Jane Sun has a packed schedule. Arriving at her office in Shanghai near the busy Hongqiao airport early every morning, she has no time to see the planes come and go.

When not on one of those aircraft herself, she works long days, spending some of the evening with her family before getting back on work calls as the Nasdaq Stock Market rings its opening bell in the United States.

“I think I was very lucky because China opened its doors when I was growing up,” Sun, chief executive officer of travel service company Trip.com Group, told Nikkei Asia. “So I was among the first students to study abroad and when China took off I was able to return and build a good company.”

Four times, Sun was named by Fortune magazine as one of the world’s top 50 most powerful women in business. Trip.com’s market capitalisation has grown from around $1bn to $22bn since she joined the company.

She is one of hundreds of thousands of female executives and entrepreneurs buoyed by China’s economic liberalisation that began in the late 1970s and led to explosive growth over several decades.

The world’s most populous nation was once known for having the most advanced blueprint for women’s rights. One of the poorest countries in the world a few decades ago, it came to be hailed for its achievements in human development indicators, and gender equality surpassed many middle-income countries at the time.

China is now home to two-thirds of the world’s “self-made” women billionaires

But as decades of state-sponsored feminism led to women’s empowerment, and the communist state grew to accommodate capitalism, a decline in the birth rate has given rise to policies that are reinforcing gender mores, determining the kinds of jobs women take to prioritise care work at home, and pushing China in the opposite direction.

The gender gap has widened in recent decades, particularly in women’s employment, share of labour income and political empowerment.

“Chinese women had never been completely equal to men, and China did little to help improve women’s labour force participation in the past 30 years,” said Leta Hong Fincher, an adjunct assistant professor at Columbia University.

Still, home to 470mn females between the ages of 15 and 64, China has 78 “self-made” women billionaires. This is more than double the rest of the world combined, according to the Hurun Richest Self-Made Women in the World 2022. Neighbouring India, home to 450mn females in that age group, has three.

“Self-made” refers to those who did not inherit money from billionaire parents, according to Rupert Hoogewerf, chair and main researcher of the Hurun Report. The exclusive club, however, could include women who might have had access to parental assistance such as expensive private schools.

“Any entrepreneur, whether it’s male or female, could have benefited somewhere down the line from knowing somebody. It’s sometimes very difficult to determine whether they got advantage of a special government policy or a friend,” Hoogewerf said. This is particularly important in China, where the legal system is weakly enforced and relationships are crucial to doing business.

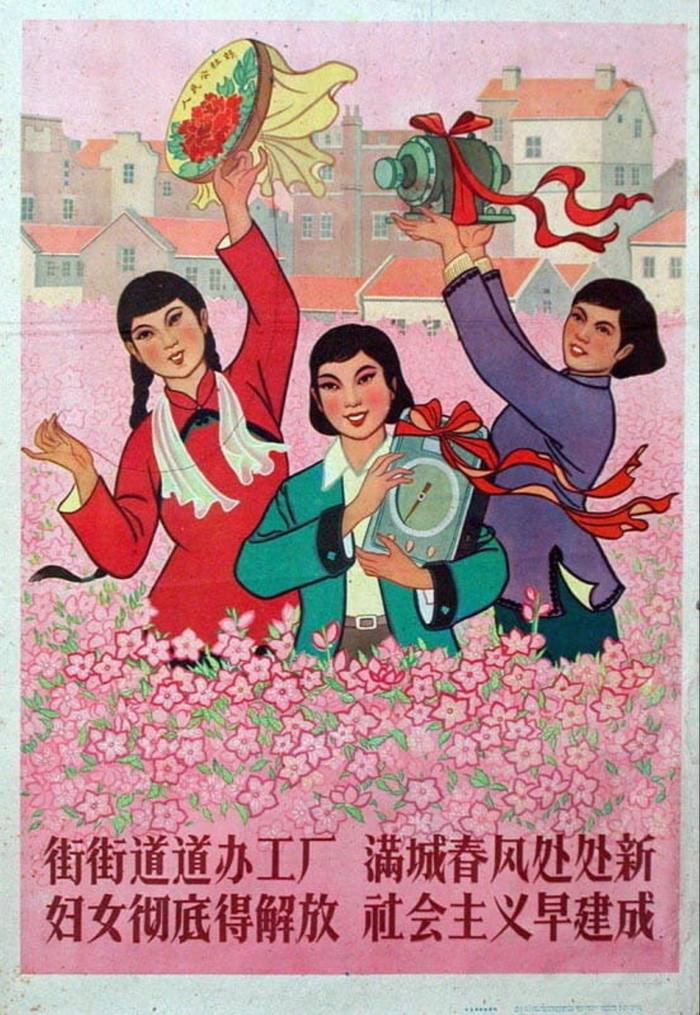

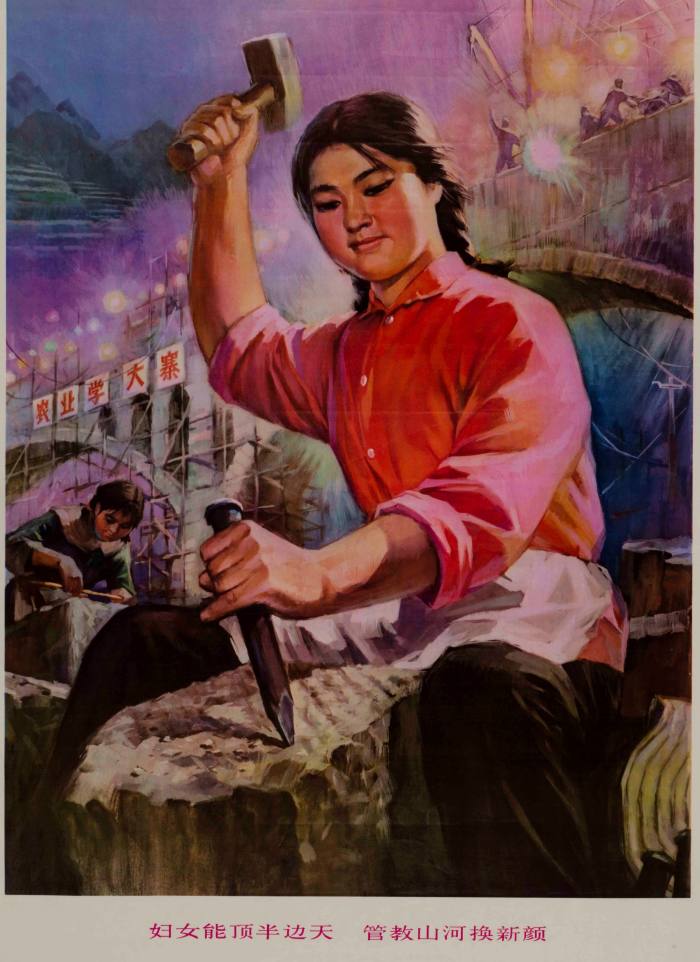

In the planned-economy era of Mao Zedong, the Chinese Communist party sought to provide women legal and social equality through the constitution, enacted in 1954. The government promoted the slogan “Women hold up half the sky” to illustrate the importance of women in China’s economic success.

“Women in China played a critical part in the communist revolution,” said Fincher. “With the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, the Communist Party required women to work to build a new communist nation. Female labour force participation was extraordinarily high and it remained so until early 1980s.”

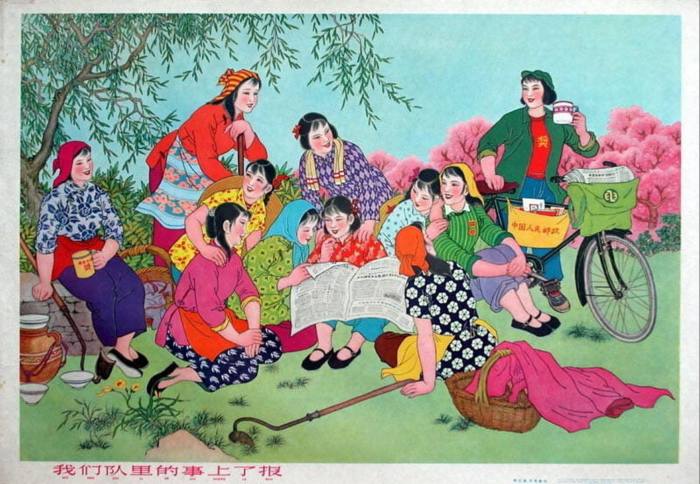

China had built massive day care centres within state-owned institutions and factories. These facilities were designed not to educate children, but to help with child care and facilitate the participation of women in the workforce, said Li Jun, Chau Hoi Shuen scholar in residence at the University of California, Berkeley.

“Under a party-led economy, the emphasis on gender equality and women’s liberation is partly related to the national agenda of economic development,” said Sisi Sung, Germany-based research fellow at the University of Erfurt.

This state-supported feminism promoted employment opportunities for women in the public sector and also provided benefits such as maternity leave. Expanded access to education, paired with cultural family support in which grandparents provided child care, also contributed to women’s wealth in China, said Liu Qian, managing director of Greater China for the Economist Group.

“China’s one-child policy has also helped women’s wealth, because most Chinese families prioritise boys’ education if they have numerous children, but send girls to school if they only have one,” Liu said, referring to the policy that was launched in 1980. Aimed at controlling the rate of population growth, it was a move that also hurt women as preference for sons led to millions of abortions and a “woman deficit”.

Women also benefited from China’s “college expansion policy” implemented in 1999 and aimed at quintupling college-going students. Girls in China typically perform better than boys in school, and the programme resulted in a higher ratio of females attending universities.

The proportion of women in college went from 38 per cent in 1998 to 50 per cent in 2009, and hovered at roughly 51 per cent in 2020, according to China’s Ministry of Education.

Driven by productivity gains and domestic demand, China’s GDP grew at a record clip from 1990 to 2012, averaging more than 9 per cent growth per year.

Armed with inexpensive labour and having joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, China steadily increased exports by assuming the role of the world’s factory.

This article is from Nikkei Asia, a global publication with a uniquely Asian perspective on politics, the economy, business and international affairs. Our own correspondents and outside commentators from around the world share their views on Asia, while our Asia300 section provides in-depth coverage of 300 of the biggest and fastest-growing listed companies from 11 economies outside Japan.

Subscribe | Group subscriptions

It also increased imports by gradually reducing tariffs. This led to massive gains in the country’s income levels, catapulting an agricultural backwater into the world’s second-largest economy in 2010.

“It’s not necessarily [a] women or men [issue], it’s really the wealth creation location,” said John Wong, a PwC partner who specialises in family and private client services.

In the last decade, women also rode the start-up wave as the cabinet called on ministries and local governments to support innovation. In the backdrop, fast-growing companies such as ecommerce giant Alibaba acted as drivers of job creation.

Hu Weiwei, co-founder of bike-sharing firm Mobike, was one of hundreds of young female entrepreneurs who rose to fame. She sold Mobike to food delivery giant Meituan for $2.7bn in 2018. Cindy Mi, co-founder of edtech unicorn VIPKID, was another to make the headlines.

With gross domestic product per capita surpassing $12,000, China is rapidly approaching the World Bank’s threshold to be considered a high-income country. But an attempt to balance the speed and quality of economic growth has slowed that pace in the last decade. Growth has slowed further with the country’s zero-Covid strategy and weakening global demand.

The IMF expects China’s economy to grow 3.2 per cent this year, while the World Bank expects 2.8 per cent, far below the country’s official target of 5.5 per cent, and less than a third of the rate a decade ago.

Inflation and economic slumps affect women more as they take pay cuts and lose jobs at a disproportionate rate.

The Global Gender Gap Index, which tracks progress towards gender equality, ranked China 102 out of 146 countries this year.

In 2006, when the World Economic Forum first published the report, China ranked 63 out of 115 countries. The index assesses the gender gap in economic participation and opportunity, education, health and political empowerment.

Until this year, China made little progress in bridging the gender gap in health, a sub-indicator based on sex ratio and life expectancy. Its position in women’s political empowerment has been slipping since 2010. For the first time in 25 years, China’s top political body, the 24-member politburo, does not have a single woman.

China is the only country this year with a gender gap of larger than 10 percentage points in secondary education enrolment in east Asia and the Pacific.

While countries such as Vietnam, Thailand, Singapore, Indonesia, India, Bangladesh and Pakistan have witnessed steady growth in women’s share of labour income, according to the World Inequality Database, China has seen a continuous decline since the 1990s, hitting 33.4 per cent in 2019.

And fewer women are making it to the top.

“Ironically, the explanation is the tremendous surge in economic growth in China,” said Liu from the Economist Group.

“It makes sense from a pure efficiency point of view for men to be more specialised in market work, and women in family work, since women tend to spend a longer time on child care and housework, and fundamentally pregnancy and part of the childcare cannot be biologically outsourced. However, this overlooks the fairness perspective. In other words, making more money doesn’t mean a more fair or even happier family or society.”

The movement on gender equality in China appears to be looping around to where it started. The party had advocated for equality since its inception in 1921. The first law that the People’s Republic of China introduced was the Marriage Law, which guaranteed women the freedom to marry and divorce.

But last year, China implemented a new law that stipulates couples seeking divorce must complete a month-long “cooling off” period to reconsider their decisions. This is a move designed to stem declining birth rates, which are tied to marriage rates in most Asian countries.

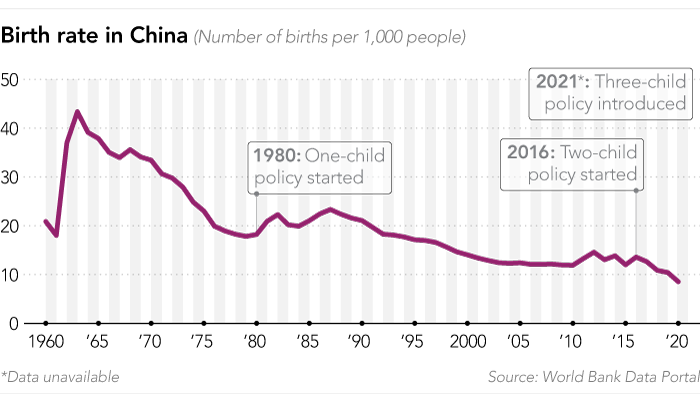

China’s census, released last year, showed that around 12mn babies were born in 2020 — a significant decrease from the 17.9mn in 2016 and the lowest number of births recorded since the 1960s. While the overall population grew, it moved at the slowest pace in decades, adding to worries that China might face a population decline sooner than expected.

In 2021, China’s birth rate fell for the fifth year in a row, to a record low of 7.52 per 1,000 people. Based on that number, demographers estimate the country’s total fertility rate — the number of children a person will bear over their lifetime — is down to about 1.15, well below the replacement rate of 2.1, and one of the lowest in the world.

China scrapped its decades-long one-child policy in 2016 to replace it with a two-child limit. As that has failed to reverse the declining birth rate, the authorities in 2021 said a married couple was now allowed to have up to three children.

As countries become more developed, birth rates tend to fall due to education and other priorities such as careers. Neighbours such as Japan and South Korea have also seen birth rates fall to record lows. What exacerbates it in China, though, is a gender imbalance.

There are 35mn more males than females in China.

China’s decades-long one-child policy and preference for male descendants — particularly in rural areas — led to forced abortions and a reported glut of newborn boys from the 1980s onward.

In November, China instructed women to uphold “family values” in an amended gender law, the latest sign of a strict return to traditional gender mores.

The now all-male politburo has admitted only six women since 1948; three of them were wives of Chinese Communist party leaders. Only three made vice-premier, and no woman has ever made it on to the elite seven-person Standing Committee.

Victor Shih, an associate professor specialising in Chinese politics at the University of California, San Diego, said the priorities for women’s rights would become “even more marginalised” without a woman sitting in the top political body.

“Even if being in the politburo does not necessarily mean they have decision-making power, the fact that women are no longer able to hold even a purely symbolic position indicates that the status of women in politics is deteriorating,” said Feng Yuan, co-founder of Beijing Equality, an NGO dedicated to women’s rights and gender equality.

As state-owned enterprises were required to cut businesses that were not essential to their operations, the more than 10,000 day care facilities China maintained in the early 1990s had nearly disappeared by 2010.

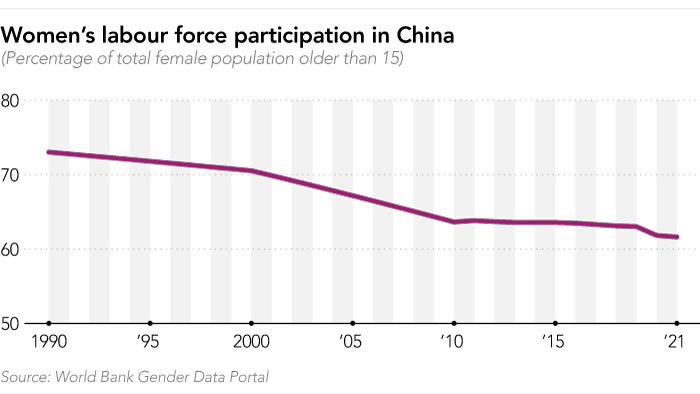

But as most other countries make their way towards parity, women’s labour force participation in China has been falling since 1990. It now stands at 61.6 per cent, down from 70.5 per cent in 2000, according to the World Bank.

With the onset of market reform in the 1980s, women were often the first to be fired during the restructuring of state-owned enterprises, and China hasn’t done anything to help improve women’s labour force participation at all in the past three decades, Fincher said.

“On the contrary, they’ve been aggressively pushing this propaganda on ‘leftover women’, which is aimed at discouraging educated women from working and being too ambitious,” said Fincher, who is also the author of the book Leftover Women: The Resurgence of Gender Inequality in China.

“Leftover women” is a term that refers to unmarried women in their late 20s and beyond, as defined by China’s Education Ministry

“This makes no economic sense, but it does make political sense. China has entered a new age, particularly under [president] Xi Jinping, in which political stability takes precedence above economic expansion. Marriage and family are seen as the ‘basic cell of society’ and represent a basic building block for social and political stability, so they are pushing more women into traditional roles of wife and mother at home.”

As of 2020, China had 2.5mn women above the age of 25 who had never been married, according to the China Population and Employment Statistics Yearbook.

The economic slowdown in China has undone a lot of progress, even for the nation’s richest women.

China’s wealthiest woman, Yang Huiyan, a majority shareholder in China’s biggest property developer, Country Garden, lost more than half her fortune amid the nation’s property crisis. Her net worth plunged to $10.8bn in the last year.

Wu Yajun, China’s second-richest woman and former chair of developer Longfor, saw her company’s stock price fall by close to 30 per cent since its peak in April 2021. Her net worth sank 23 per cent to $10.6bn.

Mi’s VIPKID fell victim to Xi’s sweeping crackdown on the edtech sector last year. The company, once valued at $4.5bn, had to shutter its core business and is now struggling to pivot.

China did not disclose its gender income disparity from 2010 to 2020 in its most recent survey on women’s social status. Experts believe this is because the gap has continued to widen.

“The wage disparity is also the outcome of occupational segregation by gender, which explains why there are disproportionately more men than women working in high-earning businesses like banking and more women working in moderate-earning areas like customer service,” said Feng from Beijing Equality. “Few women executives at large Chinese state-owned enterprises” also contributed to the gap, she said.

Although 55.9 per cent of working-age women have a bachelors degree or above (as against 33.6 per cent of men), only 34.2 per cent of women are in managerial positions, compared with 40.7 per cent of men, according to a report by Zhaopin, a Chinese recruitment services provider.

“When I talk to a lot of young modern women,” said Liu from the Economist Group, “I see that they in general don’t feel discriminated against, especially if they’re still in school, since they’re clever and perform well. However, this quickly changes after they start working, and is even more pronounced after marriage.”

Trip.com’s Sun, who was born to engineer parents in the late 1960s when China was a cash-strapped nation, has built her own path to success. Her parents made $15 each month, and she obtained a scholarship to attend the University of Florida. There, she worked as a waitress and a library assistant to pay for living costs.

Now in the top spot at her company, she argues that every organisation must have women at the executive and board levels and be mindful of benefits for female employees. Trip.com offers mid-level and senior female executives an allowance of $14,000 to $290,000 for egg retrieval and freezing.

It is illegal in China for unmarried women to freeze their eggs

Pocket Sun, founder of US-based venture capital SoGal Ventures, was born and raised in China and moved to the United States for higher education. There, she quickly realised the magnitude of gender disparity and co-founded SoGal to “change the status quo and disrupt the boys club”.

“It’s very, very common for women entrepreneurs to be asked about their marriage, their families, their kids,” said Sun, whose women-led firm invests in diverse founding teams in the US and Asia.

More women entrepreneurs are interested in freezing their eggs so they do not have to answer questions about fertility and timelines, Sun said.

Sun added that many female entrepreneurs now prefer to borrow money from relatives, or use their own savings, to avoid gender bias and hostility.

Sexual aggression towards women is also discouraging female entrepreneurs, Sun said, and is rarely discussed publicly due to political sensitivity.

In 2018, Liu Jingyao, a student at the University of Minnesota, alleged that the billionaire founder of one of China’s largest companies, JD.com, escorted her back to her apartment and raped her. Liu Qiangdong was arrested in the US and released within 24 hours. He insisted that the sex was consensual, and prosecutors declined to charge him.

On the Chinese internet, Liu was called a slut, a liar and a gold digger. The civil case she brought was settled in October. Last year, authorities in China also dropped a case against a former Alibaba employee who was accused of sexually assaulting a female colleague. “All of these things did not get any satisfactory results,” Sun said.

Given all of these challenges, young female entrepreneurs in China are likely to be those who come from affluence.

Chinese media also tend to focus on the family backgrounds of female entrepreneurs, which perpetuates the idea that a woman’s identity is tied to her family, Sung said.

“The bright spot is that you have a critical mass of young women in China who have recognised how bad the systemic sexism is,” Fincher said.

“If there’s going to be any improvement in the situation of Chinese women, it is going to come from young people on the ground, and when that pressure is strong enough it will force the government to change its policies a little bit.”

(This story is part of a series on women and wealth in Asia.)

A version of this article was first published by Nikkei Asia on December 20 2022. ©2022 Nikkei Inc. All rights reserved