them into arenas, their dressing rooms and their homes and to their regular jobs, rarely depicting them without the signature lucha libre masks that have historical links to Aztec and Mayan cultures and represent strength and empowerment in Mexico.

Among her arresting images: The formidable Blue Demon, in his blue mask with silver outlining his eyes, nose and mouth, sits for a portrait in a three-piece white suit, tie, pocket square and cuff links.

El Santo, one of the best known luchadores, eats a snack from an outdoor vendor.

Fray Tormenta, a priest who supported the orphans of his parish as a wrestler, wears his red and gold mask along with his gold vestments as he holds a communion host aloft in a church.

A female wrestler, also in a red and gold mask, envelops her two young sons in her cape at her home. Another feeds a bottle to her baby. Others put on their makeup. Ms. Grobet had a special affinity for the female wrestlers, for the double life they led — performing in the ring while raising families.

El Santo and the Blue Demon, two of Ms. Grobet’s favorite subjects, were the only luchadores whose faces she never saw.

“And I didn’t want to see them,” she said in an interview in 2017 for the Artists Series, online interviews by the photographer and filmmaker Ted Forbes. “The other wrestlers, I would visit in the arena,” and they would put on their masks when she started photographing them.

She took thousands of pictures of the wrestlers (and their fans), many of which she published in a book, “Lucha Libre: Masked Superstars of Mexican Wrestling” (2005, with text by Carlos Monsiváis).

The book preceded the release in 2006 of the movie “Nacho Libre,” a spoof starring Jack Black that was inspired by the life of Fray Tormenta. (Mr. Black’s character is a monastery cook, not a priest.) Ms. Grobet’s son Xavier Grobet was its cinematographer.

Shortly before the film’s release, she voiced her hope that it would treat the sport respectfully, telling The New York Times that anyone who thought lucha libre was campy entertainment was indulging in “a social class prejudice.”

Seila Montes, a Spanish photojournalist who took pictures of the luchadores from 2016 to 2018, wrote in an email, “Lourdes was a pioneer in directing her lens to common places” and finding “the sublime in the ordinary and marginal.”

Maria de Lourdes Grobet Argüelles was born on July 25, 1940, in Mexico City. Her father, Ernesto Grobet Palacio, was a cyclist in the 1932 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles who finished last in the 1,000-meter track time trial; he later owned a plumbing business. Her mother, María Luisa Argüelles de Grobet, was a homemaker.

Although Ms. Grobet said that she came from a family of “sports fanatics and body worshipers” who watched wrestling on television, her father refused to let her attend the matches in person.

“He didn’t think that was the kind of thing women should see,” she told the journalist AngélicaAbelleyra in an undated interview. “He didn’t want us to become friends with the ‘bums’ in the ring or in the audience.”

Ms Grobet was a gymnast as a girl, then a dancer. After studying classical dance for five years, she was bedridden with hepatitis, which prevented her from any exercise for an extended period.

When she recovered, she began taking formal painting classes, then studied at the Universidad Iberoamericana in Mexico City under, among others, the painter and sculptor Mathias Goeritz and the surrealist photographer Kati Horna. She graduated with a bachelor’s degree in visual arts in 1960.

As a painter, she was “looking for something in between abstraction, figuration and expressionism,” she told Ms. Abelleyra, but became uncomfortable with the medium. She switched to photography while studying in Paris in the late 1960s.

Ms. Grobet did not seek the ordinary in her photography. In Britain in the late 1970s, she took pictures of landscapes that she had altered by painting rocks with colorful house paint; later, she photographed Mexican landscapes festooned with cactuses and plants that she had painted. Some of those pictures were included in a 2020 group exhibition, “Out of Place: A Feminist Look at the Collection,” at the Brooklyn Museum.

She had solo exhibitions around the world but not in the United States until 2005, when the Bruce Silverstein Gallery in Manhattan held a career retrospective. Her works are in the collections of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the MuséeDu Quai Branly in Paris, Centro de la Imagen in Mexico City and the Helmut Gershaim Collection at the University of Texas, Austin.

In addition to her daughter Ximena and son Xavier, Ms. Grobet is survived by another daughter, Alejandra Pérez Grobet; another son, Juan Cristóbal Pérez Grobet; her sister, Maria Luisa Grobet Argüelles; her brother, Ernesto Grobet Argüelles, and six grandchildren. Her marriage to Xavier Pérez Barba ended in divorce.

In the mid-1980s, Ms. Grobet started a three-decade-long project photographing the actors in a rural Mexican regional theater troupe, the Laboratorio Teatro Campesino e Indígena.

“When I saw these performances, it was the same feeling I experienced when I first saw lucha libre,” she said in the AWARE interview. “I wasn’t taking photographs of Indigenous people, per se; I was taking photographs of cultural paradigms.”