The Upper Tantallon wildfire began on a beautiful, hot Sunday afternoon.

The date was May 28. Many residents were away from home, maybe at the beach or with loved ones, and were likely checking their phones less than usual.

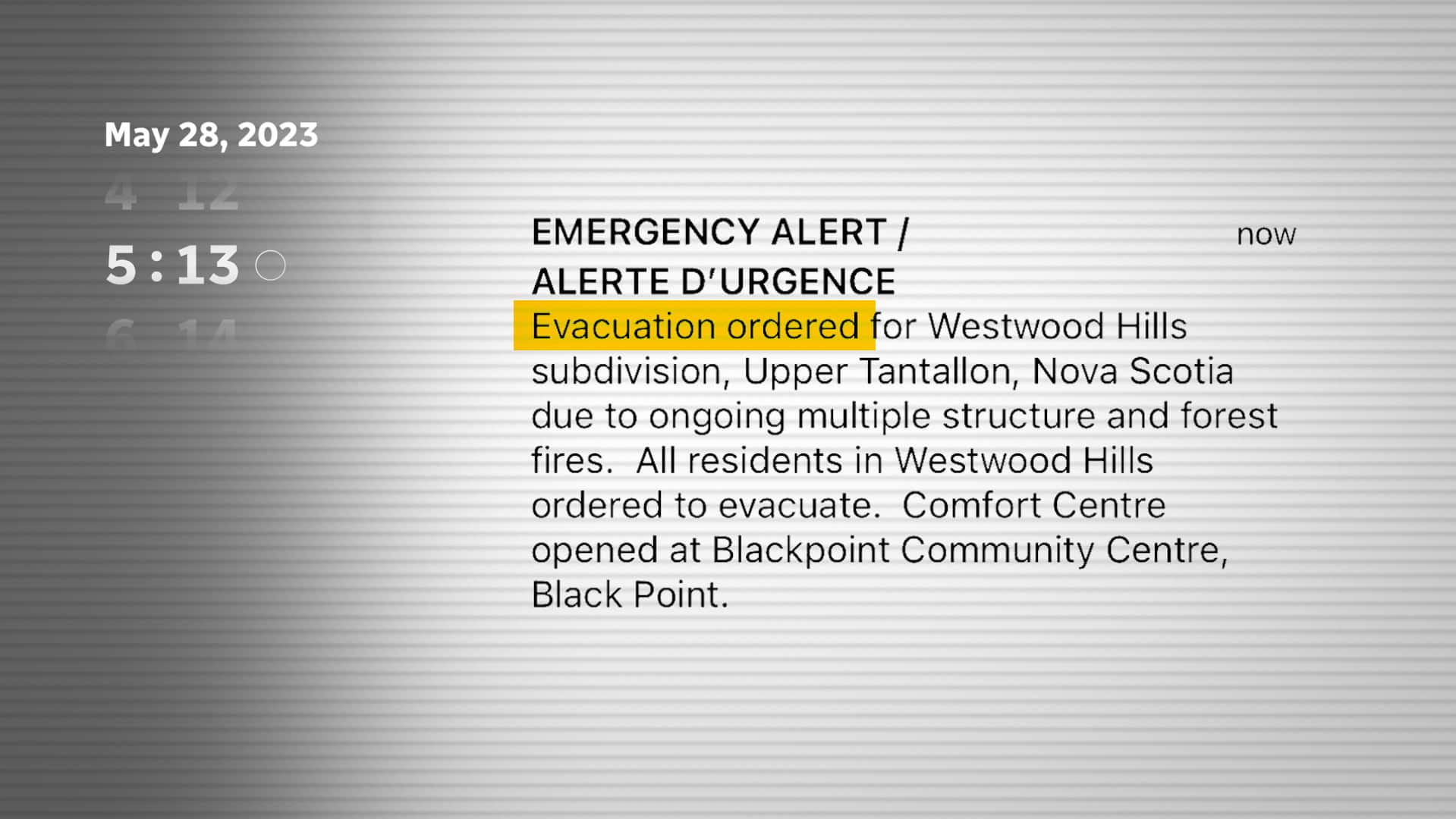

By the time an emergency alert was issued at 5:13 p.m., telling residents of Westwood Hills to evacuate, homes in the subdivision had been burning for more than an hour and a half.

“Honestly, I would say it’s slow,” said Erica Fleck, director of emergency management for the municipality, about the gap.

“But again not having all of the data and looking at it, you know … we’d have to verify that, obviously.”

CBC News has constructed a timeline of how the first few hours of the wildfire unfolded, with information from Halifax Regional Municipality, the provincial Emergency Management Office (EMO) and Nova Scotia RCMP.

The slowness of the first emergency alerts on May 28, 2023, reminded some of the panic during the mass shooting of 2020. CBC News has constructed a timeline of how the first few hours of the wildfire unfolded.

The fire led to evacuation orders for about 16,400 residents — stretching from Upper Tantallon to Sackville — and destroyed 151 homes.

Police respond to call for help

At 3:29 p.m., RCMP were called to help Halifax Fire fight a blaze that was spreading in the woods near Juneberry Lane in Westwood Hills.

Sometime between then and 3:40 p.m., officers began going door-to-door telling residents to leave.

At 4 p.m., RCMP posted messages on their Facebook and Twitter pages asking Westwood residents to immediately evacuate their homes along a certain route — but they used the wrong street name. The post also said an emergency alert from the Emergency Management Office would be issued “imminently.”

That did not happen.

Spokesperson Cpl. Chris Marshall said the posts were deleted on June 1 to “avoid confusion” because the municipality had been making frequent posts about evacuations “and the information in the tweets were no longer current.”

When asked why RCMP could not have issued their own alert, since they have that power, Marshall said they only do so for police-led incidents, not “natural disasters” like a wildfire.

Fleck learns of fire

Sometime between 4:30 p.m. and 4:45 p.m., Erica Fleck, director of emergency management for the municipality, said she first heard sirens while enjoying the sunshine on her deck.

Fleck said she ran into her house to check her phone and began making calls to deputy fire chiefs and CAO Cathie O’Toole to find out what was happening, then headed to the emergency operations centre.

“And then you know, got the first call that, ‘OK, we need to evacuate.’ So then we started to do an alert right then,” Fleck said.

EMO sends first alert

At 5:05 p.m. the provincial Emergency Management Office received the wording for the first Alert Ready message from Fleck telling Westwood Hills residents to evacuate.

It was sent eight minutes later, at 5:13 p.m., to most cell phones, TVs and radios — an hour and 44 minutes after police responded to the fire call.

Three more alerts followed for nearby areas as the fire spread: at 6:09 p.m., 7:41 p.m. and 10:19 p.m.

It’s unclear whether Halifax Fire staff began attempting to contact Fleck before she picked up her phone at around 4:30 p.m.

Deputy Chief Dave Meldrum of Halifax Fire said in an email the department has no timeline information to share while they conduct an internal post-incident review.

“That process is ongoing and will require some time to complete,” Meldrum said.

Marion Gillespie was one of many residents who found out about the fire on Sunday afternoon through word of mouth or social media.

Gillespie and her husband rushed to get back into their home in Highland Park, which is about four kilometres from Westwood. She said they assumed they would be impacted, and arranged to get their pets out with friends long before the evacuation order for their subdivision was sent at 6:09 p.m.

When that alert did go out, the Gillespies had just been turned around on Hammonds Plains Road by police. Flames and smoke surrounded their car, and Gillespie said “we were just terrified that we were going to lose our lives.”

She said if the issue was reaching Fleck in order to send the alert, there should be a second person that has issuing power — and if they can’t be reached, then a third person, and so on.

“It all came too late. Way too late. And it’s not one person’s fault,” Gillespie said.

“EMO is a group, the municipality, they all have a say in all of this and so you can’t point a finger at one person. It’s a group effort and they failed.”

After-action report expected by August

The gap between the wildfire breaking out and evacuation information being relayed brings to mind the province’s mass shooting in April 2020, when residents were left scouring social media for details about the whereabouts of a gunman in a mock police cruiser.

The final report from the Mass Casualty Commission recommended that “police and emergency services agencies should ensure that public warnings reach as many community members within an at-risk population as possible.”

Fleck said she and her emergency management staff, and all those within the city’s new community safety unit, have read the report and are “very cognizant” that alerts need to be timely.

They have just begun gathering information for the city’s own after-action review, Fleck said, and have yet to sit down with Halifax Fire, police or other agencies to go over exactly how the day unfolded.

Her team is still in “recovery” mode helping residents affected by the blaze, Fleck said, and expects the entire post-mortem to be done by mid-August.

That report will eventually make its way to city council.