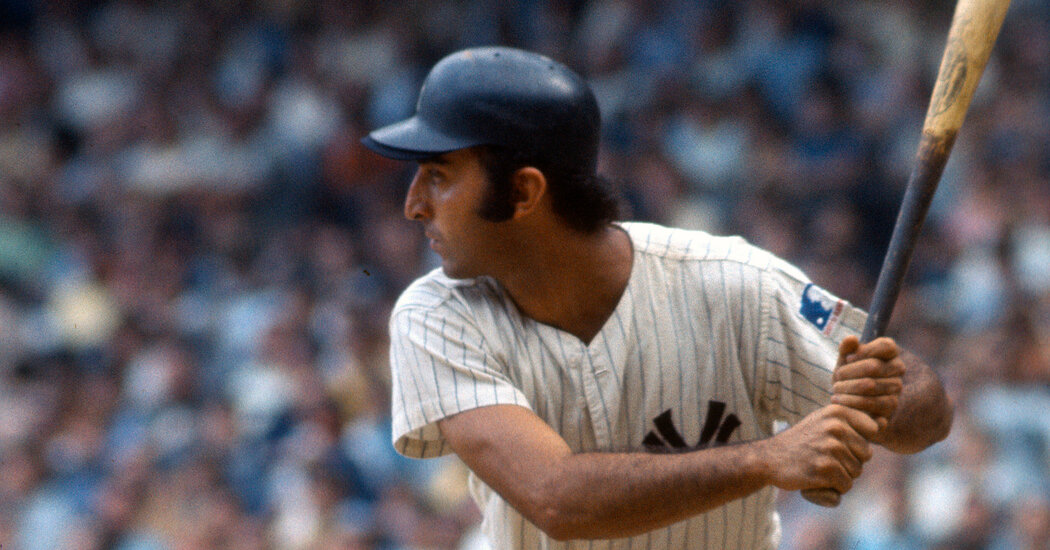

Joe Pepitone, who won three Gold Gloves at first base and played in two World Series for the Yankees but who may be best remembered for his hair and his high jinks, has died at his home in Kansas City, Mo. He was 82.

His son Bill confirmed the death. He said his sister, Cara Pepitone, who had lived with their father, had found him dead on Monday morning. The cause was unknown, he said, but it appeared to have been a sudden event, like a heart attack. The Yankees also announced his death in a statement.

Pepitone was a fan favorite in New York. They called him Pepi, a local boy who came to the Yankees in 1962 with a sweet, compact, left-handed swing, a slick glove and the personality of an irrepressible joy rider from da naybahood.

His renegade nature would eventually cost him. He earned a reputation for wildness and unreliability, and in the 1980s, long after his career had ended, he went to prison on a drug charge. But at the start it was big fun.

A cutup in the locker room, a jabberer with the fans, Pepitone wore his hair pouffy and long; he was famously the first Yankee to bring a hair dryer into the clubhouse and supplemented his coiffure with toupees. And he led the life of a late-night social prowler, spreading money around, chasing women and hitting notorious glam-and-trouble spots like the Copacabana. Before the arrival in New York of Joe Namath, he was, well, a poor man’s Joe Namath.

Like Namath, the brash Jets quarterback christened Broadway Joe who in 1969 promised New York its first Super Bowl winner and then made it happen, Pepitone could play. A slender kid with surprising power, he also had the arm, speed and judgment to play more than 400 games in center field during his 12-year career.

In his second season, he displaced the Yankees’ longtime first baseman Bill Skowron, and with Mickey Mantle and Yogi Berra aging and Roger Maris’s best years behind him, Pepitone seemed poised to become the focus of the next-generation lineup. From 1963 to 1965, he made three consecutive All-Star teams, belting 27 home runs in 1963, 28 in 1964, 18 in 1965 and a career-high 31 in 1966.

But this turned out to be a period of grim transition for the Yankees, from dominant club to also-ran. After winning 10 World Series in the previous 16 years, the Yankees lost in a sweep to the Dodgers in 1963 — Pepitone mishandled a throw for a three-base error that cost the Yankees the final game — and in seven games to the Cardinals in 1964.

The team wouldn’t return to the Series until 1976, and Pepitone, whose own performance leveled off, never did. His Yankee teams finished no higher than fifth through 1969, after which he completed his big-league career in the National League, playing for the Houston Astros, the Chicago Cubs and briefly in 1973 for the Atlanta Braves.

He socked 27 homers again for the Yankees in 1969 and hit .307 in more than 400 at-bats for the Cubs in 1971, but after 1966 he never drove in more than 70 runs in a season. Overall, he hit 219 home runs, with a career average of .258.

For most of his career, Pepitone undermined his own gifts with his rambunctious and self-destructive behavior. He had money problems and marital problems. His night life began after night games; he drank with and without his teammates and was no stranger to drugs. He claimed at one point to have turned Mantle and Whitey Ford on to marijuana, and in an interview in Rolling Stone magazine in 2015, he recalled that when he was with the Cubs, fans in the bleachers would throw packets of joints and cocaine at him in the outfield, and he would hide them in the ivy that covered the stadium wall.

“Used to be I was always the first person at the ballpark, and the first one to leave; next thing you know, people are wondering why I’m hanging out at the ballpark so long,” Pepitone told Rolling Stone. When the manager, Leo Durocher, asked him what he was doing hanging around, he would say he was going to get a rubdown from the trainer.

“Then I’d be out in center field with my shorts on, looking through the ivy to find my dope,” he said. “I loved Chicago!”

Joseph Anthony Pepitone was born in Brooklyn on Oct. 10, 1940, to William and Angelina (Caiazzo) Pepitone. He grew up there in a rugged neighborhood of largely Irish American and Italian American working-class families. His mother worked in a clothing factory; his father was a pugnacious construction worker who was sometimes called Willie Pep after the boxer of that name and who was fond of using his fists to settle disputes both outside and inside the house.

In his forthright 1975 autobiography, “Joe, You Coulda Made Us Proud,” written with Berry Stainback, Pepitone said he had a love-hate relationship with his father, whom he described as displaying a volcanic temper but also a passionate devotion to his family.

Pepitone was introduced to baseball by his mother’s brother, Louie Caiazzo, who was called Uncle Red. Caiazzo spent hours with Joe throwing and catching and making him field grounders. Joe developed into a star in neighborhood stickball, in pickup games in Prospect Park and at Manual Training High School (later John Jay High School and now a building known as the John Jay Educational Complex, housing three small high schools). In high school, he was known for clubbing long home runs.

He also played for a semipro team sponsored by Nathan’s Famous hot dogs, playing so well that professional scouts began showing up to watch him play.

In the spring of 1958, everything nearly went awry. A high school senior at the time, Pepitone was at his locker at Manual Training when, as he described it in his memoir, a schoolmate was fooling around with a loaded gun and accidentally shot him in the gut, just below the rib cage. The wound was serious enough that a priest arrived to perform last rites while Joe was waiting for the ambulance.

He was lucky, however; the bullet missed all his vital organs, and after surgery and 12 days in the hospital, he went home. A few days later, his father, who had had a heart attack, died at 39. That August, the Yankees signed Pepitone for $25,000, though the shooting most likely deprived him of a bigger bonus.

Pepitone played briefly in Japan in 1973 and wrote a whiny article for The New York Times about his treatment there; hardly anyone spoke English, he complained, “and at my apartment, I swear the door was 4 feet 5 inches high.”

He played some professional softball, was in the bar business for a time and in the early 1980s worked briefly for the Yankees as a hitting coach. In 1985, he was riding in a car with two other people when the police stopped them for running a red light and found drugs — cocaine, heroin and quaaludes — and a loaded handgun in the car.

Pepitone was convicted on misdemeanor counts of possession of drugs and drug paraphernalia and served about half of a six-month sentence.

“I find it particularly sad,” the judge, acting Justice Allan Marrus of State Supreme Court, told him at his sentencing, “when someone who graced New York in Yankee pinstripes will now have to serve his time with the New York Department of Correction in their prison stripes.”

Pepitone later worked in public relations for the Yankees and mostly stayed out of trouble, though he did plead guilty to drunken driving after losing control of his car in the Midtown Tunnel in 1995. He was married and divorced three times.

In addition to his children Bill and Cara, Pepitone is survived by another son, Joseph Jr.; two more daughters, Eileen and Lisa; two brothers, Vincent and William; several grandchildren; and at least one great-grandchild. He had recently moved from Long Island to Kansas City to be closer to Cara.

Still, he remained a vivid and mostly fond memory for Yankee fans of a certain vintage. His name was invoked on a variety of television shows, including “The Golden Girls,” “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” “The Sopranos” and “Seinfeld.”

For many in the game — players, coaches, sportswriters and even umpires — Pepitone was a lovable if self-centered, entertaining if exasperating, hugely talented if hugely troubled guy.

“I wish I could buy you for what you’re really worth,” Mantle once said to him, according to the website Baseball-Almanac.com, “then sell you for what you think you’re worth.”

Alex Traub contributed reporting.