Gilberto thought he knew pain until he experienced the agony of withdrawal from xylazine, an animal tranquilliser used as a cutting agent in the more lethal drugs supplied by cartels to addicts in America.

“I’ve been shot before and beaten but this really makes me cry,” said Gilberto. The 44-year-old homeless drug user trembles as he points to deep wounds on his legs that are trademark signs of injecting the powerful sedative also known as “tranq”.

Gilberto is one of hundreds of people suffering from substance use disorder who live a chaotic existence in Kensington, a rundown neighbourhood in northern Philadelphia where addicts buy and use drugs openly on the streets. The area is ground zero in an overdose crisis sweeping the US that is driven primarily by fentanyl.

The synthetic opioid, 50 times stronger than heroin, was linked to more than two-thirds of the record 109,680 overdose deaths in the US last year — the equivalent of one fatality every five minutes.

US demands to crack down on cross-border trafficking of fentanyl have caused a rift with Mexico, where some of the most powerful cartels are based. Those cartels are now adding xylazine to drugs including fentanyl to boost profits by supplementing them with a low-cost high — creating a new and deadly threat to US public health.

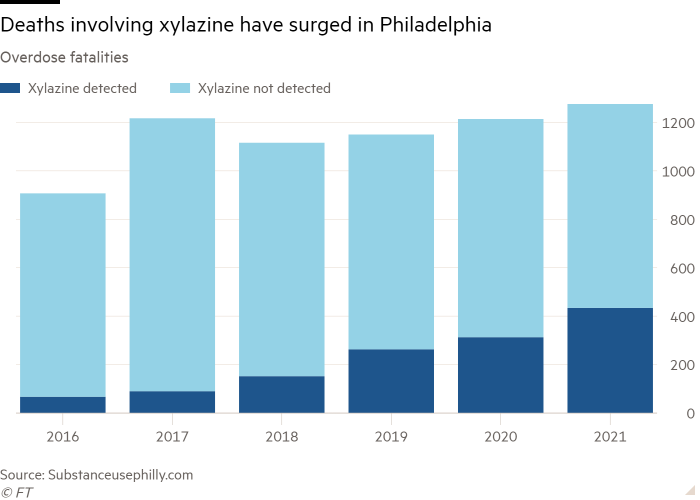

Over the past 18 months authorities have tracked a surge in the number of xylazine-positive overdoses, which are harder to treat than fentanyl-only overdoses because the drug has never been approved for human use and no antidote has been developed. In Kensington, charities set up to assist addicts with recovery or dress wounds cannot cope with the surge in cases.

“This is a matter of urgency and life depends on it,” said Rahul Gupta, the White House’s drugs tsar.

Health experts say xylazine, which is typically used by vets to sedate horses and cattle, can cause pus-oozing lesions, which when left untreated can lead to limb amputations. Many users say they do not know they are consuming the drug, which appears to have been first mixed into heroin in Puerto Rico almost two decades ago.

“It causes people to rot from the inside out,” Jamill Taylor, inspector at Philadelphia police narcotics unit, told the Financial Times.

The number of fatal overdoses involving xylazine in Philadelphia increased from 15 in 2015 to 434 in 2021 — a third of all fatal overdoses, according to health officials, and 90 per cent of the city’s illicit opioid supply is now adulterated with the animal tranquilliser.

“This is escalating so rapidly. We need new resources,” said Jeanmarie Perrone, founding director of Penn Medicine Center for Addiction Medicine and Policy.

Taylor said drug gangs had realised that cutting xylazine into fentanyl can maximise profits. A kilogramme of xylazine powder can be bought online from China from $6 to $20, according to the US Drug Enforcement Administration — cheaper than either heroin or fentanyl. The high provided by the animal tranquilliser lasted longer than fentanyl, he said, and could have deadly consequences because of the “sleeping stupor” it induced in users.

“It slows your heart rate down. It slows your respiratory system down and interferes with the nervous system. So, when you fall face down you can die from asphyxiation,” Taylor added.

The DEA has warned that xylazine’s rapid spread mirrors that of fentanyl several years ago. The Biden administration last month designated fentanyl adulterated with xylazine as an “emerging threat” to the US. It marks the first time Washington has targeted a chemical substance in this manner, reflecting growing concerns about the scale of the overdose crisis sweeping cities such as Philadelphia and the difficulties of helping victims.

“The overdose response to someone that is overdosing through fentanyl mixed with xylazine gets much more complicated because xylazine being a non-opioid does not respond to naloxone,” said Gupta, who visited Kensington last month.

Sold under the brand name Narcan, naloxone rapidly reverses most opioid overdoses and has become a key weapon in authorities’ efforts to stem the tide of overdose deaths after more than 1mn people lost their lives to legal opioids or fentanyl. Now, first responders are having to deploy additional techniques to revive people who are overdosing from a cocktail of fentanyl and xylazine.

“Narcan is not the only thing you have to do now,” said Melanie Beddis, programme director at Savage Sisters, a non-profit group working with addicts in Kensington. “You have to do rescue breathing and we carry oxygen tanks because xylazine affects the respiratory system and that starts to shut down,” she said.

Staff members at Savage Sisters work out of a crowded storefront near the elevated subway station in Kensington, where many drug users sleep rough. The organisation provides housing for recovering addicts, as well as food and wound care services to users in the area.

Beddis, who like most of Savage Sisters staff is a recovering addict, said many clients did not want to go to hospital even though their wounds are severe, because they were afraid of the stigma associated with drug use and of painful withdrawal symptoms. She said hospitals and rehabilitation centres desperately needed to update their protocols for care to help patients with xylazine withdrawal.

“It was the worst detox I ever had — the most painful. The xylazine definitely changed things, like I don’t think I slept more than an hour at a time for a full 30 days,” said Beddis, adding she only managed to get off drugs while in prison where they were unavailable.

Local and federal authorities are stepping up their response as the xylazine overdose crisis spreads across the country.

Gupta said the Biden administration was developing national testing, treatment and supportive care protocols, as well as strategies to identify and reduce illicit supply of xylazine. It was investing in research aimed at developing an antidote for the drug and new treatment options, he said.

Some Philadelphia hospitals have already begun providing services including wound care as well as pain relief and addiction treatment. But advocates say many healthcare centres and rehab clinics need to update their protocols to stop turning away users with wounds.

“What we need is pain medicine on top of withdrawal medications,” said Perrone. “That might look like methadone plus opioid pain relievers or Suboxone with opioid pain relievers. They need high doses because they are dependent on fentanyl.”

Some US states are tightening regulations on xylazine use and storage. Philadelphia governor Josh Shapiro said last month that he would add xylazine to Pennsylvania’s list of controlled substances, which would enable police to charge people for inappropriate use of the animal sedative.

Taylor said the new powers would help Philadelphia police take stronger action against dealers following raids.

But many addiction treatment advocates warn that criminalising xylazine misuse would only limit researchers’ ability to study and test the drug and could cause cartels to switch to even more dangerous cutting agents. They note that Washington’s half-century-long war on drugs has failed to curb transnational cartels’ ability to operate in the country.

“If we restrict access to xylazine, what’s next, you know? Drug dealers are never going to stop coming up with something to sell,” said Beddis. “Instead, we should learn more about this drug, introduce new protocols for treating people and try to get ahead of the problem.”