A Canadian biotech company has developed new test strips to detect the dangerous animal tranquillizer xylazine in the highly toxic street drug supply — but while the strips are already shipping across the U.S., Canada hasn’t yet approved the potentially lifesaving tool.

Xylazine, also known as “tranq,” “tranq dope” or “zombie drug,” is a severely potent veterinary tranquillizer typically used as a sedative in large farm animals such as horses that is being cut with opioids like fentanyl to prolong their effects.

The sedative is not approved for use in humans in Canada and its long-term effects on human health are unknown, but it can cause hours-long blackouts, and studies have shown those who inject drugs that contain xylazine may develop horrific, painful wounds or lesions that can lead to amputation if left untreated.

Health officials have said the sedative can also drastically slow breathing, lower blood pressure and drop heart rate, while greatly increasing the risk of fatal overdoses when mixed with opioids like fentanyl.

To make a bad situation worse, one of the best overdose prevention tools available — the life-saving overdose-reversal medication naloxone — is rendered completely ineffective against xylazine because it’s not an opioid, meaning attempts to revive people can be futile. Harm reduction advocates and substance use experts warn that this is greatly increasing the risk for fatal overdoses.

A dangerous animal tranquillizer called xylazine is increasingly finding its way into the illegal drug supply, Health Canada data shows. The drug can cause serious side effects and is resistant to naloxone, the fast-acting medication that can reverse opioid overdoses.

Xylazine rapidly spreading in Canada, U.S.

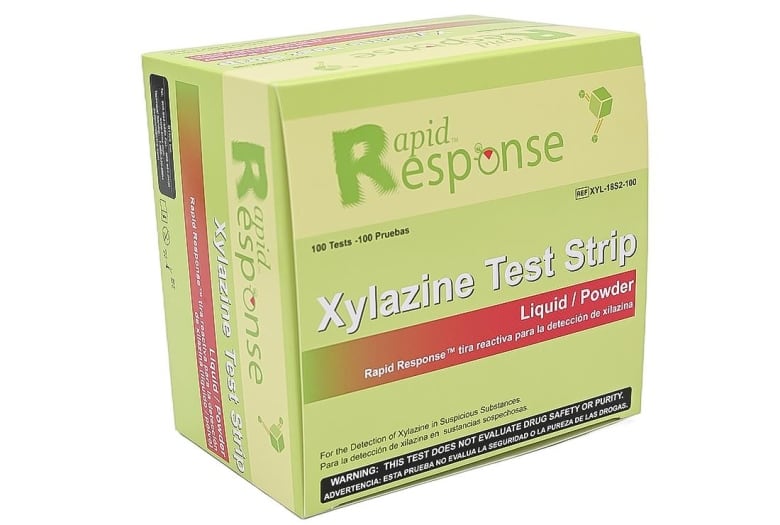

The test strips developed by Canadian biotech company BTNX Inc., work similarly to ones it makes to detect fentanyl. They can allow users, harm reduction workers and public health units to easily test street drugs for xylazine, which is increasingly showing up in the supply.

A recent report from Health Canada shows the rapid spread of xylazine across the country during the past few years, with a growing number of street drug samples seized by law enforcement agencies testing positive for the tranquillizer — overwhelmingly in Ontario.

In 2018, there were just five samples of xylazine analyzed by Health Canada’s Drug Analysis Service, which tests tens of thousands of drugs apprehended by the Canada Border Services Agency, the Correctional Service of Canada and police forces each year.

By 2019, that number grew to 205. Last year alone there were 1,350.

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration released a public safety alert in November warning that its labs found xylazine in seven per cent of fentanyl pills and 23 per cent of fentanyl powder seized by law enforcement.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has moved to restrict imports of pharmaceutical ingredients used to manufacture xylazine, while U.S. Congress has moved to add the tranquillizer to its list of controlled substances to help law enforcement crack down on it.

Test strips not yet approved in Canada

Health Canada said in a statement to CBC News that it is currently working with law enforcement and other stakeholders to determine what further actions can be taken to address the illegal importation of xylazine into Canada.

“Xylazine, an authorized prescription veterinary drug that has been approved for use in animals but not humans, is subject to the Food and Drugs Act and its regulations,” a spokesperson said. “However, it is currently not controlled under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act.”

Health Canada also confirmed the xylazine test strips are not yet licensed for sale in Canada, but did receive a medical device licence application from BTNX on March 17 and said the application is currently in process. BTNX is also one of the largest suppliers of COVID-19 rapid tests in Canada.

Toronto Public Health said in a statement to CBC News that the strips are not yet being used for drug checking, while a Vancouver Coastal Health spokesperson said they are currently considering whether the strips would be a useful addition.

BTNX CEO Iqbal Sunderani said that while the company is still awaiting Health Canada approval for the test strips, they were evaluated in a lab study from the Philadelphia Department of Public Health (PDPH) and found to be effective at detecting xylazine in drug samples.

“Until we get Health Canada approval, the tests cannot be used here, but we expect to see the approval very quickly,” Sunderani said. “We’ve sent out close to 100,000 tests, predominantly in the U.S. Now we’re ramping it up.”

‘Very promising’ at detecting xylazine

The PDPH study found that the xylazine test strips were sensitive enough to be used in harm reduction settings, but they did produce false positives when a cutting agent called lidocaine that is typically found in cocaine was also present.

“We found that the results were very promising, all the samples that had xylazine — the strips were positive,” said Alex Krotulski, a forensic toxicologist and associate director of the Center for Forensic Science Research & Education who was lead researcher on the report.

“That means we never had a false negative result where xylazine was in the sample.”

Philadelphia has been the epicentre of the damages of xylazine with more than 90 per of lab-tested fentanyl samples testing positive for xylazine, according to the latest drug testing data from PDPH.

“Test strips are going to be really important from a public health perspective, because it may be the early warning that they need when those strips start turning positive,” said Krotulski. “It’s going to be a tool for public health in the field.”

He said the issue with lidocaine may not significantly affect the use of the strips by harm reduction workers and on the street, because they would be less frequently tested on cocaine samples where xylazine is much less likely to appear.

Health Canada recently said in a report that xylazine only appeared in 3.6 per cent of cocaine samples seized by law enforcement, compared with 92.5 per cent for fentanyl.

“For cocaine it’s not very good,” Sunderani said of the tests. “But with fentanyl it’s effective.”

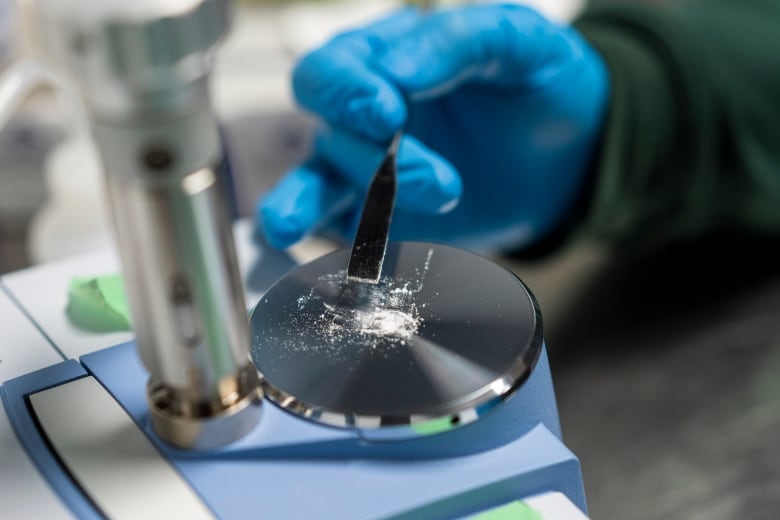

How the tests work

He said the tests typically sell for about $2 each, or $200 for a box of 100, which is significantly higher than the cost of the fentanyl test strips the company also makes.

The strips are placed into a mixture of water and a sample of the drug to be tested. If the test is positive, a single red line will appear indicating the presence of xylazine, Sunderani said. The company notes on its website that the test strips cannot evaluate the safety or potency of the drug.

“Any information is good information, we need to give people options. So I think it would be excellent if these test strips worked,” said Karen McDonald, the lead for Toronto’s Drug Checking Service.

“We also have to be realistic about the fact that it’s xylazine now, but it’s going to be something else very soon and the fact that people just don’t have options.”

McDonald said that while it’s good for drug users to know what is circulating in the illicit drug supply with the use of test strips and drug checking so they can educate and advocate for themselves and their peers, it won’t make the supply less toxic.

“The reality is, many folks are still just going to have to use the drug regardless,” she said. “Which is just terrible.”