After three years, the La Niña weather phenomenon that increases Atlantic hurricane activity and worsens western drought is gone, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) said Thursday.

The globe is now in what’s considered a “neutral” condition and probably trending to an El Niño in late summer or fall, said climate scientist Michelle L’Heureux, head of NOAA’s El Niño/La Niña forecast office.

La Niña is a natural and temporary cooling of parts of the Pacific Ocean that changes weather worldwide. El Niño is the opposite, where part of the Pacific Ocean warms.

When there’s a La Niña, there are more storms in the Atlantic during hurricane season because it removes conditions that suppress storm formation. Neutral or El Niño conditions make it harder for storms to get going, but not impossible, scientists said.

Hurricane Fiona devastated Atlantic Canada

Over the last three years, the U.S. has been hit by 14 hurricanes and tropical storms that caused a billion dollars or more in damage, totalling $252 billion in costs, according to NOAA economist and meteorologist Adam Smith said. La Niña and people building in harm’s way were factors, he said.

In Canada, post-tropical storm Fiona caused $660 million in insured damage, according to an initial estimate by Catastrophe Indices and Quantification Inc.

The storm made landfall in Nova Scotia on Sept. 24 and tore through the region. More than 500,000 customers in the Maritimes lost power.

WATCH | Fiona washes away homes, displaces residents in Port aux Basques, N.L.

Multiple homes have been washed away in Port aux Basques, N.L., after post-tropical storm Fiona barrelled through the tiny Newfoundland outport. The storm caused much damage in the town and also took the life of a woman who was swept out to sea.

The hurricane brought winds of more than 100 kilometres per hour, torrential rainfall, flooding, brought down trees, and resulted in several deaths, the Insurance Bureau of Canada said.

At least 20 homes were washed away into the ocean, mainly in Port aux Basques, N.L.

“It’s over,” said research scientist Azhar Ehsan, who heads Columbia University’s El Niño and La Niña forecasting. “Mother Nature thought to get rid of this one because it’s enough.”

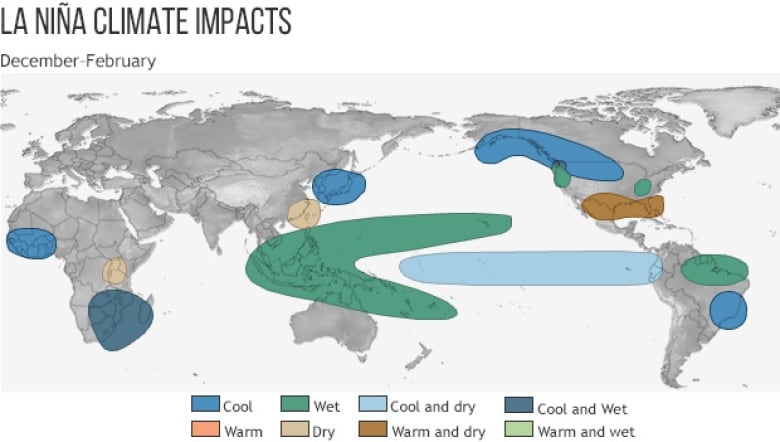

La Niña tends to make Western Africa wet, but Eastern Africa, around Somalia, dry. The opposite happens in El Niño with drought-struck Somalia likely to get steady “short rains,” Ehsan said. La Niña can bring wetter conditions for Indonesia, parts of Australia and the Amazon, but those areas can become drier during an El Niño, according to NOAA.

El Niño could mean more heat waves for India and Pakistan and other parts of South Asia and weaker monsoons there, Ehsan said.

Long-lasting La Niña

This particular La Niña, which started in September 2020 but is considered three years old because it affected three different winters, was unusual and one of the longest on record. It took a brief break in 2021 but came roaring back with record intensity.

“I’m sick of this La Niña,” Ehsan said.

L’Heureux agreed, saying she’s ready to talk about something else.

The few other times there’s been a triple-dip La Niña, it’s been after strong El Niños. But that’s not what happened with this La Niña, L’Heureux said. This one didn’t have a strong El Niño before it.

Even though this La Niña has confounded scientists in the past, they say the signs of it leaving are clear: Water in the key part of the central Pacific warmed to a bit more than the threshold for a La Niña in February, the atmosphere showed some changes along the eastern Pacific near Peru, and there’s already El Niño-like warming brewing on the coast, L’Heureux said.

Think of a La Niña or El Niño as something that pushes the weather system from the Pacific with ripple effects worldwide, L’Heureux said. When there are neutral conditions like now, there’s less push from the Pacific. That means other climatic factors, including the long-term warming trend, have more influence in day-to-day weather, she said.

Without an El Niño or La Niña, forecasters have a harder time predicting seasonal weather trends for summer or fall because the Pacific Ocean has such a big footprint in weeks-long forecasts.

El Niño forecasts made in the spring are generally less reliable than ones made other times of year, so scientists are less sure about what will happen next, L’Heureux said. But NOAA’s forecast said there’s a 60 per cent chance that El Niño will take charge come fall.

There’s also a five per cent chance that La Nina will return for an unprecedented fourth dip. L’Heureux said she really doesn’t want that but the scientist in her would find that interesting.