It is 50 years since I was last driven up this long track towards the Tuscan farmhouse where artists Maro Gorky and Matthew Spender have lived and worked since 1968. Pollarded limes interspersed with the occasional sculpted figure lead the eye to the old building, ringed by cypresses, where we are met by a peacock, resplendent in his uniform of blue and green.

Matthew – sculptor, painter, author – appears from the side of the house: tall, white-haired, stretching out his hand in welcome. It is Maro I have come to interview, in view of her forthcoming retrospective show at London’s Long & Ryle, which marks her 80th birthday next week, but I am aware that the couple form a strong creative partnership. Spender, 78, has written eloquently about his wife’s work, and throughout the day they engage in good-humoured banter. Both can be sharp and observant, with Maro often disarmingly direct.

“The remarkable thing about us,” she says, as we sit in the kitchen, originally the stables, “is that we manage to live in the country, without having love affairs with anyone else, and we hardly see anybody, and we’ve been together for 62 years! A nightly bottle of wine has helped…”

The couple’s credentials as bohemian aristocracy are indisputable. She is the daughter of Armenian-American artist Arshile Gorky, he is the son of acclaimed poet and critic Sir Stephen Spender, and – despite that assertion that they “hardly see anybody” – through this house have passed writers, artists, actors and filmmakers of some renown. Bernardo Bertolucci used it as inspiration for his film Stealing Beauty. Their elder daughter Saskia is a ceramicist; younger daughter Cosima a filmmaker and producer. Satirist Barry Humphries is married to Matthew’s sister. Mine and Maro’s mothers knew each other too; mine the Florentine art historian Luisa Vertova, hers a “professional beauty” (Maro’s words). I share my memories of visiting the house at some time in the ’70s. I remember a bold painting of Matthew’s based on the Renaissance artist Paolo Uccello’s The Battle of San Romano. “Oh yes – that’s rolled up somewhere…”

The stability of this home is all the more heartening if you consider the insecurity of Maro’s childhood. In 1948, when she was five years old, her father died by suicide. Maro was sent with her younger sister Natasha to what she describes as an “orphanage in Switzerland” for six months. The children were then parcelled around a sequence of different family homes and schools in Europe and America. She ended up at the French Lycée in London (which she enjoyed), followed by the Slade School of Fine Art, graduating in 1965. Her tutors there were Jeffery Camp, Frank Auerbach (“good teachers, both”) and Thomas Monnington, later president of the Royal Academy, who she feels was more interested in Matthew’s work. (At one point he suggested she might “do like my wife did – she’s a nurse, she supports me”, says Maro.)

Maro always wanted to paint. She remembers cutting out coloured paper and playing with crayons from a very early age. “My father said I was a born artist. He didn’t want me to go to school at all, he wanted me to paint, and when I was three and a half I had a little easel, and little Winsor & Newton paints. I was allowed to paint on the back of his canvases, but I was obviously a rather egocentric child and would try to start painting on the front, and then he’d hurl me out of the studio.” The surrealists Roberto Matta and André Breton, both in Arshile Gorky’s circle, taught her another approach: to “just put colours on the canvas without an idea – what you want and like, and then see what you see”.

The farmhouse, half an hour north of Siena, was a wreck when they bought it 55 years ago, with animals living below. It was a simpler but poorer time. Oxen were still used to work the land, olive groves outnumbered vineyards, there were hardly any cars. Abandoned farmhouses dotted the countryside and land was cheap but neglected. “Apparently there had been huge pear trees here that produced marvellous fruit but they’d all been cut down,” says Maro wistfully. “It was desolate. Since then we’ve planted about 4,000 trees.” There was a sense of forging a life away from the city, of connecting with the earth. “I spent a lot of time chopping vegetables,” says Maro. There was hardly any electricity, no plastic, and clothes were washed in the fountain at the bottom of the hill.

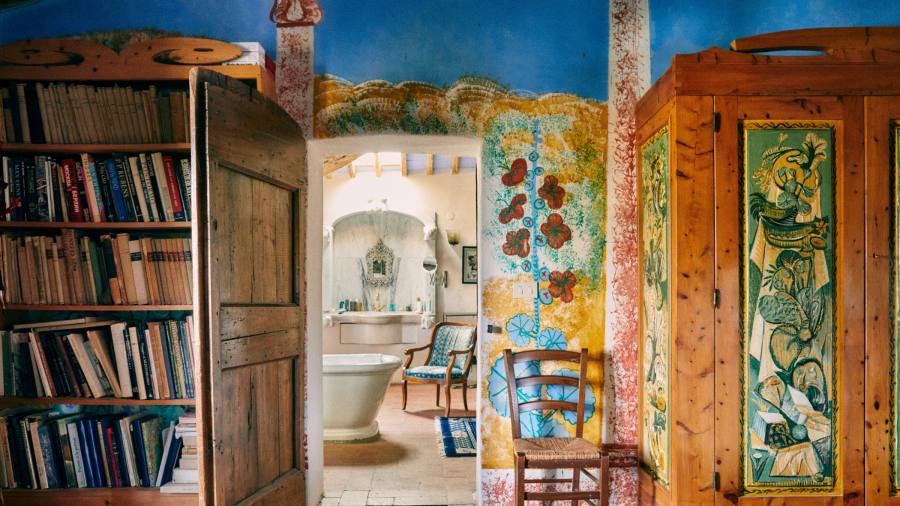

Part of that way of life included – and still includes – making and recycling as much as possible. The kitchen sink was salvaged from the mortuary of Careggi hospital in Florence; the wooden doors beneath were constructed by Matthew, as was much of the furniture in the house. Food is served on beautiful glazed terracotta plates created by Maro, in a style she describes as “churchy, oriental, Armenian”. Behind the range is a tiled wall she designed in 1986. Within its compositional lines every tile has its own motif, so each unit functions separately as well as being part of the whole.

Colour and pattern infuse the other rooms, decorating the walls and the furniture. “Not so much decorating,” corrects Matthew, turning to Maro, “they are extensions of your painting, except…” “…they are decorative,” says Maro, and they both laugh.

Painted columns meet real beams, more evocative of the houses and villas of Pompeii than Bloomsbury Charleston. In the rooms, objects mix in an Aladdin’s cave of international treasures: an Indian bed, English patterned bed covers, Greek cushions, Egyptian alabaster vases, an African ostrich egg. And always an eye for the idiosyncratic. The lavatory in the palatial bathroom is, explains Maro, “a copy of the papal throne belonging to Boniface VIII when he was imprisoned in Anagni…”

And from each window appears the unspoilt Tuscan countryside. Matthew points out that Maro has painted the view from every room, including the one from the window above the bidet. Like the undulating land, always slightly off-kilter, there is often a tilt in the artist’s work, an element of vertigo. Anchoring her paintings are the geometric shapes of the trees and hills, the stone walls, the poles that support the vines in the fields – forms that have become more abstract as Maro has grown older. For years she sketched and painted in front of this terrain; now she generally waits. “If the images I want to record are strong enough for me to remember afterwards then I know it’s worthy of being done.”

In her portraits are references to Old Masters, but the subjects are subverted, so that Manet’s Olympia becomes a naked black man, with Olympia’s black slave turned into a little privileged white boy, while Saskia on the Rocking Horse (1981), a nod to Velázquez, depicts Maro’s elder daughter dressed in a flamenco costume pictured against the local landscape. A full colour palette is on display: reds, greens, yellows, browns, pinks and blues.

Maro talks about the stimulating sensation that occurs when she looks at colour – “like an itch” in the palm of both her hands. Her use of powder paint on paper becomes an emotional reaction to the shade. “I have noticed that older painters seem to simplify and have brighter colours because their eyes can’t see so well. They put more colour in.” She says her forthcoming retrospective is an honour – she turns 80 on 5 April – although “I am the same person I was when I was five”. She adds, “I have now what I wanted even then: paints, and a decisive path through my emotional landscape.” Walking around, we stop at her most recent, as yet untitled painting, inspired by a trip to Armenia. “My father’s birthplace,” she says, and agrees that this title should stick.

Back in the kitchen it is teatime and we tuck into a delicious apple pie made by Matthew. I imagine the table on which we eat as a meeting place for discussions with friends and family about life, art, politics, relationships. Yet, despite their connections, the couple remain refreshingly unimpressed by the famous “names”. Maro is sharp about a miserable stay, many years ago, with Duncan Grant at Charleston: “It was so cold, so uncomfortable, no hot water, no heating in the bedroom, a dreadful weekend.” Mention of Sir Harold Acton, Florence’s most famous British aesthete, gets the aside “such a terrible bore”. Another famed expat, Violet Trefusis – lover of my grandmother Vita Sackville-West – is dubbed “a colourful old parrot”.

One last memory of mine is the swimming pool being on a lower level of the garden. That summer day in the ’70s, Saskia and Cosima invited me to swim. The adults were elsewhere, but as an awkward teenager I was too embarrassed to remove my clothes to swim naked with these much younger girls. It is too late to wander down to the pool now, though, so we remain talking awhile before I get back into the car. As the light fades, we notice that the peacock is roosting in a tree, a silhouette set against the greys and purples of an evening sky, all his colours gone. On the way back to Florence I think about how Maro Gorky, while staying true to her art, has managed so successfully to create a family and a home; those things lacking for her as a child. To make her mark, and to put it right.

Maro Gorky, A Life Painting is at Long & Ryle, 4 John Islip St, London SW1, from 19 April to 12 May; longandryle.com