More than 25 years ago, Frozan Rahmani was an inquisitive, precocious teenage girl living in Kabul. She recalls listening to the radio every day after the first Taliban takeover — waiting in vain for the announcement that her school would reopen.

It took more than five years — and the violent overthrow of that brutal, hardline Islamist regime — to realize her dream of returning to class.

Now, the Taliban are back in power in Kabul. From the safety of Canada, Rahmani has watched friends and family swept up in the unraveling of women’s rights in Afghanistan — a flashback to her own personal nightmare.

“I feel their pain,” Rahmani told CBC News.

Rahmani is an Afghan journalist who was forced to flee the western-backed government in Kabul after investigating corruption allegations. She said she could not sit idle after the Taliban victory last summer and watch the slow eradication of the social progress women had made in their absence.

Using her own money, time and contacts, she began remotely documenting the disintegration of women’s rights under the Taliban.

Her work has been turned into a 16-minute documentary — a sometimes grainy visual record that is both deeply personal and profound, according to several Canadian officials, including a former ambassador.

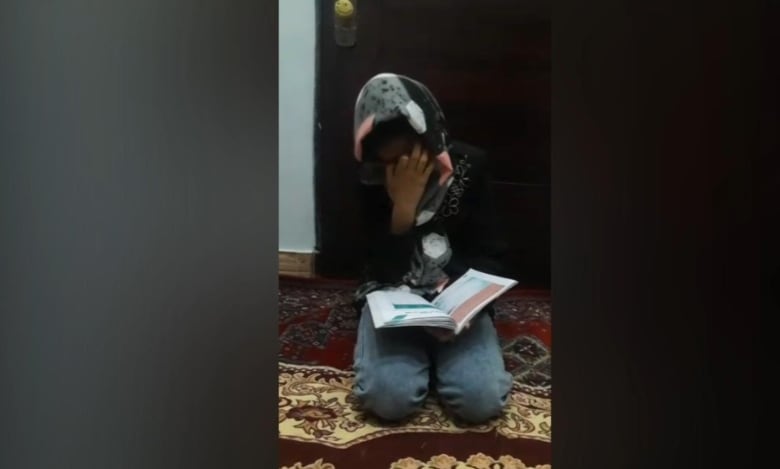

One of the stories she has documented belongs to a young woman named Farhat, who was in Grade 7 last summer when hardline Islamists regained power in Afghanistan.

“Now she’s banned from going to school,” said Rahmani. “I remember the same situation I was in 25 years ago.”

Her advice to Farhat, she said, is to cling to her dream of an education through “all those tears and sorrow.”

“When I was banned from going to school, in that time, I was not silenced as a teenage girl,” said Frozen, who arrived in Canada in 2016 not knowing a word of English.

“I try to learn … by reading my brother’s books. I improved my reading, writing and … I try to learn.”

It’s that never-surrender spirit she brings to the documentary, which has yet to be translated into English.

From here she can only watch the daily struggles of Afghan women, the protests they stage briefly before the authorities shut them down — sometimes violently. The war in Ukraine may be consuming the world’s attention but Rahmani is determined to wake up the West to what’s happening in her former home.

‘Afghan women are very strong’

“It motivated me to be not silent to raise [and] raise awareness,” she said. “I totally found myself [in] those interviews I just collected recently.”

She said her interview subjects fully understand they’re risking their lives merely by appearing in her documentary.

“It’s risky for them, but I spoke with them and I told them at will, we will publish these videos and they said it’s okay,” she said.

“But as we know, Afghan women are very strong.

“They are standing to fight about their education and their rights and freedom. I think there is no fear for them. We know this is risky, but they want to raise their voices.”

Shortly after taking over, the Taliban promised more than once to continue to respect the place women had carved out for themselves in society. Nipa Banerjee, Canada’s former head of development aid in Afghanistan, said each of those pledges has been slowly walked back.

“I did not expect a miracle to happen and the Taliban to, you know, sort of cooperate with the Western world, in terms of humanitarian rights,” she said.

Banerjee is an advocate of countries engaging directly with the Islamist regime. Documentaries like Rahmani’s, she said, offer a reminder of why it’s dangerous to leave the Taliban to their own devices.

“It is very important that this kind of work is done because we will not know what’s going on otherwise [in Afghanistan],” she said.

“I would say this is one of the reasons why we should keep talking to the Taliban, keep engaged with the Taliban, so that we know what is going on. If they are completely isolated, we abandon them, along with the people of Afghanistan, the very poor, ordinary Afghans.”

Isolate or engage?

No country has yet recognized the Taliban regime as the legitimate government of Afghanistan. There’s a heated debate going on in the international diplomatic community about whether recognition of the Taliban government could come with conditions attached, such as respect for human rights.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau recently said Canada has no intention of recognizing the Taliban regime.

He was responding to a CBC News story earlier this month that revealed Canadian officials have met with Taliban representatives on at least 13 occasions since the fall of Kabul in August of last year.

The documents, obtained through access to information law, show David Sproule, Canada’s senior official for Afghanistan, has pressed the Taliban for commitments on permitting women to seek education, fighting terrorism and granting safe passage to Afghans who want to leave the country.

Unlike its allies, Canada has refused to carve out a legal exemption to anti-terrorism laws which would allow aid groups to deliver humanitarian assistance directly to the country.

Canada has opened its doors to up to 40,000 Afghan refugees — but experts such as Banerjee say that does little for the people trapped under the regime.

One Afghanistan expert says Rahmani’s documentation of women’s experiences under Taliban rule could help to break down the federal government’s apparent indifference.

William Crosbie is a former Canadian ambassador to Afghanistan, now executive director of an Afghan-based non-governmental organization known as the Heart of Asia Society. He said some members of his organization were in Kabul recently, meeting with Taliban ministers.

Education for girls and children in general was a top priority for the Canadian government when Crosbie served as ambassador. The Conservative government of the day had laid out a five-year plan to assist Afghanistan’s efforts to educate its kids.

‘No hope for the future’

“It’s been really sad, and in fact devastating, to see the impact that the Taliban regime has had on all of those priorities for Canada, and particularly, for all those women and men who have been educated over the past 20 years, and have started careers and lives that have now been abruptly ended,” Crosbie said.

Since the Taliban takeover, he added, “western countries for the most part have said, ‘We’ve tried, we’ve had no hope, no effect.’

“So basically, we’re just going to send humanitarian assistance … That leaves the Afghan people, frankly, with a level of basic nutrition but no hope for the future.”

While it’s important to engage with “those in power,” Crosbie said, his NGO has focused on creating “a national dialogue that may — or may not — include the Taliban” by trying to help young people and local community leaders.

Where Rahmani’s work could be particularly important, he said, is in the effort to wake up audiences in the region and the West to the worsening plight of Afghan women and girls.

“What’s important, with documentaries such as hers, is to have them translated into other languages, get them translated into Persian,” said Crosbie.

“We need to ensure that the countries surrounding Afghanistan, Pakistan or Iran, India … are hearing these voices from within Afghanistan, because they’re the ones who need to persuade the Taliban that they have to move towards an inclusive regime.”