The Current15:57Tackling rising syphilis cases across Canada

READ TRANSCRIBED AUDIO

There has been a sharp increase in the number of babies born in Canada with syphilis, an infection that one doctor says “can be particularly devastating in pregnancy.”

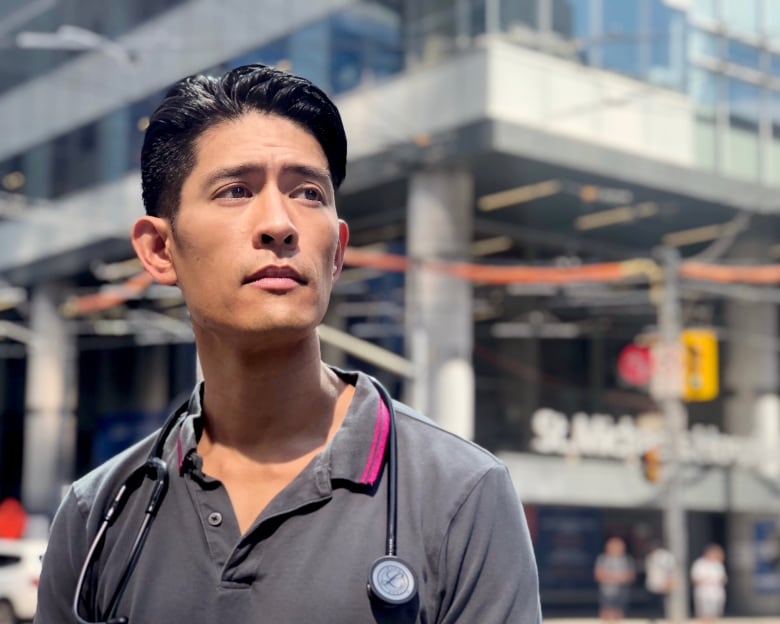

“It can lead to outcomes such as fetal demise … or stillbirth,” said Dr. Darrell Tan, an infectious disease physician at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, and the Canada Research Chair in HIV Prevention and STI Research.

“And then in a child [born with syphilis] there can be many, many manifestations … it can affect organ systems like the brain, the bones and joints, virtually any organ system in the body,” he told The Current’s guest host Mark Kelley.

Figures from the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) show that there were seven cases of congenital syphilis in 2017, but 96 cases in 2021 — an increase of 1,271 per cent over four years. A similar trend has been observed south of the border.

Thirty newborns in Manitoba have been infected with congenital syphilis through the first eight months of 2020, according to information obtained by the Opposition NDP.

That increase is tied to rates of infection within the general population, which have been increasing steadily for the past decade. Last month, health authorities in B.C. revealed a 27 per cent increase in cases from 2021-22.

Historically, the disease has disproportionately affected men who have sex with men (MSM), but Dr. Troy Grennan said B.C. figures show a shift in 2022.

“For the first time the majority — so more than 50 per cent — of the new cases we’re seeing [in B.C. are] in non-MSM populations,” said Grennan, lead physician at B.C.’s Centre for Disease Control’s sexual health programs.

“One of the key challenges around that is that we’re seeing increasing cases in folks who are capable of getting pregnant,” he said.

Experts say there’s likely multiple factors behind the increase, including reduced condom use — a 2020 survey found that seven in 10 of Canadian respondents don’t use condoms. Some experts also point to the increasing availability of routine testing, and the idea that numbers are up in part because more infections are being detected.

Tan said the spread into new demographics “may simply be a numbers game.”

“When you have cases, case rates that are going up to this degree, you start to see it spread beyond just the core sexual networks that had traditionally been involved,” he said.

If caught early, an infection can be easily treated with antibiotics. But Tan said that structural inequalities, such as racism and the legacy of colonization, can also “impact people’s willingness or perhaps ability to access care at earlier stages — where we can maybe nip things in the bud.”

Diverse symptoms, or none at all

Syphilis can present a diverse range of symptoms, which can complicate catching the infection early, Tan said.

On initial infection, an ulcer can appear at the part of the body that was exposed, he said. But that ulcer might be painless, and perhaps on a body part where it’s hard to see, such as the vagina or rectum.

In other cases, the infection sparks a fever or rash. These symptoms may prompt someone to seek medical attention, but they can also be mistaken for many other illnesses.

“The most confusing and frustrating thing is that it can cause no symptoms at all, and people can contract it without even realizing it,” Tan said.

If left untreated, the infection can have serious implications, including neurological problems, organ damage, loss of vision and even death.

Vaccine work ‘not very far along’

Research into syphilis is complicated by the fact that the “bacterium is very difficult to work with,” said Caroline Cameron, one of the few researchers studying the infection in Canada.

“We really don’t understand how it works, how it infects a person or ways to appropriately combat it, or prevent that infection,” said Cameron, a professor in the department of biochemistry and microbiology at the University of Victoria.

While Cameron said she was drawn to those challenges, they’ve dissuaded many other researchers — but that is slowly changing.

“We are starting to get more philanthropic organizations who are providing funding for research and we’re starting to see more people join the field, which is what is really needed in order to get those innovative research programs going,” she said.

The aim is to produce better medical interventions, perhaps even a vaccine for syphilis, she said. But the difficulties in studying it mean that, globally, the research is “not very far along,” she said.

“Conservative estimates [for a vaccine] are five to 10 years away. But we really need more people to join the field to expand the research population,” she said.

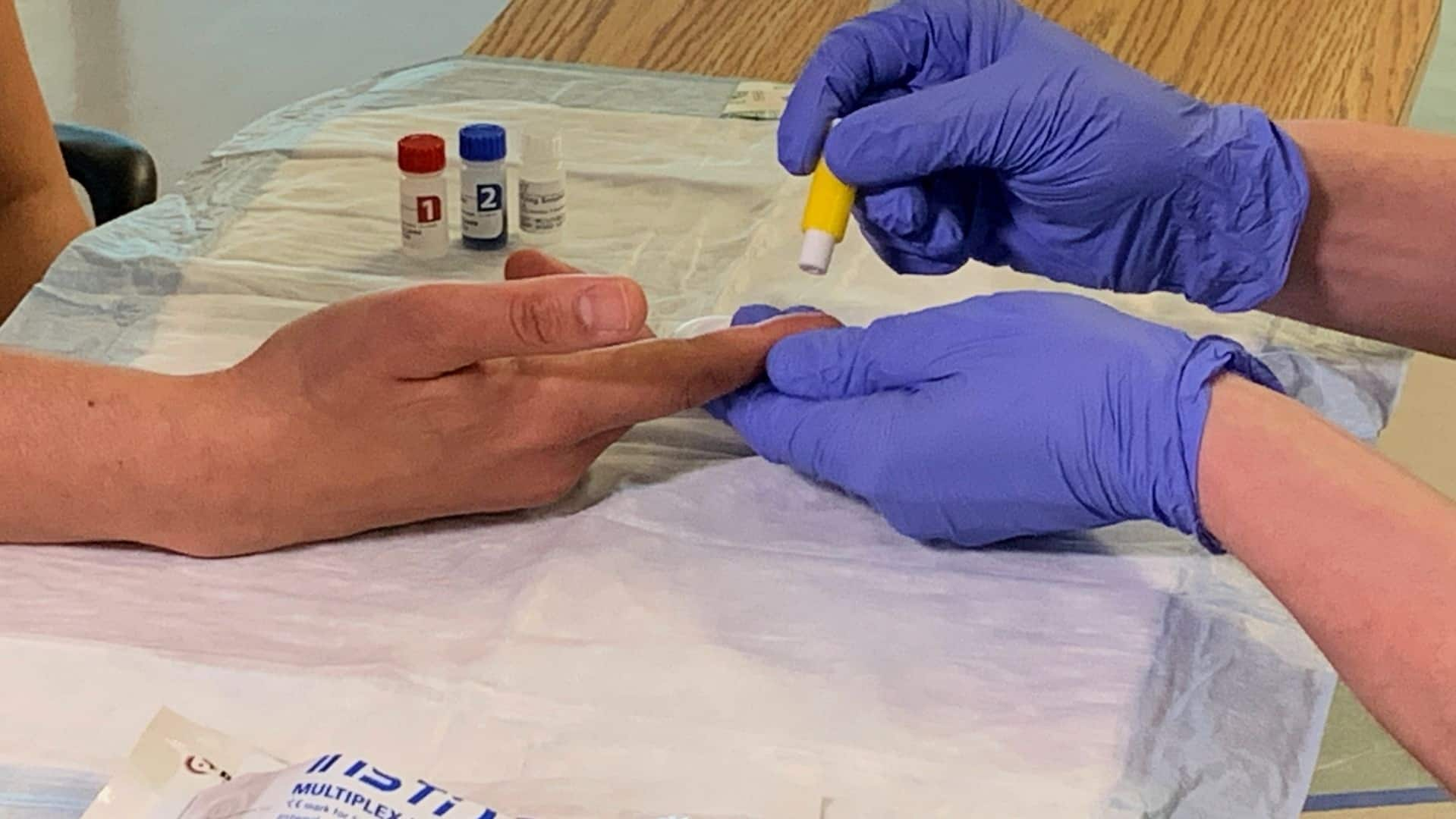

Doctors and outreach workers are hopeful wider use of a new rapid test for syphilis could help slow the spread of the dangerous sexually transmitted infection.

Get tested, get treated

Syphilis can be detected by a simple blood test “that can be ordered by any clinician relatively easily,” but the challenge is often knowing when to request it, Tan said.

He suggested people who are sexually active with multiple partners should seek routine STI testing, as frequently as every three months.

PHAC guidelines stipulate universal screening for syphilis during the first trimester of pregnancy. For those at greater risk of exposure, the guidelines suggest a repeat screening at 28 to 32 weeks, and again at delivery.

However, problems can arise for “folks who unfortunately don’t access pre-natal care,” he said.

“We do have very effective treatments … simply two or more injections of plain old penicillin,” Tan said.

“But if folks are not accessing care earlier in the course of infection … then we can see cases continue to spiral as we’ve seen, and have a hard time getting control of the epidemic.”