After Alberta experienced its deadliest month on record for opioid deaths, some health researchers are calling for the province to return to releasing neighbourhood-level data, arguing that doing so could help save lives.

But the provincial government isn’t committed to doing so yet, telling CBC News in an email that there are concerns tied to privacy.

Elaine Hyshka is the Canada Research Chair in health systems innovation at the University of Alberta’s School of Public Health. She said researchers are often waiting on the province to release timely data, even though numbers started to climb around 2015.

“People on the ground are really flying blind when it comes to who is dying. Where are they dying? What kinds of programs and services can we be putting in place in those specific areas to immediately save lives?” Hyshka said.

“There’s just no way to do that without access to information. So I hope the government will commit to following the lead of British Columbia and release those data monthly.”

Neighbourhood-level data in Edmonton and Calgary and trends in the spatial distribution of overdose in the other major cities around Alberta used to be accessible by researchers but isn’t any longer.

The province also hasn’t released reviews of medical examiner data tied to opioid-related deaths for years, the last one being tied to 2017 data.

That report involved reviews of every death, the jobs they worked, their history of incarceration, and more, Hyshka said.

“These factors would then point to areas of the system where we should be focusing, right? So if we see, for example, there’s a lot of people who are leaving incarceration that are dying, then we would focus on enhancing programs within carceral settings,” she said.

“We haven’t had that review done since 2017. B.C. has done at least two since then. So that’s one thing I’d like to see.”

Provincial response

Various organizations have called for changes around how opioid data is reported in Alberta.

In February 2022, the Edmonton Zone Medical Staff Association said it had twice requested local geographical area data for deaths related to opioid poisoning and calls made to EMS, but it hadn’t received responses.

When it came to these most recent calls for updates, Hunter Baril, a spokesperson with the province, said Alberta’s substance use surveillance system is more comprehensive than what was previously contained in opioid surveillance reports.

“Although local geographic data is used to inform decisions around necessary supports and services, neighbourhood-level data is not released publicly to protect the privacy of Albertans and prevent stigmatization of those struggling with addiction,” he wrote in a statement.

Hyshka said it would be possible to release the data without impacts to privacy, adding the government routinely published it until the end of 2020.

“All these data do is tell us where people are dying. I think the goal of efficiently targeting life-saving interventions outweighs any abstract concerns related to ‘neighbourhood stigma,'” Hyshka said in an email.

“In fact, I think the maps help show that these fatalities occur across cities and that no neighbourhood is immune.”

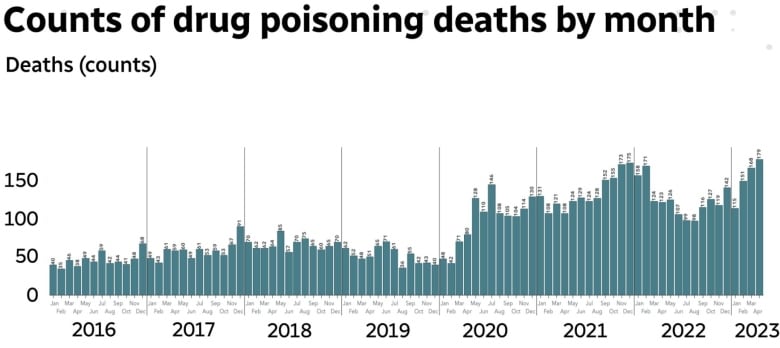

Alberta poisoning deaths in April due to opioids hit 179, the highest number since the province started collecting data in 2016, according to the province’s substance use surveillance system. The numbers were updated on Monday.

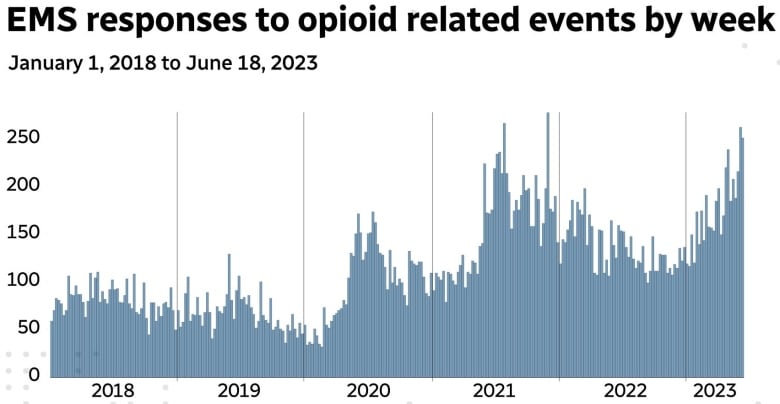

Weekly EMS responses to opioid-related emergencies have also been growing in frequency this year, with the weeks of June 5 and June 12 being the third and fourth highest on record, respectively.

View from street-level group

Samantha Ginter is the program co-ordinator of the Alberta Alliance Who Educates and Advocates Responsibly (AAWEAR) chapter in Red Deer. She said neighbourhood-level data would provide value — if the privacy of those who were using substances was protected.

AAWEAR conducts street outreach, which involves face-to-face work with people living on the streets.

“I do think there are benefits to releasing this information to organizations that work front lines, as a way to know where supports are needed most,” she said.

Privacy considerations exist, but it’s difficult for neighbourhoods to target response strategies right now given the data available, according to Kathryn Dong, an associate professor in the department of emergency medicine at the University of Alberta.

“There will be areas that we can’t report in great detail due to low numbers,” she said.

“But I do think that we should be able to find a compromise in terms of respecting privacy and confidentiality and not stigmatizing certain neighbourhoods, but also giving communities access to information that will help them locally respond to what they’re seeing.”

Hyshka and Dong also said more information should be released publicly about the effects of the provincial government’s strategies around addressing the opioid crisis, such as the impacts of new addiction treatment beds and the Digital Overdose Response System (DORS) app.

Since being launched last year, the DORS app has seen about 1,600 individuals registered, with around 250 unique individuals that have utilized it, meaning they have started a session, according to Baril.

This has resulted in 110 contacts with the STARS emergency centre and 24 emergency responses, he said.

The province didn’t respond by publication time to specific queries on how many people were currently waiting on beds, how many people accessed treatment last year, and how many people completed treatment in 2022.