Two and half years ago, as an unknown virus swept the nation, I found hope in an unlikely place: the NHS. Hospital doctors and nurses were gripped by a spirit of camaraderie and can-do, in stark contrast to the weary burnout we see today. As the NHS approaches its high noon, with the cataclysmic combination of nurses on strike for the first time in a century and ambulance workers to walk out next week, I remember that glimpse of a way to do things better.

I had a strange and privileged experience in 2020, as a temporary adviser to the Department of Health. Sitting in the dysfunctional centre of government, which had a vacuum where a prime minister should have been, I briefly witnessed a fragmented system come together to do what frontline staff thought was right for patients, liberated from some of the usual protocols.

When Covid hit, dental hygienists, surgeons and physiotherapists retrained as ICU nurses. Care workers gave insulin injections and wrote death certificates. Even the BMA, that bastion of conservatism, had to drop its attempt to stop medical students looking after Covid patients. At one Zoom conference I attended, organised by a surgeon, hundreds of GPs and consultants said passionately that they no longer wanted to work in silos; that they were collaborating in new ways; that they had been liberated from HR jargon and form-filling.

“We must never go back” was their refrain in the spring of 2020. But we have. In less than a year, the bureaucracy reasserted itself. Retired doctors who volunteered to help with the vaccine rollout were required to undertake 18 training modules, including one on preventing terrorism.

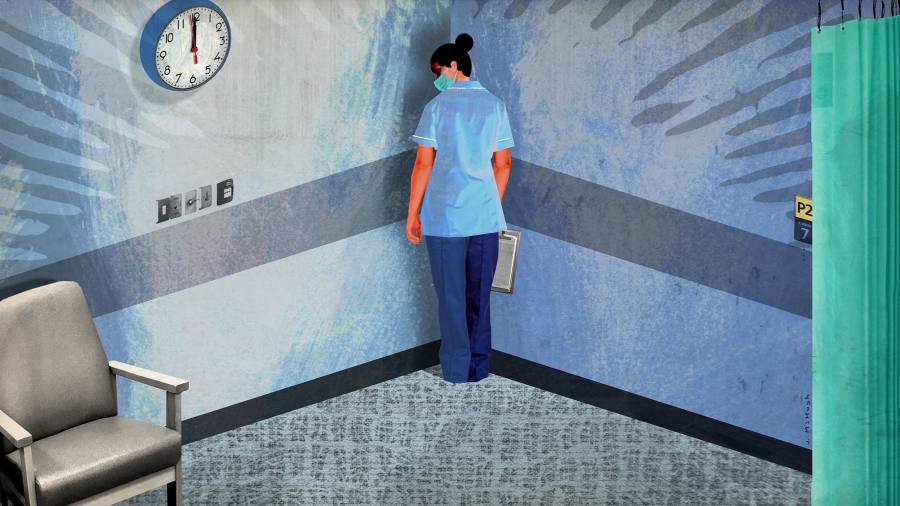

Mind-numbing “guidance” gushes from the centre as strongly as ever. Nurses tell me of money being spent on “comms” teams rather than healthcare. Surgeons tell me they are doing fewer operations than pre-pandemic because of infection control measures, failing computer systems and theatre staff turning up late. Last year, 12,600 operations were cancelled because of administrative errors. When professionals are exhausted, facing a backlog of 7mn patients, and pay is falling in real terms, it is hardly surprising that so many are leaving, or on strike.

Where has all the extra money gone? A new report from the Institute for Fiscal Studies finds that the NHS is treating substantially fewer patients than it was before the pandemic, despite having more staff and more money (its current budget is £180bn). The usual explanation for poor performance is that demand is outpacing funding. But the IFS suggests that the money is being spent on the wrong things.

The past three years have seen large increases in the employment of consultants, junior doctors, nurses and clinical support staff. There were 10 per cent more consultants, nurses and health visitors in July 2022 than in July 2019. This doesn’t seem to be translating into higher productivity, partly because some patients are sicker and require more treatment, and partly because beds are being “blocked” by elderly people who are fit to discharge but unable to access social care.

Yet the analysis also suggests that many of the new hires are at senior or junior ranks, not in the middle. We risk losing the backbone of the NHS: the registered nurses who manage the day-to-day delivery of care. There are more specialists and fewer generalist GPs and community nurses who can help patients at an earlier stage.

Even with all these extra staff, there are still so many vacancies. Why? One NHS insider explained to me that when funding rises, so does the number of funded posts. So boosting resources automatically creates a workforce shortage. I have been shown that the number of “establishment” posts (required staffing levels) jumped up when new funding was announced. This is insane.

For decades, debate about staff numbers has been the currency of politics. Successive governments have paraded “more nurses, more doctors” as a cure-all for warding off criticism. But when the NHS has 200,000 more staff than it did in 2012, and 1.2mn staff overall, it is time to ask about how staff are being used, not just how many they are. “Staff undoubtedly feel stretched” write the IFS authors. “But it is not obvious that adding more staff or money would immediately unclog the system”.

There is an opportunity here to change the conversation. Wes Streeting, the Labour shadow health secretary, seems refreshingly ready to do just that. “I’m not afraid to take on vested interests,” he said recently — including in his own party.

If the NHS and its frontline are to do their best for patients, we need a revolution in organisational management. General Sir Gordon Messenger, former deputy chief of the defence staff, recently reviewed the state of NHS leadership and concluded that there has been “institutional inadequacy” in the way managers are “trained, developed and valued”. Even if overhaul is tiring, change is now vital, to restore autonomy, respect and proper support.

Covid posed an immediate threat which spurred NHS professionals to rise to the challenge of their vocation. This crisis feels very different: a desperate grind to get through each day, where everything is urgent.

Nigel Edwards, CEO of the Nuffield Trust, used to joke that in the NHS: “next week is strategic; the week after is the unimaginable future”. It’s no longer a joke. Unless leaders can show there is a better future, no amount of new staff will fix the problem.