The RCMP is preparing to offer close protection services to both senior federal ministers and public servants in response to the rising threat of political violence, sources say.

New RCMP units are expected to offer protection to up to 10 ministers or high-level bureaucrats at a time, according to information obtained by CBC News and Radio-Canada.

These new protection units are to be assigned on a case-by-case basis to ministers or officials based on risk assessments conducted by the RCMP.

While ministers have been clamouring for more protective services for years, the government’s decision to include senior bureaucrats among the people the RCMP protects points to a growing level of alarm in official Ottawa over the threat of political violence.

“The threat environment continues to evolve,” said former clerk of the Privy Council Michael Wernick.

“We saw during the pandemic in Canada and in other countries that it is not just politicians but also officials that can be in harm’s way. It makes sense to have the ability to extend greater protection for periods of time and to rely on the assessments by security and law enforcement professionals.”

Permanent RCMP teams already protect the prime minister and the Governor General. A few cabinet ministers have received close protection services in recent years, but only on a temporary basis.

Sources tell CBC/Radio-Canada the government’s plan is to give the RCMP additional funding to double the number of protection officers it employs. The matter has gone to cabinet and is currently in front of the Treasury Board.

There are no plans to grant the same protective services to backbench MPs, opposition leaders or political aides — even though several of them also have been threatened in recent years.

The office of Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre did not respond to a question about satisfaction with current security arrangements.

Radio-Canada and CBC News granted confidentiality to sources who were not authorized to speak publicly about security issues or matters before cabinet.

A growing number of threats

Several sources pointed to the growing number of threats made in person or online against people in government in recent years.

Many threats have come from opponents of restrictions imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic. The sources said other threats against politicians or bureaucrats have been related to policy issues such as gun control or the development of natural resources — and even the controversy at Hockey Canada.

Canada’s Chief Public Health Officer Theresa Tam and other bureaucrats associated with Canada’s pandemic response have received many threats of violence.

A number of cabinet ministers also have experienced aggressive encounters in recent years, both online and in person. Last August, a video showing a man hurling profanity at Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland and calling her a “traitor” during an event in Alberta triggered a debate about threats to politicians.

WATCH: Freeland reacts to aggressive encounter in Alberta

Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland has responded to her recent harassment during a stop in Grande Prairie, Alta., over the weekend. Freeland, who was born and raised in Alberta, said she is not intimidated by the behaviour and also noted how harassment affects people other than herself.

Earlier this month, an Ontario man was sentenced to house arrest for throwing gravel at Prime Minister Justin Trudeau during an election campaign stop in 2021.

The sources said many threats against senior federal officials have never been publicized. They added that many ministers and government officials feel the RCMP does not take certain specific threats seriously enough.

The RCMP, meanwhile, says it suffers from a shortage of protection officers and has had to prioritize existing security obligations.

A three-day retreat attended by Trudeau and his cabinet in Hamilton, Ont. in January amplified the sense of vulnerability among cabinet ministers, sources said.

A small but vocal group of protesters set up outside the hotel hosting the retreat. After dinner with his ministers, Trudeau made his way back to his hotel through the crowd of protesters with the help of his protective detail. But a number of ministers lingered at the restaurant because “the police did not know how to get us out of the situation,” said a Liberal source.

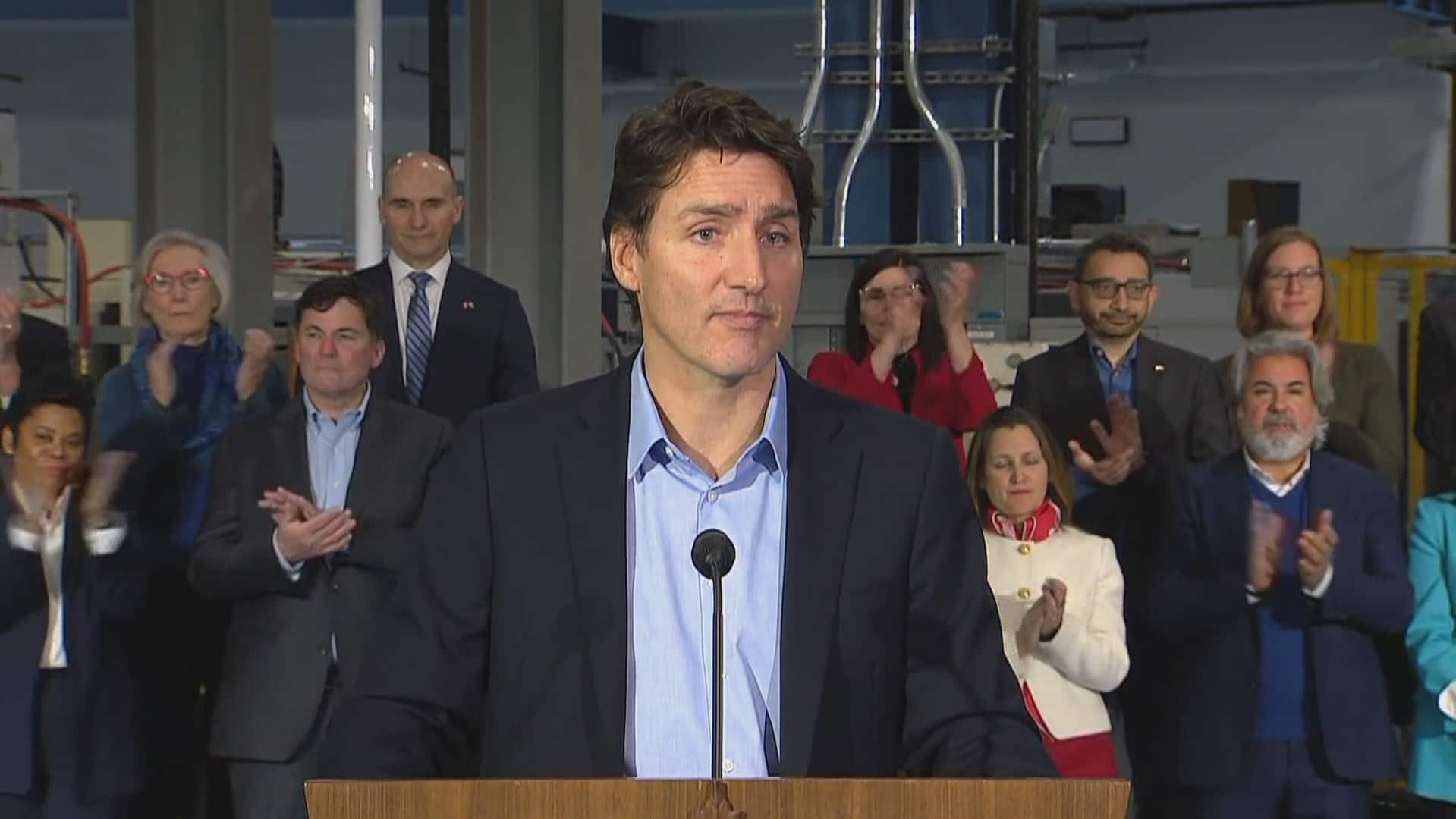

WATCH: Trudeau reacts to being swarmed by protesters

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau says a ‘handful of angry people’ do not define ‘democracy in this country.’

“What struck me was the lack of planning,” said the source.

Eventually, the group of ministers walked through the crowd of protesters with the help of the Hamilton police and at least one member of the RCMP. Some feared the situation would get out of hand, said the party source.

“They took the whole gang out of us together … It could have been catastrophic,” said the source.

The sources said the experience in Hamilton convinced cabinet of the need for expanded RCMP protective services.

Former RCMP deputy commissioner Pierre-Yves Bourduas said the threat of political violence is part of a “new normal” in Canada.

“The situation doesn’t seem to be improving and in that context, the RCMP must make sure it has the resources in place to meet the new operational challenges,” he said.

Richard Fadden, former head of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, pointed to a growing “disconnect between some parts of the population and government” as one driver for the rising number of violent threats.

“You go back 25 years, there were a lot of very unhappy people. But the disconnect … wasn’t there and I don’t think the ability to organize quickly, to bring together protests … was there,” he said.

The House of Commons also has adopted measures to better protect MPs attending events in their constituencies.

At a meeting of the Board of Internal Economy in December, the House launched a pilot project to pay security costs for events organized by MPs outside the parliamentary precinct.

The Sergeant at Arms of the House of Commons will conduct security assessments to determine whether such an event needs on-site security.

The office of government House leader Mark Holland told Radio-Canada/CBC that Parliament has introduced measures to protect individual MPs when they’re outside the parliamentary precinct, including security assessments and outreach to local police.

“For security reasons, detailed information about these programs is not shared publicly,” said the office spokesperson.