A complex combination of factors could be responsible for the pediatric hepatitis cases that have been puzzling doctors in recent months, according to two small, new studies.

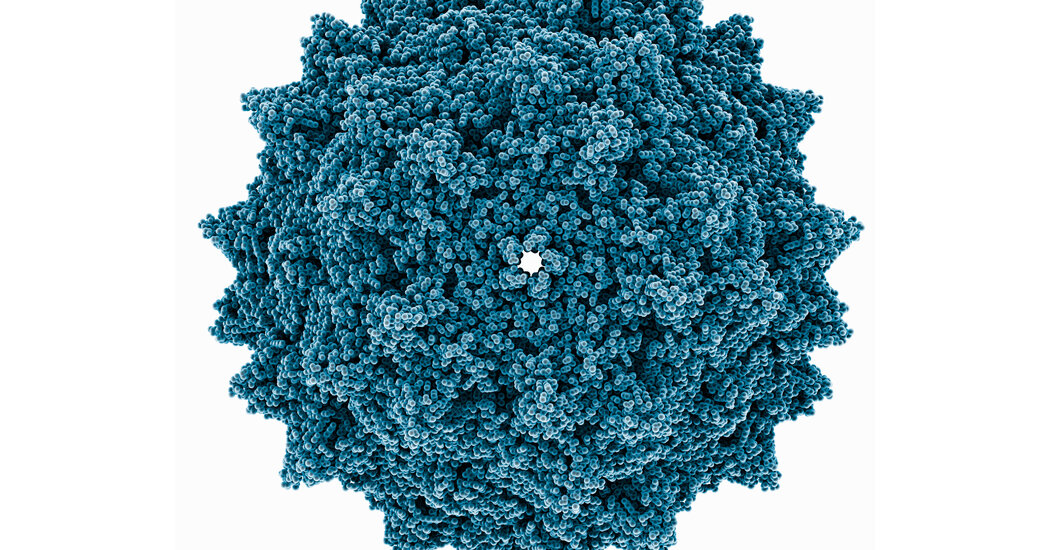

The studies are based on just a few dozen cases and have not yet been peer-reviewed or published in scientific journals. Still, they suggest that the children who have developed severe, unexplained cases of liver inflammation may have been simultaneously infected with two different viruses, including one known as adeno-associated virus 2 (A.A.V.2), a typically benign virus that requires a second “helper” virus in order to replicate.

Adenoviruses, which have previously been found in many of the children with the mysterious hepatitis reported within the last year, are common helper viruses for A.A.V.2.

Many of the children studied also had a relatively uncommon version of a gene that plays an important role in the immune response, the scientists found.

Together, the findings suggest a possible explanation for the hepatitis cases: In a small subset of children with this particular gene variant, dual infections with A.A.V.2. and a helper virus, often an adenovirus, trigger an abnormal immune response that damages the liver.

Still, the researchers acknowledged that the studies are based on a small number of children in just one region of the world (the United Kingdom) and that a causal link had not been proven.

“There’s a lot that we still don’t know,” said Dr. Antonia Ho, a clinical senior lecturer at the MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research and an author of one of the new studies.

But, she added: “We felt — because there’s been very little in the way of answers of what are the causes — that we needed to release these findings so that other people can start looking for A.A.V.2. and investigate this in more detail.”

The findings are intriguing but preliminary, said Dr. Saul Karpen, a pediatric hepatologist at Emory University and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, who was not involved in the research. “This is not a definitive study,” he said. “Thematically, it certainly can make sense, but there is not full support for it.”

The pediatric hepatitis cases are exceedingly rare but can be severe. As of July 8, 1,010 probable cases had been reported from 35 countries, according to the World Health Organization. Five percent of those children have required liver transplants, and 2 percent have died.

Several early studies have found that many of the children were infected by an adenovirus, one of a group of common viruses that typically cause cold or flulike symptoms. The new studies suggest that if adenoviruses are involved in the hepatitis cases, they may just be part of the story.

In one of the new studies, scientists compared nine Scottish children with unexplained hepatitis to 58 children in control groups. The researchers used genomic sequencing to identify any viruses present in blood, liver and other samples from the children.

The scientists found adeno-associated virus 2 in the blood of all nine affected children and in liver samples from all four of the children from whom such samples were available. They also found an adenovirus in six of the children and a common herpes virus in three.

On the other hand, the researchers did not detect A.A.V.2 in healthy children, in children who had adenovirus infections but normal liver function or in children who had hepatitis with a known cause.

Those findings are consistent with those from a second study, led by researchers in London, which examined samples from 28 children with unexplained hepatitis from across the United Kingdom. That scientific team also found high levels of A.A.V.2 in the blood and livers of many of the children. Many also had low levels of an adenovirus or herpes virus in their samples.

The Scottish researchers also found that eight of the nine affected children, or 89 percent, shared a relatively uncommon variant of a gene that codes for a critical protein in the body’s immune response. This particular variant is present in just 16 percent of Scottish blood donors.

The London team found the same gene variant in four of the five transplant recipients they assessed.

“Both studies have reached independently, remarkably similar results,” Sofia Morfopoulou, a computational statistician at the Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health at University College London and an author of the second paper, said in an email.

Although the idea remains preliminary, it is possible that a recent resurgence of the adenovirus after a decline in circulation during the coronavirus pandemic, explains why doctors have noticed a sudden spike in these rare cases, the scientists said.

“Perhaps some of these infections that might have occurred in a more spaced out way, over a couple of years,” are instead occurring all at once, said Dr. Emma Thomson, an infectious diseases physician at the Centre for Virus Research and a senior author of the Scottish study.

Additional, larger studies are still needed, particularly focusing on children in other countries, the researchers said.