NHS staff are some of the most brilliant, selfless, heroic people on this planet. They work under unimaginable pressure to achieve miracles, and are often paid far too little for their efforts. It is absolutely right that the government continues to increase funding and the workforce, especially as we live with an increasingly ageing and ailing population.

But hiring more frontline medical staff and increasing the NHS’s budget for day-to-day spending is not going to alleviate the current crisis in emergency care, or bring about a sudden reversal in the ballooning waiting list. That is because these crises are not caused by a staff shortage, they’re caused by a bed shortage.

If you put another fully equipped ambulance out on the road, you’ll be able to get out to one extra person, but if you haven’t freed up an extra bed, the patient is just going to have to join a now even longer queue outside A&E.

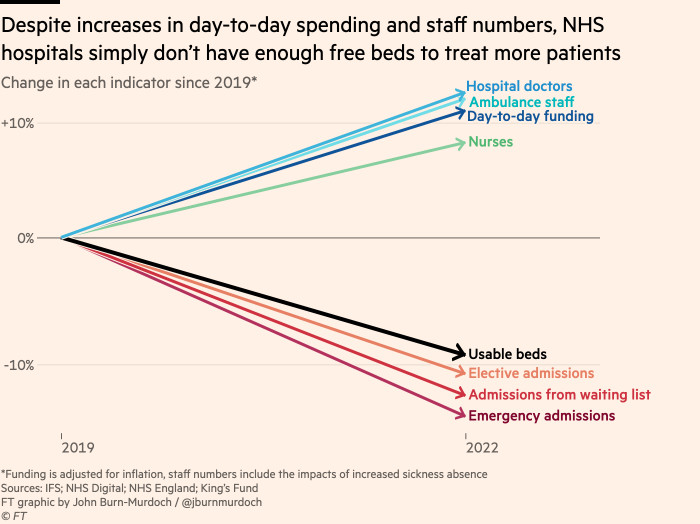

Don’t just take my word for it. Compared with the eve of the pandemic, the NHS is now spending 11 per cent more on day-to-day activities in real terms. And despite record numbers of voluntary resignations, the NHS has 12 per cent more hospital doctors and ambulance staff and 8 per cent more nurses. Yet today it is treating 12 per cent fewer patients from the waiting list than it was in 2019 and admitting 14 per cent fewer emergency patients. Virtually every measure of activity is down (though new cancer appointments are a heartening exception).

These are the striking findings of a study by Max Warner and Ben Zaranko at the Institute for Fiscal Studies, which underscores the extent to which this crisis is a beds crisis — and an infrastructure crisis more broadly — rather than a staffing and day-to-day resource crisis.

By my calculations, the only indicator of NHS capacity that has tightened over the same time period is the number of beds available for new non-Covid patients.

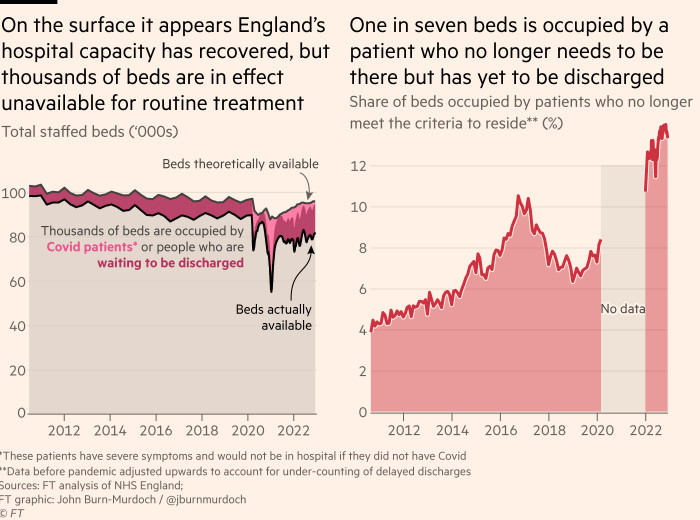

Nominally, there are almost exactly the same number of staffed beds in English hospitals today as there were in December 2019. But this is not true in any practical sense. Almost three years into the pandemic there are still about 2,000 hospital beds in use by patients with severe Covid who would otherwise not be there. And far more significantly, there are almost 14,000 beds occupied by patients who no longer need to be in hospital. More than double the total spare capacity currently available for admitting emergency patients are just sitting idle.

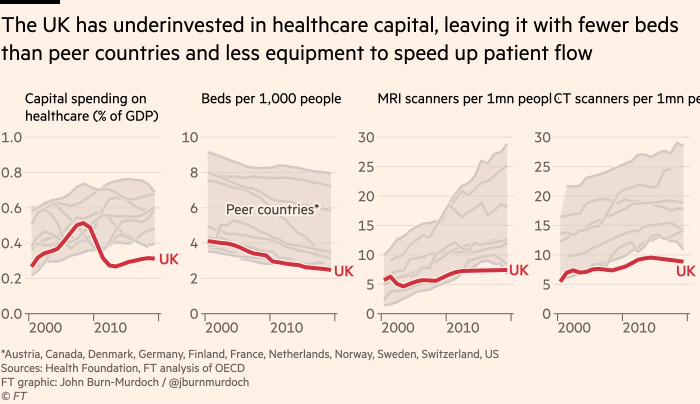

And why are we not seeing this near collapse in country after country? Because the British government has underinvested in infrastructure for the best part of two decades. The UK’s overall health spending is not dissimilar to peer countries, but its capital investment is anaemic. Going into the pandemic, Britain had fewer beds per head than virtually any other developed country. One of the few country’s running a similar lean operation — Canada — has also suffered the ignominy of a midsummer ambulance crisis.

Without the ability to conjure thousands of beds out of thin air, solving the delayed discharge problem — and reducing the amount of time people need to spend in hospital more broadly — is the single thing that will rescue the NHS from this perma-winter.

The instinct here is to lay the blame solely on the underfunding of social care, but there are far lower-hanging fruit. Record-keeping systems are so outdated that many English hospitals do not know how many intensive care beds they have, making the planning of efficient transfer of patients in and out of beds a non-starter — and the NHS already has case studies to point to for digital transitions speeding up patient flow.

I don’t expect us to clap for software platforms anytime soon, but if we as a country care about empowering our frontline medics to do what they do best, and relieving the unbearable stresses brought about in no small part by having to operate with antiquated infrastructure, then we need to move the conversation beyond “more cash and more doctors”.