After giving birth to her third child at 35-years old, Alexis Juliao began noticing blood in her stool.

“Everyone said to me, it’s hemorrhoids, you just had a baby,” the London, Ont., mother recalled. “Everyone explained it, or dismissed it, as being normal.”

But Juliao knew it wasn’t normal. And she knew she didn’t have any hemorrhoids.

What followed was a lengthy, frustrating process to figure out what was actually going on. For more than six months, Juliao kept experiencing the same bleeding, but most people simply brushed it off because of her age. She eventually took photos of the blood in her stool, prompting her physician to refer her for a colonoscopy.

Once Juliao finally had her scope — after nearly nine months of experiencing symptoms — she learned what was causing her bizarre bleeding while breastfeeding her youngest daughter in her hospital bed: a tumour.

She had Stage 1 colon cancer, despite only being in her mid-30s.

“I was actually relieved they had found what was wrong,” she said, “which very quickly turned into realizing the gravity of the whole situation.”

Juliao required major surgery to remove a roughly 30-centimetre stretch of her lower colon, had to take more than half a year off her work as a midwife to recover, and is now learning to live with life-altering changes to her digestive system.

While her situation remains rare, it’s increasingly clear to gastrointestinal specialists that colorectal cancer is on the rise among younger adults. The trend has been observed for years, in multiple countries including Canada, with no clear cause — though there are plenty of swirling theories that it could be linked to dietary or lifestyle changes in recent decades.

Whatever the reason, doctors are worried that younger patients may be slipping through the cracks of a medical system that screens older adults — and asking whether that needs to change.

“One of the challenges for young people is that, when presenting with symptoms, [they] are often told that they have hemorrhoids or some benign condition that’s causing bleeding,” said Vancouver-based colorectal surgical oncologist Dr. Carl Brown.

“But we feel strongly that all those patients, all of those people, should have [an] endoscopic evaluation to rule out cancer.”

A new health study out of the United States is revealing a worrying trend – colon and rectal cancer are on the rise in younger adults. Doctors say it’s happening in Canada too. No one is quite sure why, but some doctors are now asking if screenings should be made available to younger patients.

Colorectal cancer rising in people under 50 in U.S., Canada

New data from the American Cancer Society paints a stark picture: The incidence of colorectal cancer went up two per cent each year in people under 50 between 2011 and 2019, even though U.S. incidence rates have either dropped or stabilized for older adults who are eligible for screening programs.

Deaths have also gone up by one per cent each year since 2005 for people younger than 50, according to a report released this month, while advanced disease now appears to be increasingly common across the board.

“We know rates are increasing in young people, but it’s alarming to see how rapidly the whole patient population is shifting younger, despite shrinking numbers in the overall population,” said lead author Rebecca Siegel, the American Cancer Society’s senior scientific director for surveillance research, in a statement.

“The trend toward more advanced disease in people of all ages is also surprising.”

Top Canadian clinicians weren’t shocked by the data, with similar trends north of the border as well.

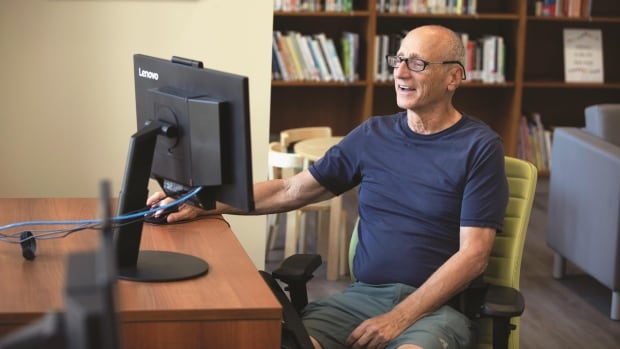

“As physicians, we need to be aware of these trends — and these alarming numbers — and have a lower threshold to refer [patients] on for investigation,” said Dr. Ian Bookman, medical director of the Toronto-based Kensington Screening Clinic, who said he’s been seeing more younger people with colorectal cancer, often at later stages, in recent years.

The typical age for patients, according to oncologist Dr. Christine Brezden-Masley, used to be around 65 years old and predominantly male. But in just the last few months, she recalled seeing three patients under 45 who progressed into advanced disease.

“We are all bewildered as to why younger patients are being diagnosed with [colorectal cancer], and some with advanced and more aggressive disease,” said Brezden-Masley, the medical director of the cancer program at Sinai Health System in Toronto, in an email exchange with CBC News.

One Canadian study, published in 2019 in the peer-reviewed Journal of the American Medical Association, found the incidence of colorectal cancer among younger Canadian adults has recently been rising by more than three per cent each year “and possibly accelerating.”

Brown, who’s also the lead for surgical oncology at B.C. Cancer, said many of the younger patients he sees have tried to get medical care for months, but were turned away because most physicians and caregivers didn’t realize they could be at risk.

“In some cases we’re seeing 30-year-old people with young families, and the emotional aspects, the challenges there, are intense,” Brown said.

Even if medical teams can cure these cancers — which they often can, Brown quickly added — the surgical treatments involved can dramatically alter someone’s life, since removing tumours often means removing portions of the colon, impacting bowel function and, in some cases, fertility or sexual function.

Bookman, in Toronto, said incontinence and lifelong reliance on ostomy bags — pouches used when stool is surgically redirected out through someone’s abdomen — are other potential impacts that can be particularly hard on young, working adults.

‘This is still a mystery’

Some scientists believe the rise in cases among younger adults may be linked to more consumption of processed meats and sugars and more liberal use of antibiotics in recent decades. Parsing a precise cause, though, is a difficult task.

“The leading hypothesis is that these kinds of factors influence the bacterial diversity within our gut, what we call the gut microbiome,” said Dr. Sharlene Gill, a professor of medicine at the University of British Columbia and a gastrointestinal medical oncologist with B.C. Cancer. That, in turn, may lead to chronic inflammation, which can hike the risk of cancerous cells developing.

Other researchers speculate that an increasingly sedentary lifestyle could be playing a role, or people eating less fruits and vegetables. Diet, alcohol use, and possibly other unknown, external factors may all be contributing, Brezden-Masley suggested.

“But this is still a mystery,” she added, “and shifting perhaps to earlier screening may be needed.”

Two years ago, the American Cancer Society — which put out the startling new U.S. statistics this month — dropped the recommended age cut-off for colorectal cancer screening to 45, down from 50.

Here in Canada, the conversation around the right age to get screened is ramping up as well.

What age should people be screened?

Multiple clinicians CBC News spoke to suggested Canada should be considering a lower cut-off, while also weighing the risks and benefits — alongside the need for more awareness of screening programs for all eligible adults.

“We’re investigating that in Canada, but we have not gone down that road at this point,” said Brown, in B.C. “One of the challenges is it takes a lot of resources to do screening programs, but we think the value of that is immense.”

So far, the provinces offering screening programs have stuck to a cut-off of 50 and up for average risk individuals, and typically only offer screening to those younger than 50 if they’re at a higher risk due to family history of the disease. (Northwest Territories, Nunavut and Quebec are still in the process of organizing screening programs, though screening tests are offered on a patient-by-patient basis.)

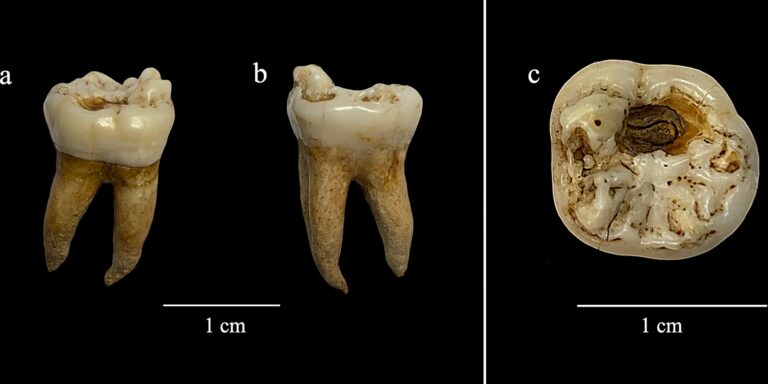

Colorectal cancer screenings usually involve one of two options: An at-home fecal immunochemical test, or FIT, is a screening tool that looks for hidden blood in fecal matter, which is typically offered when people don’t have major risk factors. When people are at a high risk, or actually displaying symptoms, a colonoscopy is typically offered.

Dr. Jill Tinmouth, the lead scientist for Ontario’s colon cancer screening program, stressed that there’s not yet sufficient evidence that the benefits of screening people under 50 would outweigh the potential harms that follow colonoscopies.

It’s an invasive test, involving a flexible scope inserted in the rectum, typically while a patient is under anesthesia. While the test is generally safe, and capable of spotting issues inside the colon that could be cancerous, Tinmouth said it comes with slight risks when physicians remove polyps — things like bleeding or puncturing the walls of the colon.

“We just want to reserve it for the cases where we really think the chances of finding something important are there,” she said.

Offering screenings to millions more Canadians could also be a “huge challenge” given the current backlog, Brown said.

Waiting lists, and wait times, for a colonoscopy ballooned in many regions in recent years as provinces struggled to catch up with the number of procedures cancelled or delayed during the COVID-19 pandemic. One federal estimate suggests 540,000 Canadians might have missed their colorectal cancer screening between April and the end of June in 2020.

As the country plays catch-up, Brown worries primary care providers are struggling to even get those already eligible through the screening system.

“When they know that the wait list for a colonoscopy may be a year, they look for other ways of investigating and managing people rather than sending them for what they think maybe a few really long wait,” he said.

Need for ‘increased awareness’

Whether or not Canada follows the U.S. on lowering screening cut-offs in the future, several physicians said both Canadians and their family doctors or other primary care providers need to be more aware that, while still rare, colorectal cancer is a rising threat to the health of younger adults.

Elizabeth Holmes, senior manager of health policy at the Canadian Cancer Society, said it’s important to be upfront about changes in your bowel habits, and push to have medical assessment to rule out serious illness.

“Trust yourself that you know what is right for your body,” she said. “If there’s something wrong, it might not be something serious, like colorectal cancer, but it’s still something that is bothering you.”

Juliao, the Ontario mother of three, wonders what could have happened if she’d given up on getting a colonoscopy.

“It could’ve been much more devastating,” she said.

Cancer specialists are bracing for a wave of patients suffering from more advanced disease due to delays in both screening and diagnostic testing during the pandemic.

But even her Stage 1 diagnosis was life-altering. The first year of her recovery after surgery was challenging, since the loss of a portion of her colon led to major changes in how her digestive system works.

Juliao began suffering from pain and bloating, and realized her body simply can’t handle certain foods anymore, from garlic to certain types of beans.

“I have to go to the bathroom much more frequently,” she added. “It’s not something we really talk about in our society but initially after the surgery, I had to poop 10 to 12 times a day. That’s not something you can manage with work, with having kids. I couldn’t really go anywhere.”

Like many Canadian clinicians, she’s now calling for more awareness of the risks facing younger adults. Otherwise, she warned, more people like her could have their lives upended by a cancer no one wants to talk about.

“It’s about trusting ourselves, and listening to ourselves,” Juliao said. “And for care providers, it’s about trusting their patients.”

Colorectal cancer symptoms to watch for

- Diarrhea, constipation, or other persistent changes in bowel habits or stool consistency.

- Blood in your stool or bleeding from the rectum.

- Unexplained weight loss.

- Ongoing abdominal pain, gas, or cramping.

- Feeling like your bowels don’t fully empty out.

- Weakness or fatigue.