Since the pandemic began, Lyft employees have been able to work remotely, logging into videoconferences from their homes and dispersing across the country like many other tech workers. Last year, the company made that policy official, telling staff that work would be “fully flexible” and subleasing floors of its offices in San Francisco and elsewhere.

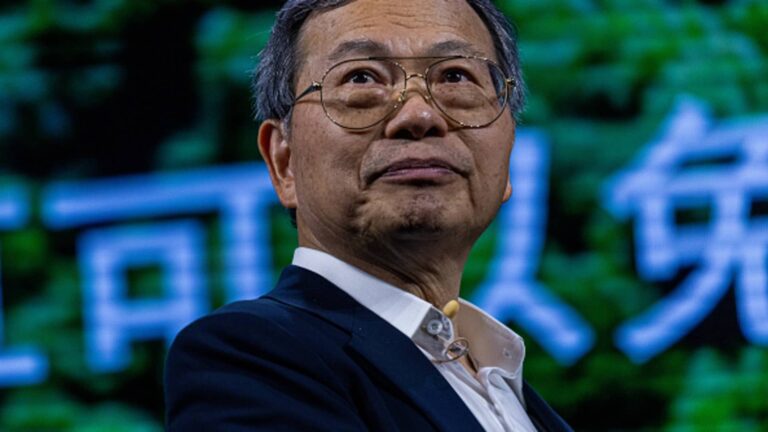

No longer. On Friday, David Risher, the company’s new chief executive, told employees in an all-hands meeting that they would be required to come back into the office at least three days a week, starting this fall. It was one of the first major changes he’s made at the struggling ride-hailing company since starting earlier this month, and it came just a day after he laid off 26 percent of Lyft’s work force.

“Things just move faster when you’re face-to-face,” Mr. Risher said in an interview. Remote work in the tech industry, he said, had come at a cost, leading to isolation and eroding culture. “There’s a real feeling of satisfaction that comes from working together at a white board on a problem.”

The decision, combined with the layoffs and other changes, signals the beginning of a new chapter at Lyft. It could also be an indication that some tech companies — particularly firms that are struggling — may be changing their minds on flexibility about where employees work. Nudges toward working in the office could soon turn into demands.

After lagging behind its rival, Uber, in the race to emerge from the pandemic doldrums, Lyft posted worrisome financial results in February. Its co-founders, Logan Green and John Zimmer, said the following month that they would step down.

Mr. Risher, a veteran of Microsoft and Amazon who also served on Lyft’s board of directors, has laid out a plan to streamline the business, cut costs and focus on improving the quality and lowering the price of Lyft’s core product: offering rides to consumers.

Lyft employees have complained that divisions outside the core ride-hailing business, like units that offer its gig drivers cars to rent and that rented bikes and scooters to consumers, seemed to be disproportionately affected by the layoffs. Mr. Risher said the cuts were across the board.

He said the cost savings from the layoffs would go toward lower prices for riders and higher earnings for drivers.

The next phase of his plan, he said, was to remind riders that Lyft is a viable alternative to Uber. In the summer, Mr. Risher said he would gradually introduce products to increase interest in the platform. That might include partnering with companies to offer Lyft rides to their employees who are commuting to offices, he said.

The next steps for the company will be difficult. Many Lyft employees have gotten used to working from home, and some were already bristling at the possibility of returning to the office. Lyft continues to trail Uber, which has a global ride-hailing business and also offers food delivery.

Lyft’s stock price is trading at $10 a share, down from $78 at its peak, and some have speculated that it could be an acquisition target. The company will report financial results for its most recent quarter next week and expects $975 million in revenue, lower than the $1.1 billion investors had hoped for earlier this year. It is not yet profitable.

Mr. Risher announced a handful of other changes on Thursday. He ended products focused on car rentals, as well as shared rides and luxury rides, and he promoted Kristin Sverchek, the head of business affairs, to president.

Lyft also planned to tell employees that it would reduce their stock grants this year, according to a person familiar with the decision.

The return to office plan, Mr. Risher said, would require workers to come in Mondays, Wednesdays and Thursdays, with Tuesdays recommended, beginning after Labor Day. People will be allowed to work remotely for one month each year, and those living far from offices would not be required to come in.

Mr. Risher said he saw the moment as an opportunity to have a “cultural reset, particularly around decision-making.”

He said Lyft was successful with its early ride-hailing business, but that Mr. Green’s and Mr. Zimmer’s idea to build a transportation network, with products focused on scooters, bikes, parking and rental cars, “didn’t really resonate with people.”

“So now, my focus is saying, ‘Gosh, in ride share alone, there’s an enormous amount of innovation left. People desperately want to get out and live their lives, and we can help them,’” Mr. Risher said. “And then maybe, over time, we can build some things back on top of that.”