Receive free Bank of England updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest Bank of England news every morning.

Silvana Tenreyro gave her valedictory speech as an external member of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee yesterday afternoon. It was pretty on-brand. Here’s Reuters:

The Bank of England has no need to raise interest rates further to curb inflation, and risks having to make a sharp U-turn if it tightens policy any more, BoE rate-setter Silvana Tenreyro said in her last speech as an official at the central bank.

Tenreyro is, or was, the MPC’s most prominent dove (a title relative newcomer Swati Dhingra looks keen to inherit). That has not been a great thing to be lately.

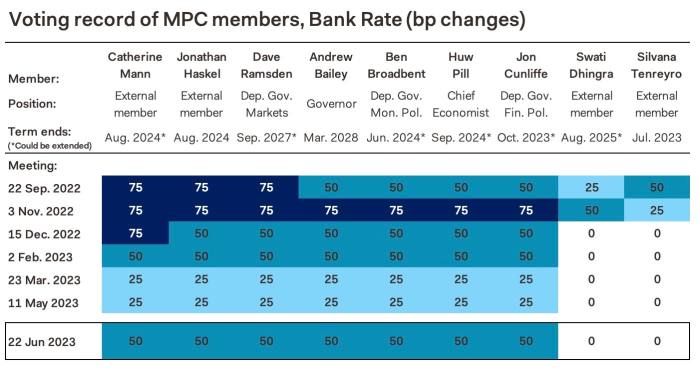

The Argentine economist hasn’t voted for a Bank Rate increase since last November — unsuccessfully backing holding rates for five meetings — and September 2022 will go down as the final time she was on the winning side in an MPC split. Chart via Pantheon Macroeconomics:

The rate holding is kinda odd. By repeatedly refusing to back increases, but also not calling for cuts, Tenreyro has in effect been endorsing each hike with a one-meeting delay.

Alphaville asked her about this in a post-speech Q&A (which can be watched here). She replied:

The policy stance is not just determined by the spot Bank Rate, it depends on the whole curve, right? As a member of the minority, I don’t get to choose the starting conditions. And so, I thought the best I could do is try to point to the path for the curve and be clear in communicating that I would expect a loosening will be needed to meet the inflation target. And the more we raise rates now, the earlier and faster I think we will need eventually to cut rates to meet the target. But again, the policy stance is not just Bank Rates.

It‘s not a very satisfying answer, but it spurred us to think about how Tenreyro’s record as a rebel compares with other MPC members. (Bear in mind it’s Friday.)

Using BoE data, we made some charts examining how the 47 different members the committee has had since 1997 have performed in terms of votes with or against the majority view. Caveats:

-

We’ve looked only at whether votes were with or against consensus, rather than the degree or direction to which they were against consensus

-

A lot has happened since 1997, so obviously members’ relative performance will obviously be reflect the macroeconomic particulars of their time on the MPC

-

Life is short so we’ve looked only at votes on Bank Rate, rather than those on asset purchases

-

This article is going to look better on desktop than mobile, sorry 🤷♂️

First up, here’s how many times each member has voted with consensus as a percentage:

As you can see, the current MPC is pretty spread across the spectrum: governor Andrew Bailey, deputy governor Ben Broadbent and chief economist Huw Pill have never been rebels, while Swati Dhingra has thus far never won a vote, making her from one perspective the MPC’s least successful member ever.

Other deputies Sir Jon Cunliffe and Sir Dave Ramsden are both slightly ahead of the average, while all the current external members are below.

Tenreyro, despite her recent notoriety for divergent dovishness, is statistically one of the most average MPC members ever in terms of raw hit rate.

What other nuggets can we glean? Lord Mervyn King is the only Bank of England Governor to have ever lost a vote, although of 14 turns on the losing side only two were when he was governor (he was previously chief economist). Sir Eddie George, Mark Carney and Andrew Bailey are all in the 100 per cent club.

There’s an obvious issue with the chart above: percentages don’t reflect varying tenures. This is obviously most prominent in the case of Charlotte Hogg, who was on the MPC for a single meeting before stepping down in 2017.

So here are the hits (votes with the majority) and misses (rebel votes) in raw number terms. If you click on the legend you can exclude hit or misses (doing the former reveals Danny Blanchflower rebelled 18 times, more than any MPC member before or since):

There’s a mildly interesting trend apparent here, with those members with a meeting-count in the middle of the pack tending go against consensus more often. Mildly interesting.

We’d suggest, looking at these numbers, that Adam Posen (now president of the Peterson Institute for International Economics) may have had the simplest tenure of any MPC member: 36 votes from 2009–2012, all of them to hold, all of them successful.

The strength of Broadbent — who we’ve previously dubbed the “centrist dad of British macroeconomic policymaking” — is also apparent here: since joining the MPC in 2011, he has gone a record 120 meetings without being in the minority a single time.

Is that reflective of a calmer period? Somewhat. The MPC has recently been its most divided since the financial crisis, but the first decade or so of independence was packed with split votes:

What does all this teach us? Not very much. But, as mentioned earlier, it’s Friday.