As the premiers and the federal government continue to battle over health-care funding, leading doctors and experts say that while more government money is needed, the way health care is delivered in Canada also needs to change.

The issue is dominating the national conversation now as patients find themselves let down by a shortage of doctors and nurses, overwhelmed pediatric hospitals and a backlog in necessary but elective surgeries.

The Children’s’ Hospital of Eastern Ontario (CHEO) recently had to accept staffing help from the Canadian Red Cross as it struggles with a surge in hospitalizations caused by respiratory viruses like influenza, RSV and COVID-19.

Alex Munter, CHEO’s CEO, said the hospital has just experienced its “busiest May, June, July, September, October and November” in its 50-year history.

The Alberta Children’s Hospital in Calgary is facing a similar situation. It set up a heated trailer next to its emergency room as it continues to operate beyond 100 per cent capacity.

“We are seeing a greater number of children significantly unwell, requiring hospitalization at a given time in a short period, than we have probably ever seen before,” said Dr. Stephen Freedman, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Calgary.

“Our biggest challenge in our emergency right now in Calgary is often space to see kids. We’ve started therapy, but there’s nowhere for them to move to. So they’re stuck in the emergency department for 24, 36 hours.”

Experts say that hospitals and family practices in Canada were built to operate at almost full capacity all the time. When the system experiences spikes in need, doctors and nurses simply work longer hours to meet the demand. But the system was operating over peak capacity for a long time during the pandemic — and doctors and nurses started burning out.

The Canadian Medical Association (CMA) surveyed its members and found 53 per cent of doctors were reporting burnout in 2021, compared to 30 per cent in 2017. A similar survey of 5,200 nurses by the Registered Nurses Association of Ontario found more than 75 per cent of nurses qualified as burnt-out in 2021.

“It is like driving around with only $5 in the gas tank, knowing that winter is here, knowing that a day that’s minus 30 is just around the corner, but then not changing the approach and idling and then running out of gas,” said CMA president Dr. Alika Lafontaine.

Dr. Lafontaine said that if doctors and nurses continue to burn out on the job, the system will deteriorate further.

Canada has a well-documented shortage of doctors and nurses — a problem made worse, doctors say, by the increasing administrative burden they face.

The CMA says family physicians work an average of about 52 hours a week, but only spend 36 hours caring for patients. The rest of their time is taken up by administration and other non-medical tasks.

The same is true of other doctors. Medical residents work about 66 hours a week but see patients for 48. Specialists work more than 53 hours a week but see patients for just 36. Surgeons work almost 62 hours a week and only see patients for about 46.

“It has nothing to do with their individual resiliency or high capacity or compassion or commitment to patient care, but it’s because we find ourselves in a health-care system that’s broken,” said Dr. Rose Zacharias, president of the Ontario Medical Association.

Dr. Zacharias said the administrative burden has “grown astronomically,” extending beyond paperwork to arguing for beds in hospitals and arranging emergency transfers.

The Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions says its members are similarly streamed into administrative tasks that require them to manage staff, arrange transfers, fill out reports and even perform some cleaning duties.

“The reason why we’re in the situation that we’re in, I think, is because over the past couple of decades we’ve been really focused on cost-cutting as a solution to our health-care problems,” said Dr. Lafontaine.

“Provincial and territorial governments have implemented approaches that have really focused on the cost per volume of procedures and appointments and … as a result we’ve lost a lot of the bandwidth that we used to have when it came to spikes in demand.”

A very political debate

While these problems persist, the debate between the premiers and the federal government has been largely about money.

Canada’s premiers say the federal government is only paying 22 per cent of the cost of providing health care. They want that boosted to 35 per cent — an increase of $28 billion to the $45.2 billion Canada Health Transfer (CHT) starting this year — and for the CHT to increase by six per cent annually after that.

The federal government said that while the CHT only covers 22 per cent of health-care costs, taxation powers transferred to the provinces in 1977 to pay for health care — and funding for things like mental health services, home care and long-term care — bring the federal government’s share up to as much as 38.5 per cent.

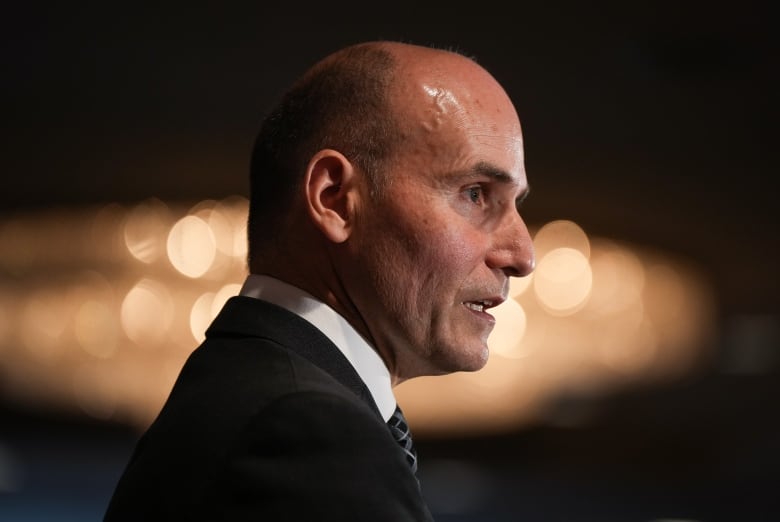

Federal Health Minister Jean-Yves Duclos said he is willing to bring more money into the system — but only if the provinces agree to system reforms to improve outcomes.

Doctors and administrators working in the health-care system say that reform is essential if any new money is going to improve delivery — and they have plenty of ideas about the changes that need to be made.

Relieving the administrative burden

The addition of administrative staff specifically tasked with non-medical responsibilities could help, but that won’t happen without long-term, predictable funding that would come from a new health deal between the provinces and the federal government, Munter said.

“Five years ago we could put up a one-year contract, people would take it and then hope to be able to find a full-time job after. That’s not possible anymore,” he said. “We’ll get zero applicants for those kinds of positions.”

“We have to hire people permanently. And … a lot of the funding that comes and goes into the health system is temporary money.”

An investment in community care, palliative care, home care would help alleviate strain on the hospitals.– OMA President Dr. Rose Zacharias

The federal government and the provinces have agreed to streamline how health information is shared in Canada, but doctors say that effort needs to speed up to take some of the administrative burden off doctors and nurses.

“Our digital integration is very poor,” said Dr. Zacharias. “Doctors document inside software that doesn’t communicate with hospital software, or pharmacist software, or COVID vaccination software.

“Doctors are spending a lot of time gathering the relevant data … and this is incredibly burdensome, and that burden has grown over time.”

Experts say that while it takes years to reverse a shortage of doctors and nurses, quickly recognizing the foreign credentials of doctors and nurses already living in Canada would boost their numbers now without poaching health-care workers from abroad.

“We do have hundreds of doctors here in Ontario that have trained elsewhere that don’t have a Canadian licence,” said Dr. Zacharias. “If we were able to … put these physicians through those three months of a practice-ready assessment … we could see hundreds of doctors in the system by the spring.”

Fixing the problem in the longer term is harder because it takes about five to 10 years to train a doctor in Canada. That timeline demands long-term, predictable funding, doctors say.

“We shouldn’t be just thinking now. We should be thinking, okay, what’s going to be our capacity need in 10 or 20 years? And we should be building now for 10 years from the future and in 10 years we should be planning for 10 years down the road again,” said Freedman.

Changing how health care is delivered

The burden on the hospital system could be significantly reduced, doctors say, if more health care services were delivered outside of a hospital setting.

Increasing the delivery of non-hospital health services would require additional family doctors with lower administrative burdens. It also would require changes to how family practices work, doctors say.

“One [way] is to get doctors into teams of other allied health-care professionals, doctors working alongside nurse practitioners, physician assistants … psychotherapists, social workers, discharge coordinators, pharmacists [and] rehab therapists,” said Dr. Zacharias.

“All of these allied health-care professionals on the team of a physician could really offload a lot of the responsibility that often patients look to the family doctor especially for.”

Improved health care at the primary level, doctors say, would mean fewer people being sent to hospital because of the sheer volume of work family doctors do. The Alberta College of Family Physicians said that in 2020, 70 per cent of all health care visits in Canada were to a family doctor.

Doctors say that moving elective surgeries out of hospitals and into surgical centres would also help free up operating rooms for more urgent surgeries. They also say that moving palliative care out of the hospital setting would free up beds and staff.

“Hospitals are filled with people who no longer need acute hospital attention, but they’re there because they can’t be safely discharged into the community or a long term care or hospice bed,” said Dr. Zacharias. “An investment in community care, palliative care, home care would help alleviate strain on the hospitals.”

Solving Canada’s health-care crisis, experts say, requires more than just money. It requires a new way of doing things.

“I don’t feel like crisis management, cash influxes … I mean, no one’s going to turn that down, but I think the bigger picture is, we need to talk about what do we need for the future,” said Freedman.