The Environmental Protection Agency headquarters is seen in Washington, D.C., U.S., January 19, 2020.

Lucy Nicholson | Reuters

The Environmental Protection Agency on Tuesday proposed the first nationwide restrictions on so-called “forever chemicals” in drinking water after discovering the compounds are more dangerous than previously known — even at undetectable levels.

The chemicals, known as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, have been voluntarily phased out by U.S. manufacturers. But they are resistant to breaking down in the environment and can linger in the human body when consumed. As a result, most people in the U.S. have been exposed to PFAS and have the chemicals in their blood, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Since the 1940s, the chemicals have been used to make products waterproof, stickproof and stain-resistant, and they can be found in food packaging, cookware, clothing and firefighting foam, among other things. The chemicals have been linked to health problems including certain cancers, liver damage and low birth weight.

The Environmental Working Group, an environmental organization, has found 41,828 industrial and municipal sites that are known to produce, use or are suspected of using PFAS, with some of the highest levels found in the cities of Miami, New Orleans and Philadelphia.

The EPA’s proposed standards cover six PFAS that have polluted drinking national water supplies. The proposal would regulate PFOA and PFOS as individual contaminants and would regulate four other PFAS — PFNA, PFHxS, PFBS and GenX chemicals — as a mixture.

For PFOA and PFOS, the agency proposed a binding drinking water limit of four parts per trillion per chemical. And for the rest, the EPA proposed a binding limit based on a hazard index designed to address the cumulative impact of the chemicals.

The agency said it expects to finalize the regulation by the end of the year. The EPA said, if fully implemented, the rule will prevent thousands of deaths and reduce tens of thousands of PFAS-attributable illnesses.

“Communities across this country have suffered far too long from the ever-present threat of PFAS pollution,” EPA Administrator Michael Regan said in a statement. “EPA’s proposal to establish a national standard for PFAS in drinking water is informed by the best available science, and would help provide states with the guidance they need to make decisions that best protect their communities.”

The regulation would also require public water systems to monitor for the chemicals, notify the public and reduce PFAS contamination if levels exceed the proposed regulatory standards.

“Today’s proposal is a necessary and long overdue step towards addressing the nation’s PFAS crisis, but what comes next is equally important,” said Jonathan Kalmuss-Katz, an attorney at Earthjustice.

“EPA must resist efforts to weaken this proposal, move quickly to finalize health-protective limits on these six chemicals and address the remaining PFAS that continue to poison drinking water supplies and harm communities across the country,” Kalmuss-Katz said.

The EPA was first alerted to the presence of PFAS in drinking water in 2001 but over the years has failed to set a nationwide legal limit. Last year, the agency issued health advisories that set health risk thresholds for the chemicals close to zero, replacing 2016 guidelines that set a higher threshold.

Representatives of U.S. chemical companies, such as the American Chemistry Council, had opposed the Biden administration’s designation of PFAS chemicals as hazardous and argued the rule was costly and ineffective.

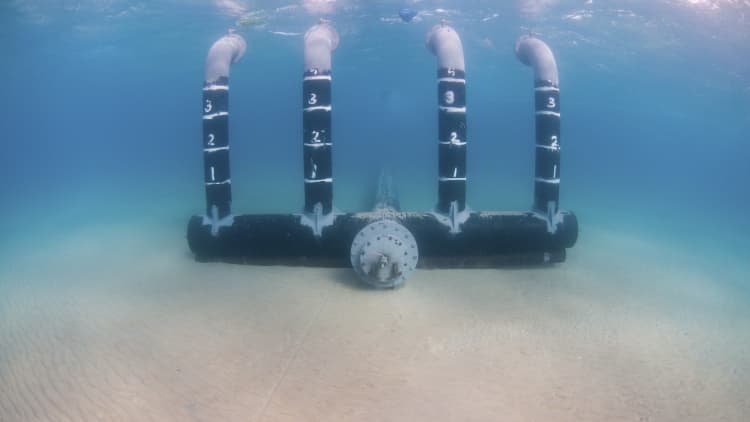

The agency last year also invited states and territories to apply for $1 billion under the bipartisan infrastructure law to address PFAS in drinking water, specifically in disadvantaged communities. The grant funding will provide technical assistance, water quality testing, contractor training and installation of centralized treatment technologies and systems.