Receive free Renewable energy updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest Renewable energy news every morning.

Nobuhiko Kubota, chief technology officer of IHI, is tasked with reinventing the nearly 170-year-old Japanese industrial conglomerate for a new era of green energy.

IHI — like its peers, including General Electric and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries — is having to race to come up with new technologies that can reduce its heavy carbon footprint, in line with climate goals. And the company, which makes products ranging from aircraft engines to turbochargers, liquefied natural gas storage tanks, boilers and rocket boosters, is currently pinning its hopes on the use of ammonia as a low-carbon fuel.

This bold bet on ammonia — a compound of hydrogen and nitrogen often used to make fertilisers — has gained little traction with investors in the absence of concrete targets for its contribution to earnings. But IHI executives say the success of its technology will have broader implications for energy policy in Japan, and in Asia more broadly.

“It doesn’t have to be the only option but the use of ammonia is one major tool to head towards carbon neutrality,” says Kubota. “The key is to obtain social acceptance for wider distribution of ammonia.”

In 2017, Japan became the first country in the world to craft a national hydrogen strategy — and, within this, it highlighted ammonia’s potential.

But, since then, Japan has fallen behind other nations in developing regulations for the use of hydrogen. More recently, the US has been catching up with the EU in hydrogen strategy, through President Joe Biden’s $369bn Inflation Reduction Act.

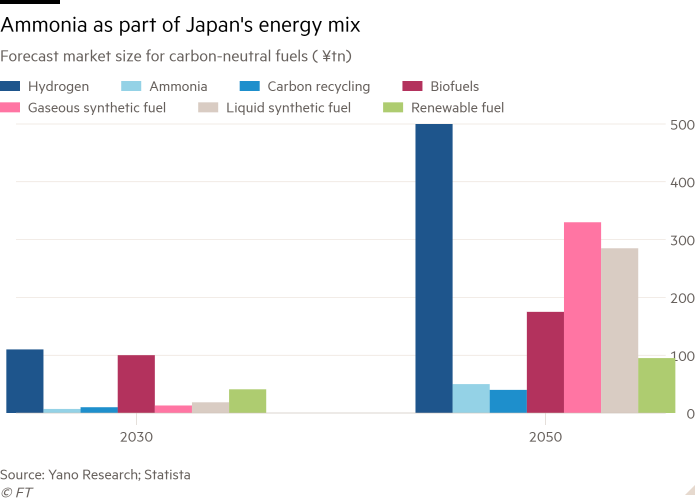

Japan, which relies heavily on coal, natural gas and oil, has set a target of generating 1 per cent of its total electricity from hydrogen and ammonia co-firing power by 2030.

To that end, in June, the government unveiled a public-private investment of ¥15tn ($104bn) to build out hydrogen and ammonia supply chains. Tokyo also has ambitions to sell the technologies of IHI and other Japanese companies to south-east Asian countries, such as Indonesia, Malaysia and India, to help them replace some coal with ammonia — thus reducing carbon emissions from coal-fired plants without retiring them.

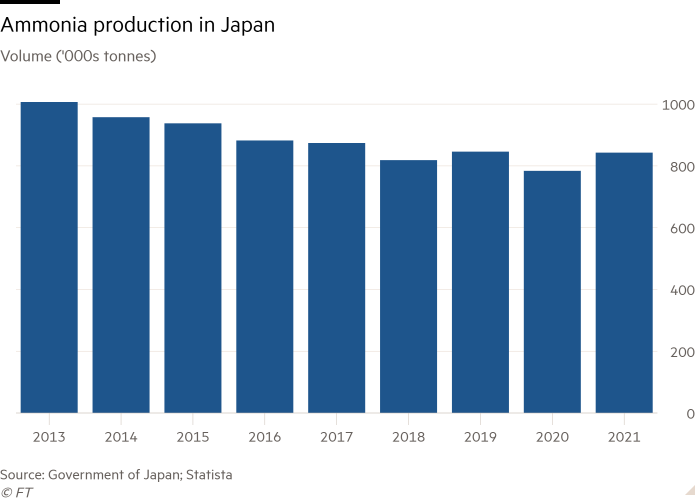

However, Japan’s promotion of hydrogen and ammonia as clean fuels met with strong pushback from other G7 nations in April, when officials and environmental groups criticised its policy for prolonging the lifespan of existing fossil fuel infrastructure. Although ammonia itself contains no carbon, its production relies heavily on fossil fuels and is not yet commercially viable.

According to research group Bloomberg NEF, co-firing a power plant with 20 per cent ammonia and 80 per cent coal will emit more carbon dioxide than combined-cycle gas turbines, which are widely used to generate electricity from gas.

But a co-firing rate of 50 per cent ammonia or more is expected to be too expensive to be competitive against other low-emission technologies.

An alternative for Japan is to import ammonia produced in countries with large renewable energy sources, although that would increase its reliance on imported energy and potentially pose economic security risks.

IHI executives say ammonia has its benefits: it is a liquid at minus 33C, while hydrogen needs to be cooled to minus 253C to become liquid. And infrastructure is already in place for shipping ammonia.

“For long-distance transport and storage, ammonia has more economic benefits than hydrogen,” Kubota says. “Our motivation is definitely not to prolong the use of fossil fuels but to contribute to the reduction of CO₂ emissions as much as possible.”

IHI aims to introduce gas turbines fired entirely by liquid ammonia in 2025 and, in January, it signed a memorandum with GE about collaborating on large gas turbines using 100 per cent ammonia. It also recently said it would spend about ¥250bn on its own ammonia development, to create a new earnings driver alongside its main aero engine business.

Akihiko Numazawa, general manager at IHI’s business development headquarters, notes that some of its existing business — given its heavy carbon dioxide emissions — could shrink significantly in as little as three years. Coal boilers, for example, generate just under 10 per cent of the company’s annual revenue.

“There is a strong sense of crisis among the management levels and that is why we want to change our business while we are still generating profits,” Numazawa explains.

But analysts say IHI’s ammonia technologies have not excited investors in the same way that the marketing of liquid hydrogen, by rivals such as Kawasaki Heavy Industries, has. “In the eyes of investors, it’s not doing any favours by not having any specific [financial] targets,” Citigroup bank analyst Graeme McDonald says. “Because they can’t quantify it, ammonia doesn’t get the attention that the company would like.”

But Edward Bourlet, an analyst at brokerage CLSA adds: “Ammonia relative to hydrogen has not been marketed or portrayed as effectively, and maybe that provides potential. IHI could be the dark horse of heavy industry.”