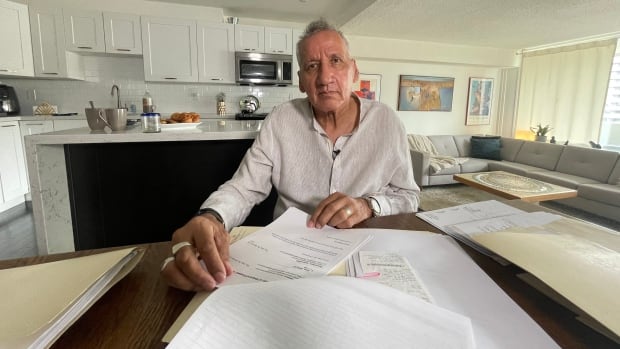

An Ojibway man in Toronto is contemplating his next steps in a five-year battle with Indigenous Services Canada over Indian status after learning the Canadian Human Rights Commission (CHRC) might not deal with his complaint against the department.

Alan Lawrence, 75, spent four decades as a videographer, and said he was sometimes hired because he was Indigenous so producers could obtain specific funding. He applied for Indian Status five years ago.

“I feel that I’ve lost five years of my intent, purpose of finding my identity.”

“My real identity,” said Lawrence.

His mother registered for Indian status with Fort William First Nation in northwestern Ontario after Bill C-31 was passed in 1985, he said.

Lawrence sent his application to ISC in April 2018 and received a rejection the following year under what’s known as the second generation cut-off. ISC questioned the eligibility of his maternal grandmother, leaving his mother entitled to status under section 6(2) – meaning any child she has with someone who is non-status will not be entitled to be registered, according to the Indian Act.

He filed a protest and sent in new family history material and his DNA analysis from an online website. Lawrence was sent a letter indicating that there could be a decision on his protest within 90 days. ISC has yet to issue a decision on his protest.

“I’m talking dozens, scores of auto replies and countless hours on the phone on hold, only [to] be told that, yeah, somebody will get back to you within a two or three weeks,” he said.

He filed a complaint with the CHRC in May 2021 and last month received a report for a decision, a document prepared by public servants to assist commissioners in deciding independently, recommending it not be dealt with.

The report concluded that the complaint didn’t relate to a discriminatory practice within the meaning of the Canadian Human Rights Act because it disputes a decision made based on a predetermined formula — the entitlement provisions of the Indian Act — and the complaint can’t succeed.

However, commissioners regularly make decisions that don’t agree with the report recommendations and Lawrence’s complaint has been sent to them for a final decision.

Hundreds of protests

Lawrence’s story is one example out of hundreds of protests over Indian status decisions. There are currently 383 at different stages of the process, according to ISC.

A protest is a written request to the Indian Registrar over a decision about adding or removing someone from the register or First Nations band list that is maintained by the department.

According to ISC, since July 2021:

- 281 protests were presented to the Indian Registrar.

- 108 final decisions were made: 3 were upheld, 103 were found invalid, 2 were not upheld.

In a statement to CBC News, Indigenous Services Minister Patty Hajdu said she cannot comment on individual cases but said the federal government is committed to addressing inequities in the registration of the Indian Act.

“We will be pursuing consultations on further areas of concern, like the second generation cut-off. We’ll continue working in partnership with Indigenous Peoples to address all remaining inequities.” said Hajdu.

Family support

Once a final decision is made on a protest, it can be appealed in court.

Lawrence has considered court action but cannot take any steps in that direction until a decision is rendered on the protest.

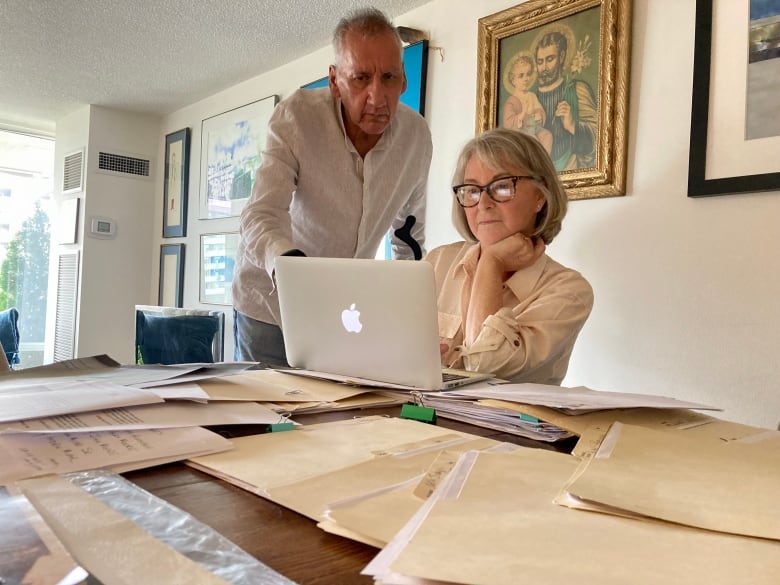

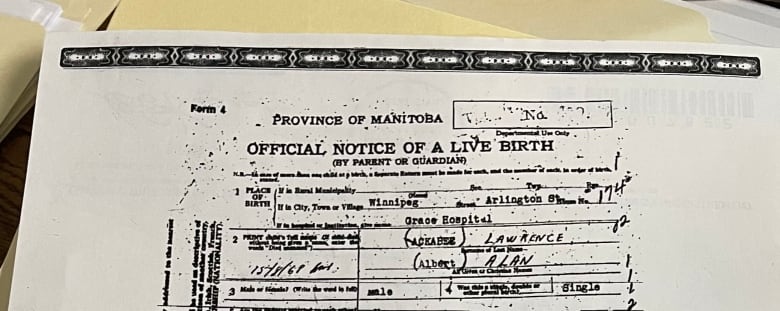

His family has gone through the application process with him, his wife taking on the brunt of the research and document gathering, starting with his birth certificate.

“He was mislabelled, miscast, misidentified right from the get-go when he was born,” said Patricia Onysko during an interview with CBC News last June.

“It has his mom as a French half-breed, which she wasn’t, and we’ve got the DNA evidence that shows there’s not a smidgen of French in her anywhere,” she said.

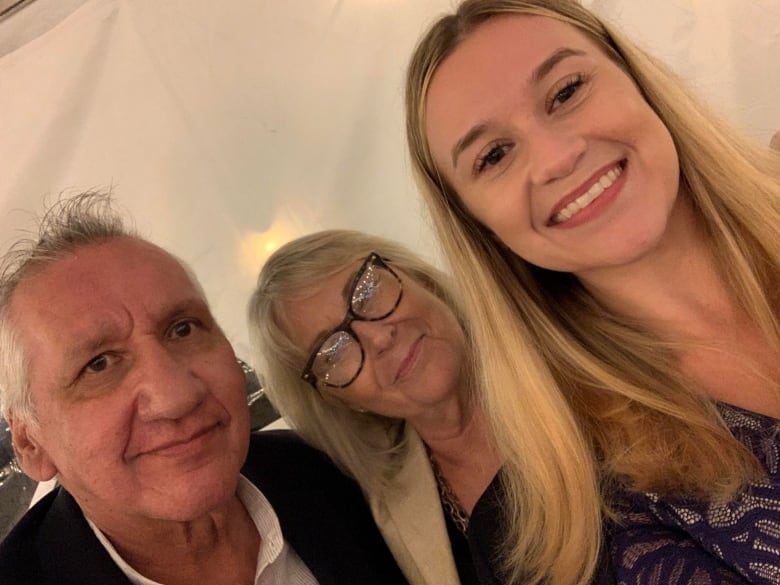

In New York City, his daughter Toni Lawrence works an administrative job in a corporate environment and said she knows the difficulties in bureaucracy but it still takes an emotional toll on her.

“It’s hard to see my dad have to go through this,” she said.

“I feel sad because I realized that our family has the time and the resources and the wherewithal to keep pushing this. And I know that’s not the case for so many people and so many families.”

Lawrence plans to take further steps with the CHRC and continues to wait for a decision from ISC.

In the meantime, he continues to live his day-to-day life as a First Nations person. He has been singing and drumming with the Native Canadian Centre of Toronto and said he would love to hit the powwow circuit again soon to take photographs and video.

“I want to be recognized as an Indian, as an Ojibway person in Canada,” he said.

“So I’m looking for accountability. And justice. And hopefully a little plastic card.”