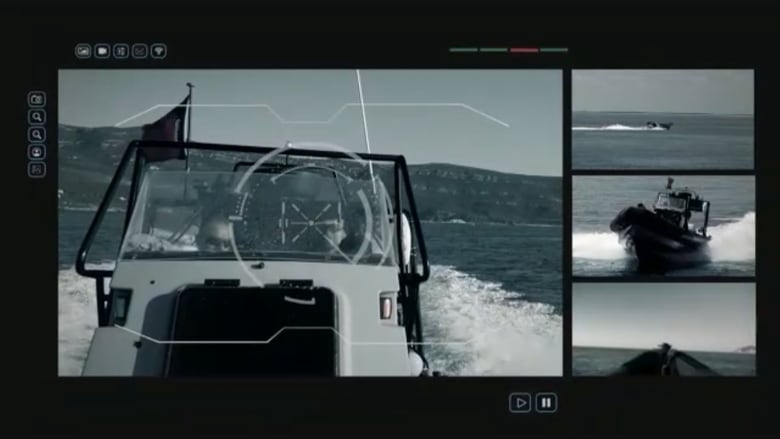

They can travel thousands of kilometres with no one on board, spend weeks at sea, and some are already armed with weapons.

Drone boats are in the water around the world right now, as both private companies and militaries experiment with the technology.

“We are at the very beginning of a robotics revolution, but at this moment in time we’re not going to win a war with robotics alone,” said Sean Trevethan, maritime capability manager at NATO headquarters in Brussels.

Also called unmanned or uncrewed surface vessels (USVs), these vessels are usually semi-autonomous with advanced sensors and computer systems that can be programmed to navigate vast distances and avoid obstacles at sea. For more complex work, they can be remotely controlled by a person thousands of kilometres away.

The range of applications for a USV is “quite broad,” said Trevethan. “You could end up with simply a missile barge, for example, or you could also end up with auxiliary ships that carry supplies…. The roles are almost only limited by our own imagination.”

The sensors on board some USVs can be used to seek out mines, detect submarines or even to help monitor the ocean’s environment.

Navies are interested in drone boats because they could solve several problems for them, including staff shortages. They could also go into dangerous situations without endangering human lives, or patrol large swaths of coastline.

‘It does dehumanize us’

There are also ethical considerations to grapple with. Automating military technology doesn’t sit well with groups like Mines Action Canada. It was founded in 1994 as part of a global movement against the use of landmines, and now runs a campaign to ban fully autonomous weapons.

Even though most drone boats are only semi-autonomous, Paul Hannon, the organization’s executive director, says more needs to be done to govern the remote operation of these vessels.

“I think it does dehumanize us to think that we are just a picture on a screen, or we are just a series of ones and zeros,” he said. “The distance makes it less personal. You’re in no danger, and that affects your decision.”

“I think there need to be some restrictions and prohibitions and regulations on a lot of this,” Hannon said. “Technology is way ahead of [the] military and politicians and diplomats at the moment.”

A number of NATO members are currently testing armed USVs. The British navy, for example, is in the final stages of trials for a rigid inflatable drone boat, according to Trevethan, which could be used to protect frigates and destroyers.

But the alliance had no drone boats in active service as of May 2022. And its rules of engagement prevent any kind of on-board weapons from being fired autonomously by a USV, said Trevethan. A person with their hands on the drone’s remote control would have to make the decision to fire, not the machine.

“Any weapon system the allies have will have a man on the loop by pure doctrine, law and ethics,” said Trevethan.

Improving efficiency

The Royal Canadian Navy is watching the development in USVs closely, and is working with “other organizations and militaries” to test small “remote surface vehicles,” said Cpt. Jeff Klassen, a public affairs officer with the navy, in an email.

It already uses five-metre-long drone boats called Hammerheads, which are piloted by remote control, as targets in weapons exercises. Gunners aboard large vessels such as frigates practice shooting and sinking them before they can reach the ship.

One of the main arguments for Canada to embrace drone boats is that they could help patrol the country’s massive coastline. Israel has already shown this is possible: It’s using them to patrol its territorial waters.

With a suite of video, radar and other electromagnetic sensors, drones can keep an eye on what’s happening in remote areas, said Bryan Clark, who researches naval warfare at the Hudson Institute, a national security think tank in Washington, D.C.

“Then your destroyers and frigates can focus on managing that operation and responding if something gets detected,” he said. “So it’s a much more efficient way to use the force.”

The U.S. navy is doing its own research on drone boats. And it has far bigger plans for the technology, along with surveillance work and mine hunting, they would like to see drone boats house missile launchers, said Clark.

The U.S. already has two fully autonomous ships called Sea Hunter and Seahawk, each of which is nearly 40 metres long.

While the U.S. navy did not return CBC’s requests for an interview, an official from the company that built the Sea Hunter and the Seahawk was happy to talk. The two vessels have travelled a total of 64,000 kilometres autonomously, said Nevin Carr, navy strategic account executive with Leidos, and a retired U.S. Navy rear admiral.

His company sees drone boats as a way to handle some of the dull, dirty, and dangerous work the navy tackles. That could include mapping the sea floor, going into toxic or radioactive environments, or combat zones.

Future potential

Carr said the drone ships are relatively inexpensive to build compared to other navy ships.

“Sea Hunter cost $25 million and that’s pretty cheap for a 130-foot ship,” he said, considering that destroyers can cost around $1 billion US.

Operational costs of drone ships are also lower, Carr said.

“The largest single cost in the navy right now is the money that goes to paying our people, paying them their paychecks but also their medical care,” he said, adding that the average destroyer has a crew of around 300 people, while an aircraft carrier has a crew of thousands.

Carr doesn’t believe drone ships will replace traditional vessels. Instead, they might feed information to crewed ships from areas they might not be able access, reducing the number of people needed on a mission.

Adm. Michael Gilday, chief of U.S. naval operations, has said he hopes that drone boats will be an important part of the fleet by the 2030s, according to Carr.

But before navies fully embrace drone ships, at least one more technological hurdle needs to be overcome. Navy ships need a lot of power to move them around, and they run almost exclusively on big diesel engines.

“There are no diesel engines that are designed to run for three months right now, without human intervention. Everything is designed to have a mechanic that takes care of something, or changes the oil, or oversees the system to make sure it’s not overheating,” said Carr. “So you have to adapt many of those systems so they can truly be autonomous.”