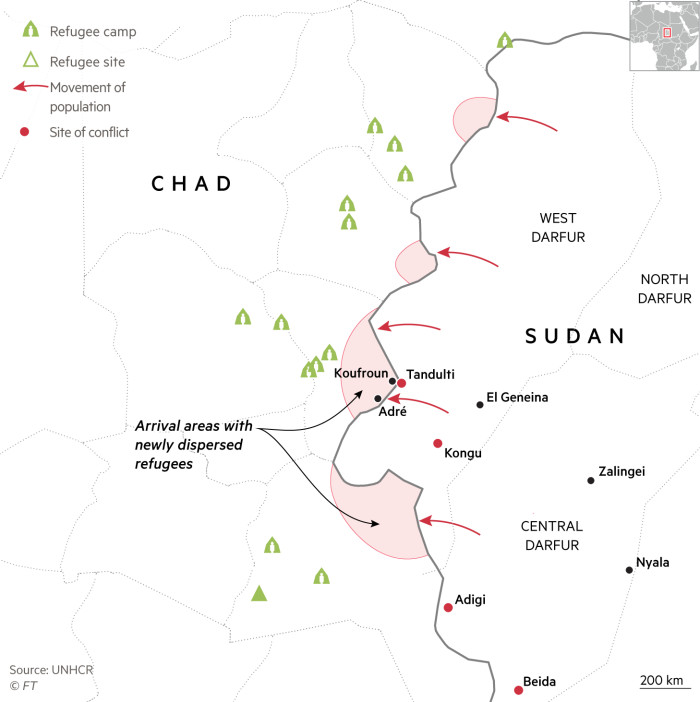

Across dry riverbeds, tens of thousands escaped to Chad, fleeing war in Sudan and a name that evokes terror for many: Janjaweed, the “evil on horseback”.

“They came on horses,” cried Djamila Ibrahim, carrying her six-month-old baby in the border Chadian village of Koufroun. “Some wearing khaki fatigues, with machine guns, shooting everywhere, everyone, and they killed my 14-year-old daughter.” Her brother and his three children also died in the assault.

Ibrahim was among 85,000 people who fled El Geneina, capital of West Darfur and the scene of some of the worst violence since fighting broke out in Sudan in mid-April.

Marauding fighters on camels, horses and trucks pillaged the city following battles between the Sudanese armed forces and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces. “The problems of Khartoum came to Darfur,” Ibrahim said.

The bloodshed has marked the return of the militias who wreaked havoc across Darfur, reigniting a two-decade-old conflict. More than 380 civilians have been killed in Darfur in recent weeks, according to a Sudanese doctors’ association.

The spark has been conflict in Khartoum that has pitted forces led by Sudan’s de facto president and army chief General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan against the paramilitary RSF of General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, better known as Hemeti. The vast and largely deserted Darfur region is familiar to both.

Burhan climbed through the army ranks while fighting rebels in Darfur who rose up against the Arab-dominated government of former strongman Omar al-Bashir in a brutal war that started in 2003 and cost about 300,000 lives.

Hemeti, who is originally from a Chadian-Arab clan in North Darfur, was commander of a Janjaweed brigade that fought on behalf of Bashir. The International Criminal Court later charged the former president with genocide and some Janjaweed commanders — although not Hemeti — with war crimes.

If the army succeeds in pushing the RSF out of Khartoum, Hemeti and his men are expected to use Darfur as a place to regroup and rearm. “If Hemeti wins Khartoum, the RSF will try to cement control of Darfur, which will embolden Arab militias, who are desert warriors that will stop at nothing,” said a senior humanitarian aid official in Chad.

“If he loses Khartoum, he’ll fall back into Darfur to establish his base. Both scenarios are terrible for Darfur . . . Darfur will be the garden of war for the powers of Khartoum.”

Despite repeated peace attempts, bouts of violence have continued for years in the area, with fighters raiding, torching and looting villages in a conflict in which Arabs — particularly those Rizeigat who became part of the Janjaweed militia — battled against the Darfur tribes, including the Masalit.

“Ongoing attacks have included unlawful killings, beatings, sexual violence,” said Tigere Chagutah, Amnesty International’s head for east and southern Africa. “Today, Darfur’s civilians remain at the mercy of the same security forces who committed crimes against humanity and war crimes in Darfur.”

Nasr Aldin Adam, a pro-democracy activist in El Geneina, said he feared the situation would only deteriorate if the RSF were driven out of Khartoum to regroup in Darfur.

“They have community support in some areas. El Geneina is a strategic area for them if they want to get support or back-up from other countries,” he said. “That will be a big problem for civilians in Darfur, all of us here know well what they can do — killing, looting.”

While global attention focused on the fighting in Khartoum, the violence has aggravated Darfur’s deep-rooted divisions, a situation that one western diplomat in N’Djamena said had parallels with the outbreak of inter-ethnic bloodshed in 2003.

Human Rights Watch in May noted a surge in fighting between militia members from the ethnic Masalit and Arab communities in El Geneina. The UN has recently reported clashes in Zalingei in Central Darfur, Nyala in South Darfur and El Fasher in the north of the province, and said fighting in El Geneina had escalated into “deadly ethnic clashes”.

Jérôme Tubiana, a former member of the UN Panel of Experts on Sudan, said: “What is happening between Arabs and Masalit in West Darfur is a continuation of outbursts of violence that took place regularly before this latest conflict. The security vacuum can only make things worse.”

The RSF has said it now controls half of El Geneina and most of the key cities of Nyala and El Fasher. One RSF officer claimed Sudan’s military had handed weapons to the Masalit to fuel “civil war”. “It’s not RSF against the military, it’s tribes fighting each other, but most of the RSF fighters are from Darfur,” he said.

Ali Mahamat Sebey, mayor of the Chadian border town of Adré, said he feared a wider conflict as cross-border ethnic loyalties could rapidly draw people from Chad and the Central African Republic into a war in Darfur.

After decades of bloodletting, there is little hope of respite for the people of Darfur. Madina Gamar fled Tandulti at the Sudanese border last week after the village was attacked, with armed men even killing people who had crossed into Chad.

“The Janjaweed came unexpectedly and started shooting everyone,” she said, comparing it to the trauma of her childhood, when armed men shot her parents and her younger sister in 2003. “I am tired of Darfur always being at war,” she said.