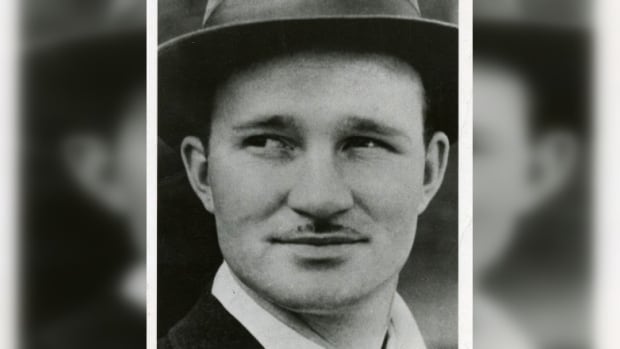

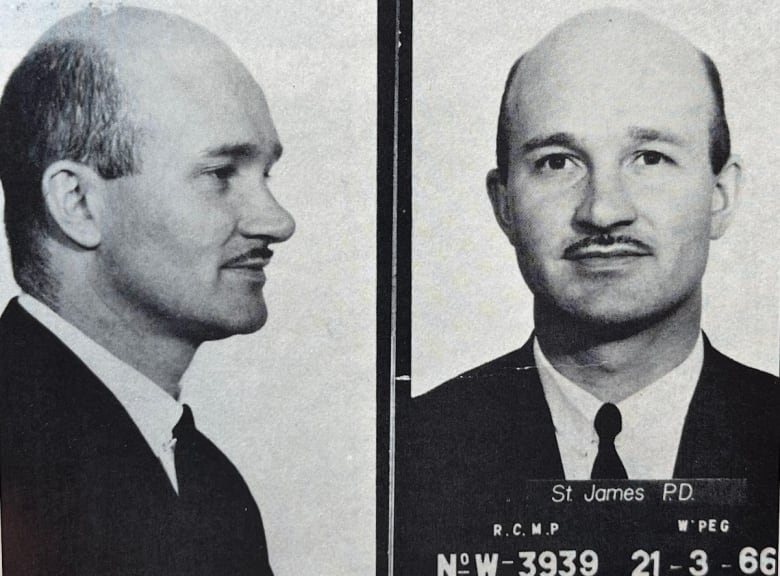

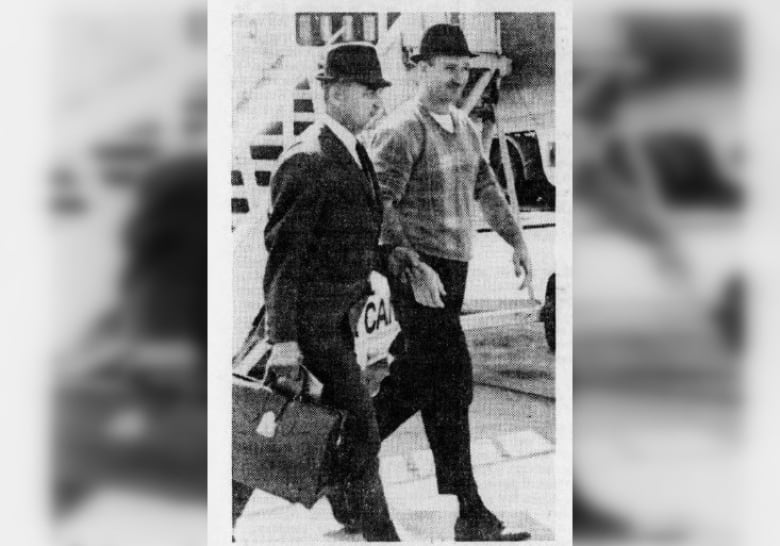

By all accounts, Winnipeg’s Ken Leishman was a dashing and delightful man, a nattily dressed charmer whose ever-present smile was capped by a tidy moustache.

With an IQ of 146, he was also blessed with a gifted mind. He pooled those qualities to rob banks, escape prisons and pull off what was then Canada’s greatest gold heist.

A plan masterminded by the cookware salesman from North Kildonan intercepted 12 gold bars worth $383,000 at the Winnipeg airport on March 1, 1966. Gold then was $35 an ounce, but today it’s $2,000, making the loot worth nearly $20 million if it were stolen now.

“It was kind of an exciting time for everybody within the city.… [It] was very unusual anywhere in the world for that time,” said Larry Dunmall, whose dad, Det.-Sgt. George Dunmall, led the police investigation.

For many in the public, Leishman was an anti-hero to cheer, said local historian Christian Cassidy, who wrote about Leishman in an online blog.

“It wasn’t a murder. People weren’t hurt. I think that was one of the things that helped make him a bit of a folk hero,” Cassidy said in an interview.

“He was sticking it to the man. He wasn’t holding up little old ladies or beating people up and stealing their money.”

George Dunmall was on the other side of the case and even he tipped his hat.

“It was just a masterfully planned and executed operation,” Larry said in an interview.

“When some criminal activities are done properly, without violence, there’s a space to say, well that was quite the plan. And my dad certainly did appreciate a good plan.”

It remained unsurpassed until last week.

Gold and other valuable items, worth some $20 million, were taken from a holding facility at Toronto’s Pearson International Airport on April 17. No arrests have been made.

The theft resembles Leishman’s template, but he’s not a suspect — he died in December 1979 in a plane crash in the northern Ontario wilderness.

It was a dark ending that book-ended a similar start. Born in 1931, Leishman was shuffled through foster homes, then taken from an abusive one by Children’s Aid.

At 18, he married Elva Shields and began a family that grew to seven kids, and worked for a mechanical company that serviced buildings.

He stole from some businesses where he did repair work, returning after hours to break in.

Leishman stole everything from a radio to a fridge, stove and entire bedroom suite, Cassidy said.

He moved the large items by posing as an employee of the business and calling transport companies to pick up and deliver them. A suspicious dispatcher one night called police and Leishman served three months in jail.

But it didn’t deter him. Rather, his crimes took off.

He learned to fly small planes and visited rural communities for machinery repair. He bought a used two-seater and the family appeared to be doing well, with a nice house in River Heights, new car, good wardrobe and plane.

The facade, though, was embellished by crime. In December 1957, Leishman went to Toronto and robbed a bank of $10,000, exuding charm the entire time, which earned him the Gentleman Bandit nickname.

A return visit in March 1958 was less successful. He tripped and was held until police arrived. He got 12 years for the two robberies and a new nickname: The Flying Bandit.

Leishman, described as a model prisoner, was paroled after 3½ years. A new job selling cookware and a new home in North Kildonan appeared to put him on a new path.

But Leishman’s old ways clung like an obsession.

He discovered a small airline regularly flew into Winnipeg from the gold mines in Red Lake, Ont. It carried gold bricks that were passed to an Air Canada crew, then sent on a flight to the Royal Canadian Mint in Ottawa.

Leishman rounded up four accomplices and drew up a plan. They secured coveralls and parkas similar to Air Canada ones and stenciled on the airline logo.

When a plane arrived from the mines on the evening of March 1, 1966, Leishman’s team stole an Air Canada cargo van and drove onto the tarmac to meet it. They presented a phony waybill, loaded up the gold and drove off.

They dumped the van about a kilometre away and moved the bricks to another vehicle. They planned to stash them at a farmyard, but an impending blizzard thwarted that, so they unloaded them at the home of Harry Backlin, a city lawyer and Leishman’s main heist partner.

The blizzard also complicated the investigation, erasing tracks and other evidence, Dunmall said.

In a 1978 Winnipeg Tribune story, Leishman said he wanted to store the gold for a few years but others wanted to be paid right away. So he and Backlin decided to sell it overseas.

They cut a chunk with a hacksaw and Leishman boarded a train to Vancouver on March 7, where he was to catch a flight to Hong Kong.

But RCMP were waiting at the airport.

During Leishman’s two-day train trip, investigators in Winnipeg had found the abandoned cargo van and a fingerprint. They also located his car at the airport and in it a notepad with indentations that, with some light shading, revealed Backlin’s name.

Det.-Sgt. Dunmall paid a visit to Backlin’s law practice, casually pacing the office as they spoke, his son said.

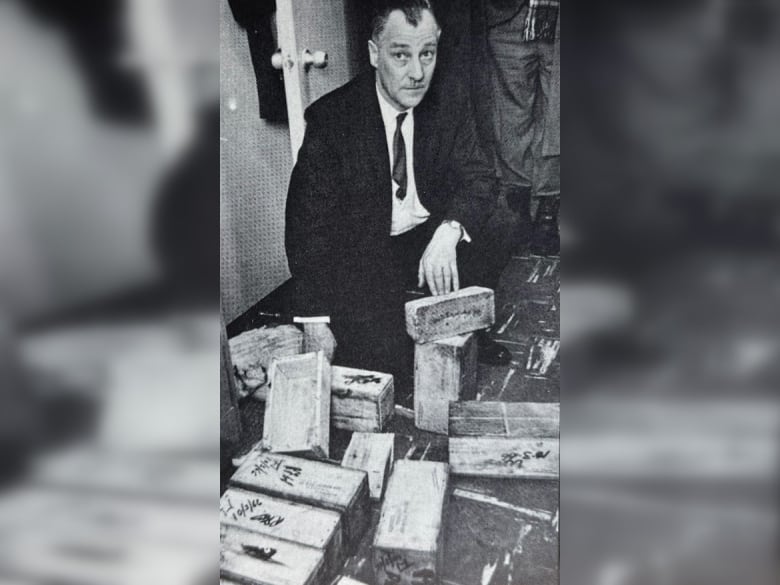

“He noticed a briefcase sitting beside Mr. Backlin’s desk and he kind of just pushed it with his foot and immediately noticed it was extremely heavy,” Larry Dunmall said.

“He opened it and inside was a large section of a gold bar. And at that moment the world changed.

The other gold was recovered from Backlin’s house, some in his basement deep freeze, under slabs of moose meat, some outside, under snow.

In the 1978 Tribune interview, Leishman said he ditched his gold nugget before RCMP took him into custody. He never understood why Backlin kept the rest of it in the briefcase.

“The plan was that he would return that piece to the freezer. It was stupid,” he said.

Leishman’s crew were locked up, but it wasn’t his last adventure. He led two jailbreaks and was eventually given 15 years for his crimes.

Paroled after serving eight, he moved the family to Red Lake for a fresh start.

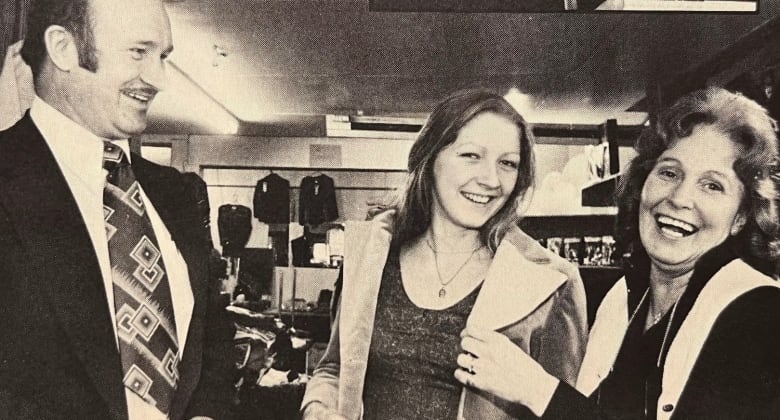

He got a job as a bush pilot and Elva opened a gift shop. They were embraced there — Leishman even elected president of the Chamber of Commerce. He also began airlifting people from remote communities to hospital in Thunder Bay.

That 1978 fateful flight carried a patient and medical assistant. The wreckage, and their bodies, weren’t discovered until spring.

Leishman’s body, though, was nowhere — just a wallet and scraps of clothing. An inquest later concluded it was likely taken by wolves and he was declared legally dead at age 48.

As for the gold he ditched in B.C. 12 years earlier? It was never found.