Craig Coben is a former global head of equity capital markets at Bank of America and now a managing director at Seda Experts, an expert witness firm specialising in financial services.

Spring may have arrived, but investment banking is still in the winter of its discontent.

After a dismal 2022, bankers banked on a recovery in dealmaking in 2023. Although stock markets have performed well in 2023, boardroom caution, higher interest rates and recent ructions in the banking sector have dried up deal flow. Here’s Ivan Levingston at mainFT today:

Global dealmaking suffered its weakest start to the year in a decade, as a darkening economic outlook depressed activity and a transatlantic banking crisis put the brakes on risk taking in the first quarter.

The value of mergers and acquisitions dropped 45 per cent year-on-year to $550.5bn between January and March, the largest decline in the first quarter since 2001, according to data from Refinitiv.

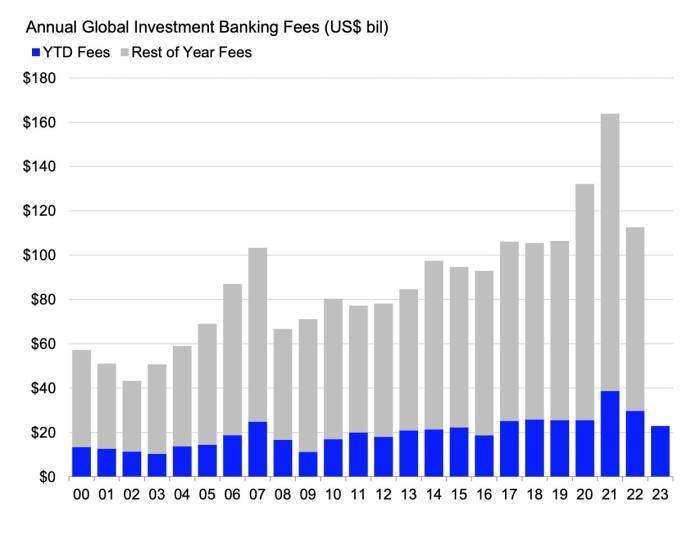

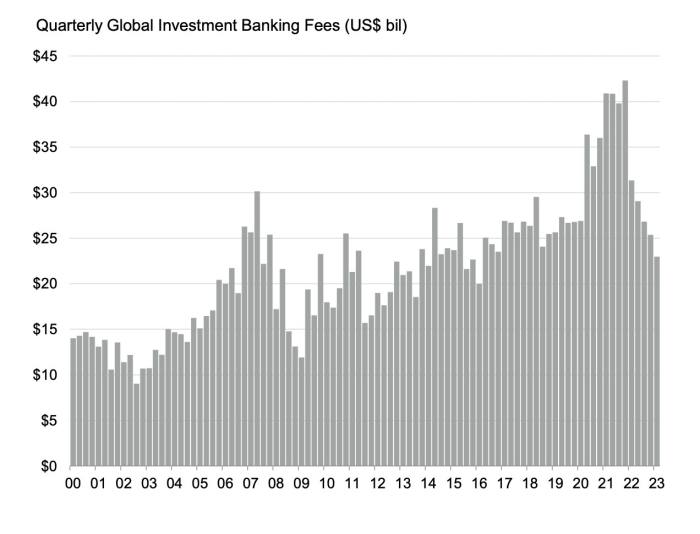

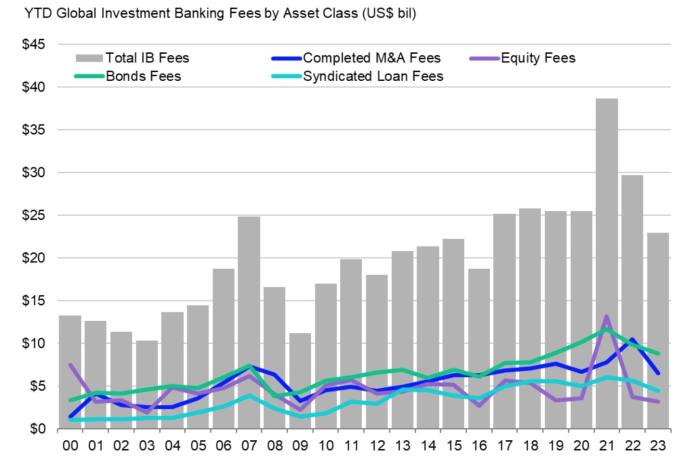

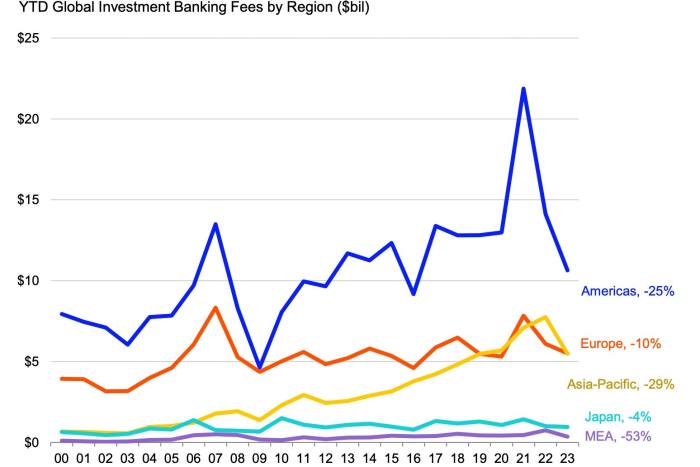

It wasn’t just M&A. There were no bright spots. Every part of investment banking suffered a drought in the first three months of 2023, and every single region saw a decline. Global investment bank fees fell 23 per cent year-on-year — the fifth consecutive quarter of declines — to $22.9bn, according to Refinitiv.

One can’t draw too many conclusions from a slow first quarter. There is a lot of seasonality to dealmaking: Capital markets offerings often launch off audited year-end financials, meaning that mid- or late-spring can be quite busy. And dealmaking is lumpy, with juxtaposed periods of feast and famine.

Still, the numbers are sobering, and they don’t even tell the whole story. Transaction volumes were higher in certain products, such as equity underwriting in the US and Europe, but deals were lower-margin for the investment banks. More block trades and fewer IPOs, for example, make for a worse product mix.

A sluggish-to-comatose IPO market was predictable, but it’s still shocking to see a 61 per cent year-on-year fall in global IPO proceeds in the first quarter 2023. There’s not much margin for profit — or error — when buying a €2.2bn block of BNP Paribas shares from the Belgian government at a 1.8 per cent discount.

Investment banks now must decide about staffing levels. Projects in advisory and capital markets businesses are labour-intensive and bespoke, and can’t be easily automated. Banks need both “show horses and work horses” — ie senior client-facing bankers to pitch the business, and junior and mid-level bankers to prepare materials and execute the deals. Moreover, it takes time to recruit (and train) both senior and junior personnel.

I lived through severe downturns, and they are as tough to work through as they are to manage. Morale plummets even faster than compensation. While the media today invokes the 2008 financial crisis and the phoenix-like recovery of capital markets in 2009, for me the aftermath of the TMT bubble bursting in 2001-03 stands out.

During the early 2000s investment banks implemented so many successive RIFs (reductions in force) that — as in Clint Eastwood’s famous oration in Dirty Harry — we “kinda lost track” if there were six rounds or “only five”. Huge teams were culled, and hitherto productive bankers were shown the door. Several close friends at work were let go.

Meanwhile, we had to keep ourselves active. We told each other that in slow times clients wanted to hear what was happening in the markets, even if they had no plans for a deal. We ramped up client calling efforts. Any missed mandate (known as “Deal Done Away” or just DDA) was especially painful given the paucity of transactions. Overall, we were a lot busier than we were productive.

By the time markets improved in 2004, banks had pared headcount so much that they were understaffed and forced to pay up to recruit laterally from other banks.

So what should banks do with headcount in the current slowdown? Loose Covid-era fiscal and monetary policy translated into a massive upswing of deal activity, and banks scrambled to recruit. Headcount grew by about a third. But now they are left with too many bankers working on too little business. Revenue per employee has plunged.

Yet no bank wants to be caught short-handed if central banks reverse course and dealmaking returns to normal levels.

Investment banks are taking different approaches. Several have reportedly carried out broad-based redundancies to reduce costs in expectation of a prolonged slump. Others have so far avoided mass job cuts, opting for natural attrition to gradually bring down employee numbers. Rumours abound of further RIFs as early as next month.

Some banks have targeted expensive senior talent and protected junior employees. Others are reducing analyst and associate headcount, because so many had been hired and performance reviews to weed out weaker juniors were de facto suspended during the Covid period for compassionate reasons.

At this point nobody knows which approach makes the most sense. Ideally, a bank would keep its headcount largely untouched and use variable pay to cap costs. That is starting to bite. From the FT yesterday:

Wall Street bonuses fell last year by the most since the financial crisis, dropping 26 per cent to an average of $176,000 amid higher rates and a decline in dealmaking, according to a report from the New York state comptroller.

The drop in payouts — the biggest since 2008, when year-end incentive payments fell 43 per cent — came as a rocky stock market led to a dearth of deals last year. The comptroller’s office blamed the drop in bonuses on a rise in interest rates, recession fears and the war in Ukraine.

But there are limits to that approach. For one thing, salaries have increased substantially post-financial crisis, and the practice of paying “role-based allowances” to sidestep the EU bonus cap has ratcheted up fixed costs even more in Europe.

So cutting variable compensation will save less now than in 2001-03.

For another, lower compensation demoralises strong performers and dulls incentives. It takes a strong culture of organisational trust to convince bankers to accept pay restraint now in exchange for keeping the franchise intact. The danger is a kind of adverse selection where the biggest contributors leave the bank and the hangers-on . . . hang on.

These tensions will play themselves out in coming months, as banks mediate between the need to reduce costs dramatically with a desire to protect franchises they have painstakingly built. The pressures will become more acute, and the choices more unpalatable, the longer that activity stays in the doldrums.

Banks need to determine if the slowdown is prolonged as in 2001-03, or short and sharp as in 2008, or a new phenomenon forcing a reset of business models and staffing. Getting it wrong will be painful.