This month, Tim Woodcock will finally move into the house in Hove, East Sussex, that has, over a year and a half, been gutted and completely remodelled. With its open-plan layout and sleek modern look, this four-bedroom Edwardian semi has been transformed from its downtrodden days as part of a nursing home. Yet the works have taken their toll, lasting six months longer than planned and costing double the original budget.

Woodcock, 59, a business owner from Twickenham, south-west London, bought the property in the seaside town for £1.2mn in 2020 and set aside £350,000 for transforming it. “I spent £700,000,” he says. “About £100,000 of that was due to me being fussy at the end and over-speccing but the rest was down to inflation. The cost of materials, such as plasterboard, rose dramatically and tradespeople’s day rates went up by 30 or 40 per cent.”

Woodcock says the restored house is now worth about £1.7mn, £200,000 less than the combined spend. “I’ve finally got the home I wanted and it’s lovely being by the sea but a rising tide floats all boats and any fool can make money on property when the market’s going up,” he says. “If it’s falling and costs are rising, you’re going to get hurt.”

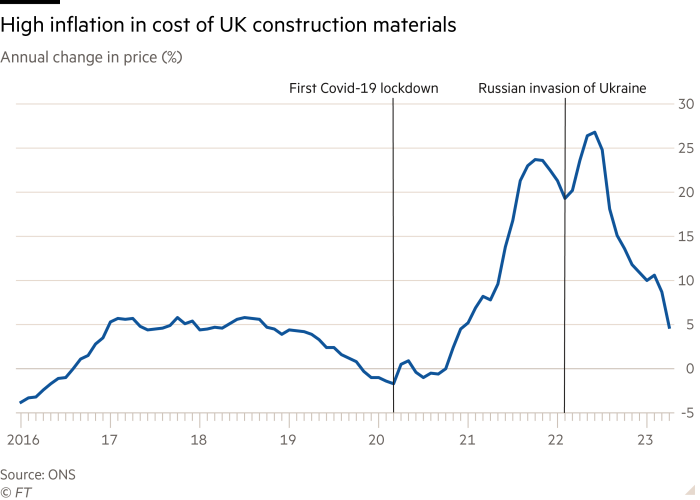

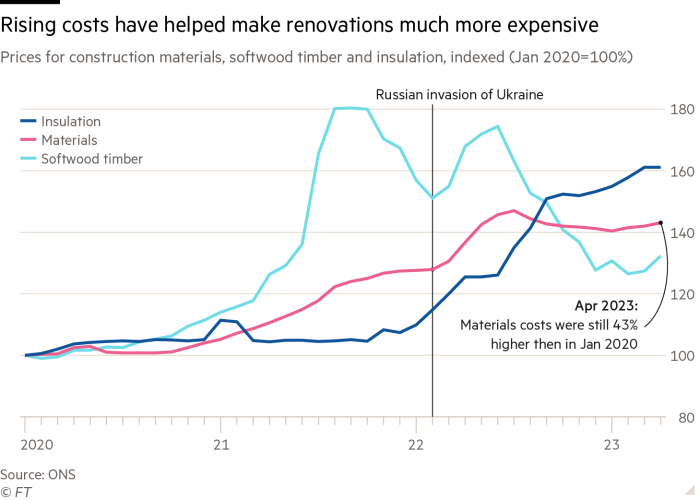

Rampant inflation, the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine have sent the cost of building materials through the roof and caused serious financial pain for homeowners doing building work.

Prices of construction materials in the UK in April were almost 5 per cent higher than the year before, according to the Office for National Statistics. And though materials price inflation is slowing from the peak seen in summer 2022, prices are now 43 per cent higher than they were in January 2020, before the pandemic hit, according to Professor Noble Francis, economics director at the Construction Products Association, using official data.

The spiralling costs of everything from concrete to insulating materials mean tradespeople have also been putting up their rates — in the first quarter of this year, three-quarters of members of the Federation of Master Builders reported an increase in the prices they charge. “This leaves homeowners with increased costs for new work and risks them putting off projects,” says Brian Berry, chief executive of the FMB.

Indeed, many architects and building companies report that homeowners are already pulling the plug on renovation works and extensions. “Rising costs have stopped many of my projects this year, with clients pausing because they decided they are not comfortable to embark on a project amid this uncertainty or because they mistakenly believe costs will go down when the rate of inflation slows,” says George Omalianakis, founder of the architecture firm GOAStudio London.

And, thanks to the combination of increasingly expensive works and rapidly rising mortgage rates, some people are pulling out of buying homes altogether.

Harry Hammonds, senior sales manager at Aston Rowe estate agency in Acton, west London, has recently had two sets of buyers decide not to buy properties that needed work: one because the build cost came in at almost double their estimate; the second because the quote they received for a loft extension when their offer was accepted rose dramatically in only three months. “The buyers pulled out just before exchange of contracts because the £75,000 estimate went up by £35,000 over that time,” Hammonds says.

So, as the numbers get increasingly difficult to stack up, is the dream of the fixer-upper on hold?

The overheated market during Covid, fired up by the stamp duty holiday and low mortgage rates, led to a boom in sales of homes that could be renovated or extended.

“There is typically around one home extension for every six house purchases and during the race for space more people were buying with the view of extending or improving,” says Frances McDonald, director of residential research at Savills estate agency.

The number of homes granted full planning permission hit a peak of 339,473 in the year to June 2021, according to Savills’ figures. However, since then rising costs mean there has been a steady decline in the number of people seeking to overhaul their homes.

Savills says consents fell to about 255,000 in the 12 months to March 2023 and may well reduce further — its analysis of data from the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities shows the number of applications submitted in 2022 was 14 per cent lower than in 2021.

Materials shortages have had an impact on those braving renovations — Woodcock, for instance, had to wait a year for the parts for the mechanical ventilation with heat recovery system to come from China. And though some of these backlogs have now eased, anyone embarking on a fixer-upper has struggled to find tradespeople. “Certain builders I know in Bristol have a two-year waiting list, while even a delay of a few weeks for securing a good plasterer might have an impact,” says Jerome Lartaud, director of Domus Holmes Property Finder.

Although demand for builders was exacerbated by those who sought to extend their existing home during the pandemic rather than brave a highly competitive housing market, the dearth of skilled workers is a longstanding problem in the UK that has been compounded by Brexit and is most acute in London and the south-east of England, according to Berry at the FMB. “The availability of EU workers, who made up 9 per cent of the overall construction workforce, is no longer a viable option,” he says, adding that a lack of skilled tradespeople delayed jobs for nearly half of FMB members in the first three months of this year.

And there is another roadblock in the form of the planning system, with staff and skills shortages in council planning departments meaning householder applications are unlikely to be decided in the target eight weeks. “For anyone embarking on a project, there are likely to be severe delays at the planning stage, with many councils and London boroughs struggling to meet their deadlines,” says Amrit Marway, associate director at Architecture for London. Many architects are reporting that delays are now extending to six months or more.

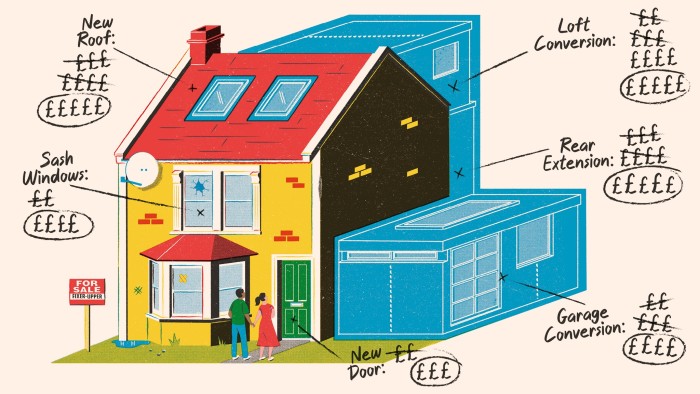

Home improvement works are now significantly more expensive than they were before the pandemic. Marway says tenders for a loft conversion for an average London terraced home are now coming back at £100,000, compared with £75,000 before Covid, while a kitchen extension of roughly 30 sq m now costs about £110,000, up from £75,000 in 2019. Even a small project, such as a downstairs toilet, has become vastly more expensive in the past three years, from an estimated £5,000 to £8,000, an increase of 60 per cent.

Homeowners are also finding that in the time between getting an estimate for major building works to receiving a final detailed quote — often a process that can take six to nine months — costs can rise quite significantly. A client of Omalianakis’s who was recently seeking to refurbish a top-floor flat in Camden, north London, and add a large extension saw the final quote rise 10 per cent from the initial estimates six months earlier to almost £140,000. “The rising cost is a boiling-a-frog scenario, a gradual thing that every day, every week, every month, gets worse and affects more people,” Omalianakis says.

Homeowners in London now need on average to add an extra 20 per cent to their renovation or extension budget compared with pre-Covid, according to Alice Barrington-Wells, partner at the design and build company Carter Wells. “You also have to consider that most of the companies involved in a renovation have had to increase their own fees and profit margins as well to stomach interest rates and the financial aftermath of Covid — so it’s not only the cost of contractors that has risen but it has for architects and interior designers too,” she says.

For some people whose homes need work, the double shock of rising mortgage rates and the increased cost has meant adjusting their aspirations quite significantly. Lucy, who did not want to give her real name, bought a two-bedroom terraced house in east London in 2021, taking out a two-year fixed-rate mortgage. The property had planning approval for an extension but last year, when costs started rising rapidly, she and her husband pressed pause.

“We have two children, so it’s a bit of a squeeze without the extension but we couldn’t make the sums work any more,” says Lucy, 38, who works in marketing. “We also have to remortgage soon and will see our monthly payments treble, so have decided we will reduce the project quite drastically, move a few walls and live within our means for now.”

Estate agents say many buyers are now avoiding properties that need work because, when you factor in high stamp duty and other purchasing costs, fixer-uppers are no longer financially viable — especially in expensive markets such as London and the South East.

“Five years ago, homeowners might have added 10 to 20 per cent to a London home’s value by buying an unmodernised property and doing it up,” says Henry Sherwood, managing director of The Buying Agents. “These days, if you’re lucky, it will only be worth the sum of its parts — the purchase price plus the refurb.”

As a rule of thumb, Marway says that in the current market a dilapidated house in London should be priced at least £3,500 per sq m lower than the market rate for similar properties completed to a high standard. “This should allow scope for refurbishment inclusive of all costs,” she says.

Yet finding properties below market value is a huge challenge. “Everyone dreams of finding somewhere with orange walls and an avocado bathroom suite but they are becoming rarer and rarer,” Sherwood says. Buyers have increasingly turned to auctions — in 2022, Savills Auctions sold a record £455mn worth of property — but this route has traditionally been favoured by cash buyers, even more so now that mortgage rates have risen so dramatically.

The stamp duty holiday didn’t only fire up homeowner renovations — it also stoked a surge in flipping, or buying a property to sell quickly for a profit. Last year, 26,340 homes in England and Wales were bought and sold within 12 months, the highest number since 2007, according to analysis by Hamptons estate agency. Of the homes flipped in 2022, 44 per cent were bought between January and October 2021, during the stamp duty holiday.

“Many of these flippers were able to capitalise on the strong house price growth post-Covid,” says Aneisha Beveridge, head of research at Hamptons, who adds that house flippers in 2022 saw record cash returns, selling their properties for an average of £42,800 more than they paid.

Yet the slowing property market has put the brakes firmly on flipping for all but the most seasoned property investors. “Flippers have all the cost and delay pressures faced by those renovating their own homes plus the 3 per cent stamp duty surcharge [levied on additional properties] and the added stress of needing to renovate and sell within a tight timeframe,” says Charlotte Strang, director of Strang & Co Property Search. “Even if you can do the works in three to six months, it can take you six months to go through conveyancing at the best of times and, in the meantime, you have finance costs going up and up.”

Some of those looking to flip are changing tack and homing in on cheaper areas. “Friends who have done it successfully, selling a house in south-west London every 18 months, are now looking to the north-east of England,” says Mark Parkinson, managing director at Middleton Advisors. The buying agency recently released a research report revealing that the optimum holding period for private housing is nine years if losses are to be avoided — meaning the odds are stacked firmly against those buying and selling in a short timescale.

Meanwhile, some would-be renovators may now be waiting on the sidelines for property prices to drop and for inflation to fall back. Consultancy Capital Economics expects inflation to ease next year, allowing interest rates to be cut from mid-2024, with total house price falls of about 12 per cent. Yet, even though the costs of labour and building materials are predicted to stabilise, experts warn that it is unlikely they will come down to pre-pandemic levels, even with an adjustment for inflation.

A few renovators are pressing on regardless. Carly Anderson, 41, a former civil servant from Belfast, has agreed to buy two rundown properties she is planning to fix up this year and sell on quickly — her quest helped significantly by the fact average values in the city are still 20 per cent below their 2008 peaks, according to Zoopla.

Whatever money Anderson makes will go towards building her own home, a detached five-bedroom house in south Belfast. “It’s going to have an open-plan kitchen-diner, a walk-in wardrobe, an outbuilding with my office and a gym,” she says. “I’m also trying to squeeze in a city pool but I’m fussy and there’s always something I’d like to change.”

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @FTProperty on Twitter or @ft_houseandhome on Instagram