When Vesuvius, the volcano on the Bay of Naples, Italy, erupted in 79 AD, it sent out a cascade of popcorn-like pumice, followed by ash, burying the city of Pompeii to its south.

But Herculaneum, a seaside resort town that had been frequented by senators and other wealthy Romans, was actually closer to the volcano.

After the initial explosion, Vesuvius imploded, releasing a massive flow of hot mud that ripped off rooftops and carried benches, beds and tables down to the shore, encasing the objects — and, amazingly, preserving even those made of wood.

Now, for the first time ever, a comprehensive exhibit of those astonishingly rare wooden remnants from ancient times opens in Reggia di Portici, an 18th-century palace just down the road from Herculaneum.

Objects on display include everything from decorative door and ceiling frames to a wooden change purse, woodworking tools and tables, bed frames, boats and benches, even a small dresser whose doors still open.

Perhaps most extraordinary among the objects is a child’s crib made of oak — now carbonized — which, with a gentle push, still rocks. It’s a find Domenico Camardo, an archeologist with the Herculaneum Conservation Project, says moves him every time he catches sight of it.

“Inside the crib, we found a little mattress with the skeleton of a baby. And nearby, in the same room, the skeletons of four adults,” he said. “They were probably hoping to seek refuge there.”

Sealed under pyroclastic covering

While the Archaeological Park of Herculaneum has an on-site exhibit of jewelry and decorative objects made of gold discovered here, park director Francesco Sirano calls wood an especially intimate material, one that provides glimpses into the everyday lives of people.

“Marble and stone give you a sense of the monumental aspect of towns … but with wood, it’s not just the object, it’s what people did with and around the object,” he said. “And seeing these wooden objects, you see how little has changed in how we live.”

The wooden objects survived in part because the town was sealed off under a 20-metre-thick pyroclastic covering — making it next to impossible for grave robbers to access, after it was discovered by well diggers in 1709. For years, Herculaneum’s bounty was largely ignored, as archeologists focused on the larger and easier-to-access Pompeii.

While the two towns were both buried in the same eruption, they provide fascinating contrasts.

“The mud that covered Herculaneum travelled at a terrifying speed and was so hot that when it came into contact with people, they instantly evaporated — all but their bones,” said Mario Notomista, another archeologist with the Herculaneum Conservation Project. “They died so fast they didn’t even know it.”

In Pompeii, the ash that covered the city encased the bodies of trapped inhabitants, which decomposed, leaving empty molds of people caught in desperate embraces or curled in fetal positions. In Herculaneum, it’s skeletons that remain two millennia later.

“The bones all have traces of red, remnants of iron in the blood of the people who evaporated,” said Notomista.

The wood remains ‘alive’

The mud that enveloped Herculaneum was airtight, sealing off oxygen from everything it covered, preventing combustion, and thus preserving the wood and other organic objects, including charred food — an extreme rarity in ancient buried sites.

A stroll along the ancient roads and elevated stone sidewalks takes visitors past wooden doors, window frames, trellised gates, beams and even remains of vegetables in a deep clay pot where street food was prepared and served.

The food and most of the wood is carbonized, black and coal-like. But some, like the door in a thermal bath dividing a cold room from a hot steam bath, looks like it could be a few hundred — rather than two thousand — years old.

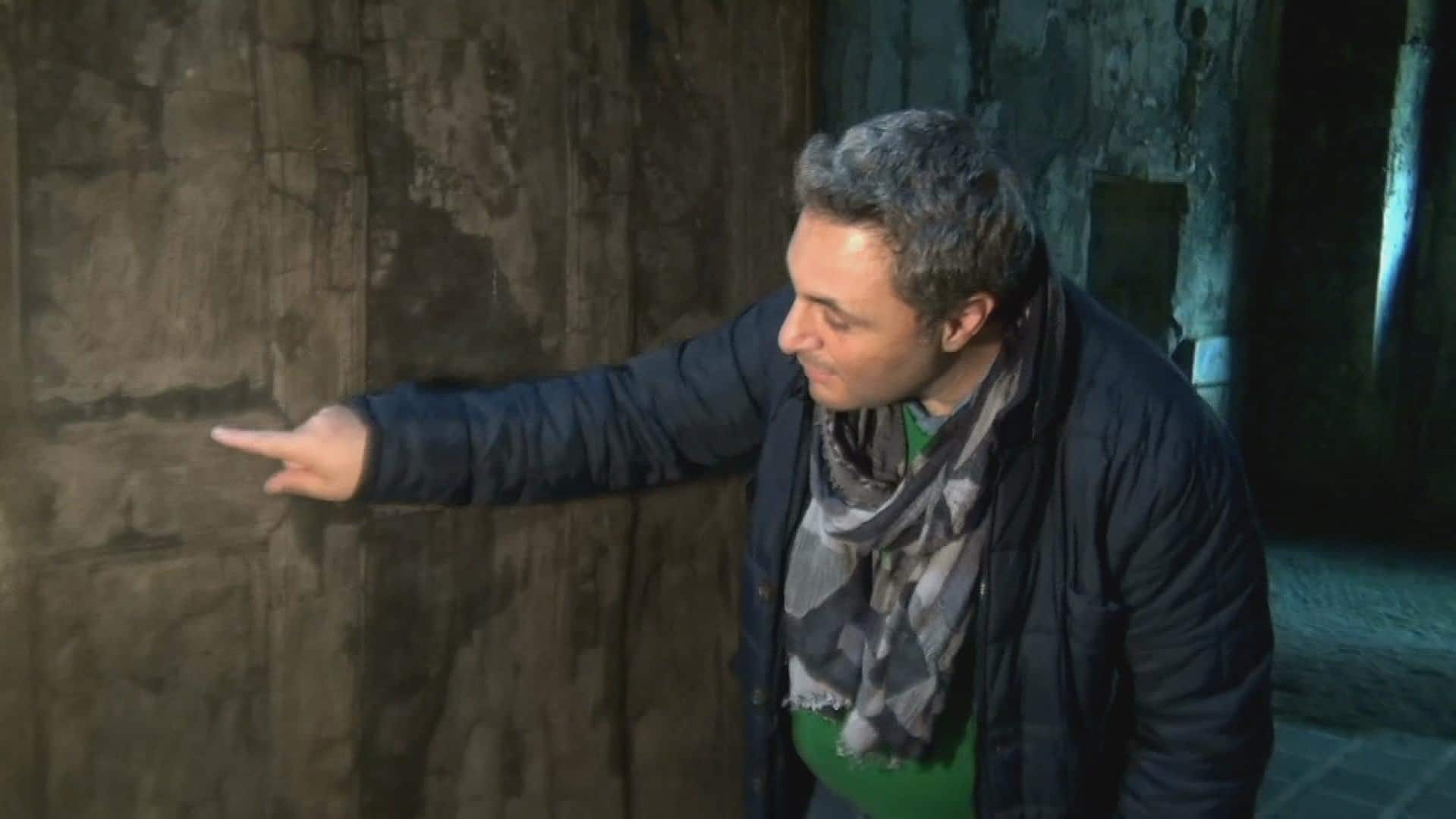

“Because of the humidity in this room, the wood remains ‘alive.’ That allows you to see amazing detail — the cornices and even the wooden nails,” said Notomista, pointing through the plexiglass protecting the door at the small, circular head of the nail.

WATCH | Mario Notomista explains how wood door was so well preserved:

Archeologist Mario Notomista points out the detail preserved in a door separating a cold room from a steam bath.

Many of the objects on display — tables, dressers and bed frames — were found trapped in rooms.

They include meticulously carved ivory reliefs depicting small offerings to the gods and tree deities, which decorated the legs of tables and three-legged pot holders made of ash wood, as well as the wooden feet and parts of the tables.

The furniture was discovered alongside marble statues in a room overlooking the sea in the luxurious Villa of the Papyri, named after its library of 1,800 papyri, or scrolls, located on the outskirts of town. Scholars believe the villa belonged to Senator Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, the father of Julius Caesar’s first wife.

Preservation of the wood poses endless challenges — not just in protecting the exposed carbonized beams attached to buildings against degradation, but in reconstituting the internal tissue of non-carbonized wooden objects, like the claw-shaped foot of a table, which was weakened by the moisture it was trapped in.

The challenges of preservation

For the first time in Italy, restorers used a new method involving a weeks-long process of bathing the objects in an increasingly concentrated solution of hydrogenated sugars, which the wood absorbed, and then slowly drying them to allow the sugar to crystallize inside the objects and reinforce them.

A decorated wooden beam with traces of gold leaves and Egyptian blue and other colours of paint still clinging to it — uncovered during a dig a decade ago on the ancient beach — was preserved using the same method.

“In Egyptian times, this blue was extremely precious, but we realize that in ancient Rome, even if it was expensive, it was much more common, because it was painted on the ceilings,” said Elisabetta Canna, a restoration expert at Herculaneum.

“It’s incredible these pieces have survived 2,000 years of being buried, moist from the sea … and are now seeing the light of day.”

The beam is one of 250 such fragments that also provide proof Romans in the first century AD were already using the triangular wooden structure known as a roof truss in construction.

The restoration and maintenance of Herculaneum stems from a public-private partnership with the California-based Packard Humanities Institute, which provides training and expertise.

Herculaneum director Sirano says he hopes the exhibit will help bring more to life people’s imaginings of the past, and inspire designers to borrow details from the ancient world for the future.