Receive free Architecture updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest Architecture news every morning.

The writer is the FT’s architecture critic

The Isle of Dogs was never an island but a peninsula, though it has often felt like one. It suited London’s docks to be separate, an isolated city of warehouses and wharves stuffed with valuable cargo. A place with a culture of its own. Transformed since the 1980s into a steely, glittering island of impenetrable global finance, it still feels apart, rich but precarious.

HSBC’s decision to vacate their 8 Canada Square Building — dubbed The Tower of Doom — for an office in the City is a shock to Canary Wharf. The upstart cluster with a Manhattan-style skyline, designed to supplant a flagging, pinstriped, class-bound Square Mile, is itself now struggling.

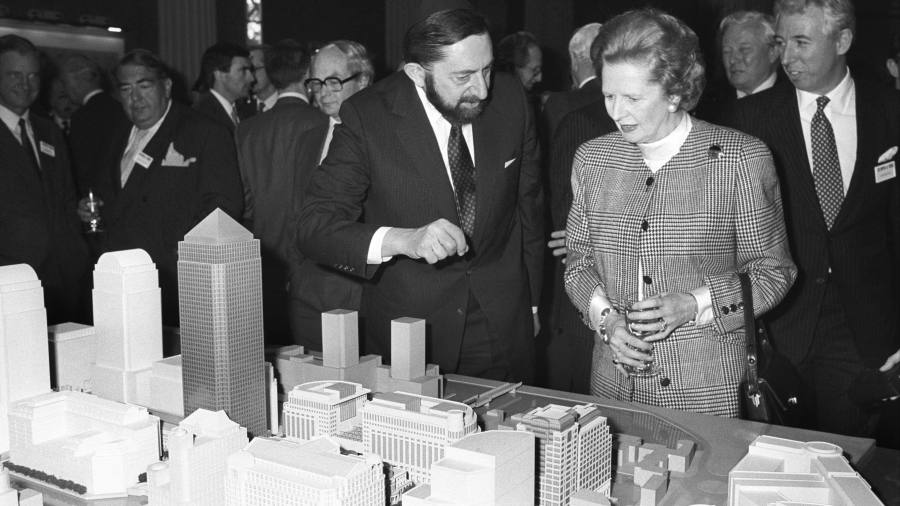

Canary Wharf was the result of a blend of Thatcherite politics, Big Bang deregulation and Michael Heseltine’s experiment with the London Docklands Development Corporation — a turbocharged privatisation and lightly regulated and untaxed development of public land. Canadian Developers Olympia & York were wooed by Thatcher, planning to do for Docklands what they had done for downtown New York with the World Financial Center.

But the WFC was only a few minutes walk from Wall Street. Canary Wharf was always out on its own — it even seems to have its own microclimate with hostile wind tunnels created between the skyscrapers. In fact there was plenty nearby; the Isle of Dogs one of the highest densities of council housing anywhere in England. But in the anti-social-housing Thatcher era, these were the wrong kind of neighbours. Rather than build a piece of connected, contiguous city, Canary Wharf became a moated, gated, privatised place, a symbol of division.

For a while it worked. The banks were seduced into new high-rise buildings. Olympia & York imported their favoured architects, César Pelli (designers of the towers in the NYC’s WFC) for the centrepiece One Canada Square with its distinctive pyramidal crown. SOM, the Chicago Modernists, masterplanned and built in a North American-style grid. Norman Foster, who had designed HSBC’s incredible Hong Kong HQ, at the time the most expensive building in the world, went to work on their London tower, a sleek extrusion. He then built the magnificent Jubilee Line Canary Wharf station, a perfect symbol of arrival, though now often looking uneasily empty.

The cluster of towers, now so prominent on the skyline, forced the City to transform; the reinvention was kick-started by Foster’s Gherkin, now subsumed by a huddle of taller, fatter towers. The precarity of Canary Wharf was underlined by Olympia & York’s bankruptcy in 1992, by the banking crisis of 2008 and then again by the pandemic. New development is virtually all residential, some very good, like Herzog & de Meuron’s One Park Drive, but most of it generic. Yet the area still somehow feels monocultural.

By the 2010s when the City proper had resupplied itself with high-grade office space, workers were drawn back to its pubs and alleys, pocket parks, bars and convivial lunch spots. The reinvention of Shoreditch was a lure while the hedgies went “up west” to Mayfair for proximity to clients and restaurants.

Canary Wharf is famed for its connectivity — first the Docklands Light Railway, then the Jubilee, then the Elizabeth Line, the £18.9bn cost of which was said to be the product of lobbying by bankers who wanted better Heathrow links. Its problem, however, is inherent in that very idea: it is defined by how easy it is to get in and out again. It was never truly part of London, billed as downtown Manhattan but more like La Défense or Olympia & York’s native Toronto, at best.

Its future is uncertain. The floor plates of those bank towers are too deep for conversion to residential and it remains isolated. Canary Wharf was a fascinating experiment. Now it needs to become, somehow, a part of its host city.