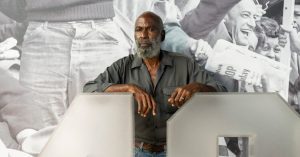

Rochester researchers used fruit flies as model organisms to study Segregator Distorter (SD), a selfish genetic element that skews the rules of fair genetic transmission. Credit: University of Rochester photo / J. Adam Fenster

Biologists from University of Rochester used population genomics to study a selfish ‘supergene’ that skews genetic inheritance.

“Selfish genetic elements” litter the human genome. They do not seem to benefit their hosts but instead seek only to propagate themselves.

These selfish genetic elements can wreak havoc. For example, they can distort sex ratios, impair fertility, cause harmful mutations, and even potentially cause population extinction.

Biologists have for the first time used population genomics to shed light on the evolution and consequences of a selfish genetic element known as Segregation Distorter (SD). These researchers at the University of Rochester, include Amanda Larracuente, an associate professor of biology, and Daven Presgraves, a University Dean’s Professor of Biology.

In a paper published recently in the journal eLife, the scientists report that SD has caused dramatic changes in chromosome organization and genetic diversity.

A genome-sequencing first

The scientists used fruit flies as model organisms to study SD, a selfish genetic element that skews the rules of fair genetic transmission. Fruit flies actually share about 70 percent of the same genes that cause human diseases, and because they have such short reproductive cycles—less than two weeks—researchers are able to create generations of the flies in a relatively short amount of time.

As expected under Mendel’s laws of inheritance, female flies transmit SD-infected chromosomes to about 50 percent of their offspring. However, males transmit SD chromosomes to nearly 100 percent of their offspring, because SD kills any sperm that do not carry the selfish genetic element.

How does SD do this?

Because it has evolved into what researchers refer to as a “supergene”—a cluster of selfish genes on the same chromosome that are inherited together.

Scientists have known for decades that SD evolved to form a supergene. But this is the first time they have used what is known as population genomics—examining genome-wide patterns of DNA sequence variations among individuals in a population—to study the dynamics, evolution, and long-term effects of SD on a genome’s evolution.

“This is the first time anyone has sequenced the whole genomes of SD chromosomes and therefore been able to make inferences about both the history and the genomic consequences of being a supergene,” Presgraves says.

An evolutionary downfall on the horizon

The advantage of being a supergene is that multiple genes can act together to cause SD’s near-perfect transmission to offspring. As the researchers found, however, there are major drawbacks to being a supergene.

In sexual reproduction, chromosomes from the mother and the father swap genetic material to produce new genetic combinations unique to each offspring. In most cases, the chromosomes line up properly and crossover. Scientists have long recognized that the exchange of genetic material by crossing over—known as recombination—is vital because it empowers natural selection to eliminate deleterious mutations and enable the spread of beneficial mutations.

As the researchers showed, however, one of the major costs of SD’s near-perfect transmission is that it does not undergo recombination.

The selfish genetic element gains a short-term transmission advantage by shutting down recombination to ensure it gets passed on to all of its offspring. But SD is not forward-looking: preventing recombination has led to SD accumulating many more deleterious mutations compared to normal chromosomes.

“Without recombination, natural selection can’t purge deleterious mutations effectively, so they can accumulate on SD chromosomes,” Larracuente says. “These mutations might be ones that disrupt the function or regulation of genes.”

The lack of recombination may also lead to SD’s evolutionary downfall, Presgraves says.

“Due to their lack of recombination, SD chromosomes have begun to show signs of evolutionary degeneration.”

Reference: “Epistatic selection on a selfish Segregation Distorter supergene – drive, recombination, and genetic load” by Beatriz Navarro-Dominguez, Ching-Ho Chang, Cara L Brand, Christina A Muirhead, Daven C Presgraves and Amanda M Larracuente, 29 April 2022, eLife.

DOI: 10.7554/eLife.78981