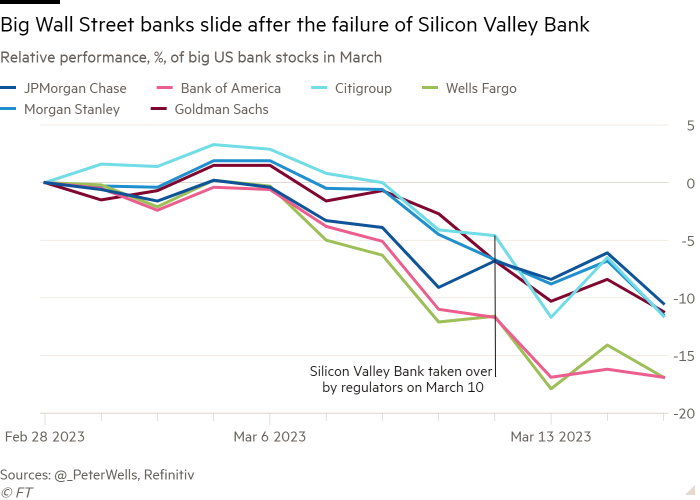

The six largest Wall Street banks have lost almost $165bn in market capitalisation this month, or 13 per cent of their combined value, hit by worries over Credit Suisse’s financial strength and the fallout from the largest US bank failure since 2008.

Shares of Citigroup and Morgan Stanley suffered the biggest sell-off on Wednesday, while Bank of America shares fell to a more than two-year low. Investors said the three banks plus Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase and Wells Fargo are being hurt by predictions that profits will be squeezed.

Investors do not think the largest US lenders will suffer the same fate as Silicon Valley Bank, which was forced to sell a portfolio of securities at a $2bn loss after customers pulled out their cash. Indeed, the bigger banks are experiencing an influx of deposits as customers seek safety amid fears over the health of smaller regional players.

But that has not protected them from a sharp sell off amid fears they will have to pay higher rates to depositors, hurting profits, while also facing the prospect of tougher regulation following the recent turmoil and rising loan delinquencies if the US falls into a recession.

Jason Goldberg, banking analyst at Barclays said: “The market never likes uncertainty. And there’s just a lot of uncertainty right now. The ultimate fallout . . . is still trying to be understood.”

One large investor in financial stocks said: “It is reasonable to expect that the regulatory rules will change and that the profile of the bank is going to change if they’re required to hold more liquidity and more capital. All that is going to increase costs and reduce profitability.”

Investors are also cutting the value they ascribe to the assets held by the nation’s largest banks. In early 2022, the KBW Index, which tracks 22 large banks, traded at an average multiple of 1.5 times book value. That multiple fell below 1 last week for the first time since 2020.

Banks with large trading arms also suffered on Wednesday from concerns about their potential exposure to Credit Suisse, after investors wiped almost a quarter off the Swiss lender’s shares.

“It’s kind of a repeat of the 2011 European financial crisis, where all of a sudden people are wondering, who’s got counterparty exposure?” said Oppenheimer analyst Chris Kotowski, referring to the eurozone debt crisis 12 years ago which shook confidence in the banking system.

The share price falls at the big banks are much smaller on a percentage basis than the dramatic collapse in midsized bank stocks. The Fed has already said it is considering tougher rules for the medium-sized banks, which would cut into profits. The KBW regional bank index is down 19 per cent since the start of March.

Bank stocks are also being hit by a belief that lenders will have to start increasing the interest they pay to depositors. For many financial institutions, the gap between what they charge for loans and what they have to pay on deposits, known as net interest income, has buoyed earnings at a time when mortgage lending has fallen sharply and delinquencies on auto loans are rising.

In a note on Wednesday, UBS wrote of the largest banks: “While the bank stock performance is stabilising a little throughout the day as investors get more comfortable on going concern risk, now investors are also concerned about deeper NII cuts from greater deposit outflows.”

Analysts watching the sell-off in the wake of SVB’s collapse speculated that the blanket sale of financials was down to algorithms used by large investors to screen for financial similarities to the failed California bank.

Those might include large paper losses on their bond portfolios — which are stuffed with securities that have declined in value as the Fed has raised rates — and a high reliance on large depositors who are not ordinarily covered by federal insurance and are more likely to move their money.

“The hedge funds and the bears did big screens with data to see who has high unrealised losses,” said Rich Repetto, an analyst at Piper Sandler.

Funds used that data to identify those banks that would “take a hit relative to the equity capital that they have” if they were forced to sell securities at a loss, regardless of the strength of their business.

Still, some asset managers who invest in the large banks said they believed the sell-off was “collateral damage” from SVB, and were prepared to increase their holdings in banks if the sell-off made prices more attractive.

The federal regulators’ decision to guarantee all deposits, including those above the usual $250,000 cut off, at SVB and Signature, which also collapsed over the weekend, helped slow down the sell-offs but did not stop them.

The whole situation “is potentially creating opportunities”, said a person familiar with the investment strategy of one large asset manager. “Before we start jumping in with two feet, we have to be comfortable that the contagion risk is basically behind us.”