As It Happens5:59New research into the beetle’s butt could have positive implications for pest control

You’re probably familiar with the old saying about how cockroaches could survive an apocalypse. Well it turns out, they may have some company when everything else is gone: beetles.

“Beetles survive in places where few other organisms can survive, including the deserts,” biologist Kenneth Veland Halberg told As It Happens host Nil Köksal. “And to my knowledge, cockroaches still need to drink water.”

Scientists have long known that beetles can survive in extremely dry conditions — thanks to their unusual ability to suck water from the air through their rear ends.

Now Veland Halberg and colleagues from Copenhagen and Edinburgh have figured out exactly how they do that — and it could provide possible insights for better dealing with agricultural pests.

Their findings were published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) journal.

Up to 20 per cent of the world’s grain stores are lost to pests like beetles and other insects every year. Because they are able to survive in extremely dry conditions, they’re difficult to control.

Understanding how to interrupt their hydration on a molecular level could be the key, said Veland Halberg, who is also an associate professor of biology at University of Copenhagen.

“Controlling insect pests is unfortunately something we have to do,” he said. “And knowing about this mechanism and how critical it is to their survival, it gives the opportunity to affect that so they can be killed.”

Unique rectal design

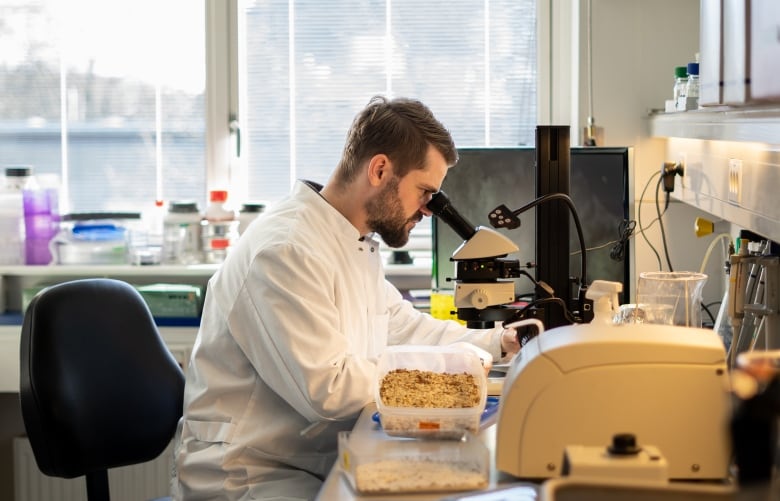

Veland Halberg and his colleagues studied the inner workings of the red flour beetle — which resembles those of many other beetle species — to figure out how they are sometimes able to go their entire lives without drinking water but stay hydrated.

The answer, he said, lies in the design of the beetle’s butt.

The beetle rectum does the same job as the rectum of most mammals or insects — absorbing remaining nutrients and water from bodily waste before it is expelled.

But beetles do it better than other species, he said. As a result, beetle feces is practically bone-dry.

“They just do it so efficiently that there’s no trace of water left, which is basically why they’re able to survive in extremely dry habitats,” said Veland Halberg.

Back-end hydration

A big part of how they do it has to do with the design of the beetle’s organs.

“Unlike the mammalian butts, the butt of the beetle has its kidneys closely applied to its rectum, and the entire structure is encased in what’s called the perinephric membrane,” he said.

“This whole structure allows the animal to generate really, really high salt concentrations in its kidneys — and yes, insects also have kidneys. And that basically draws water from high concentration to lower concentration,” he said. That means the beetle is basically able to extract all of the water from its feces and recycle the moisture back into itself.

The beetle can extract nearly all of the water out of the food it ingests — even something like flour, which has a relatively low water content of just one to two per cent.

It can also extract water from moist air — and not by mouth.

“It opens its rectum while the relative humidity of the water content of the atmosphere is quite high,” said Veland Halberg. It’s able to take that water and, again, almost fully absorb it and recycle it back into itself.

Finally, the beetle is able to generate its own internal water from the food they eat, something humans can also do through metabolic water production, which is essentially the process of your body absorbing water as food is metabolized.

“They just do it much more efficiently.” The beetle can also limit how much of that water they lose, Veland Halberg added, allowing them to “basically maintain water balance their entire life.”

Interrupting the process

Veland Halberg says now that he and his fellow researchers have figured out how the beetle manages to absorb all that water, scientists can now figure out how to interrupt the process — with potentially big implications for the agricultural industry.

“Given that this mechanism we’ve described is a beetle-specific mechanism, it opens up to the possibility that we can also design molecules that can fatally disrupt that mechanism, and we can then get a handle on controlling some of these beetle populations that we don’t want.”

This could allow humans to control the pest population without using pesticides that also harm humans and the environment.

“They’re major and devastating pests of food stores. So they’re really fascinating creatures — but they’re also existing in places we don’t want them,” said Veland Halberg.