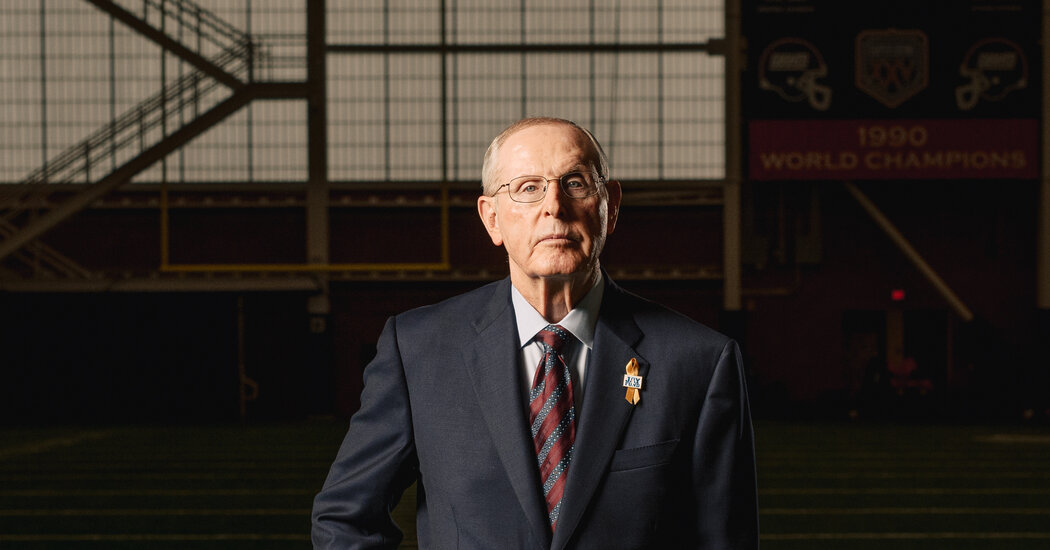

Tom Coughlin was an unforgettable sideline presence in the N.F.L. for parts of three decades, a driven, tightly wound field general whose style matched the game’s inherent intensity.

But as a young man, Coughlin almost quit coaching to peddle annuities to everyday folks. Married with three children, Coughlin, then 33, was attracted to a stable desk job after he lost an assistant coach’s position at his alma mater, Syracuse University.

Judy Coughlin, who had known her sports-loving, competition-obsessed husband since high school, listened but ignored his new career plans. With a smile, she said: “Sure, you’re going to sell insurance.”

Judy, 77, died last month from progressive supranuclear palsy, an incurable brain disorder that erodes the ability to walk, speak, think and control body movements. Coughlin, who led the Giants to two Super Bowl victories before leaving his last coaching job in 2015, spent the last several years as his wife’s primary, full-time caregiver.

During that time, Coughlin, now 76, was moved to write a contemplative memoir of his career titled, “A Giant Win.” The book’s framework is a detailed examination of the Giants’ stunning Super Bowl upset of the undefeated New England Patriots to end the 2007 season, but a subplot is Coughlin’s assessment of a life of triumphs, personal lapses and lessons learned.

In a video conference interview, Coughlin, who ranks tied for 14th in career N.F.L. coaching victories, talked about his candidacy for the Pro Football Hall of Fame, whether he has successfully softened an authoritarian image and his ardent support for more institutional assistance for caretakers of seriously ill family members.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and condensed.

You spend large portions of the book reflecting on your upbringing in a small upstate New York town and revisiting various pivotal life decisions. You’ve never been publicly introspective, why now?

Well, I’ve been out of the game for a while, and honestly what we were going through with my wife, it makes you think about everything. Some days I would be so exhausted that all I did if I had a break was take a nap. But other times, maybe two or three times a week, I would take an hour here or there and I’d sit and spend that time on the book. You begin to think and look at everything over and over again. I don’t know if that’s what reflection means, but that’s what I did.

One of the recurring messages of the book is that a coach has not succeeded unless he or she is a good teacher. You were well known for your rules — like setting the locker room clocks five minutes ahead to mandate being early — but you don’t see that as defining your legacy.

Look, everyone seems to know I did things differently. But I was also a big life lesson guy with my teams. Every week before a game, I always included some things of value and virtue that I thought were important that had nothing to do with football exactly. It might be something happening halfway around the world, but I had the inspiration to discuss that with my team. When all is said and done, I hope that I made an impression on those guys with those life lessons as well.

Can stories like that alter your public image as a strict disciplinarian?

I’m not sure. I do know that players like Michael Strahan and Eli Manning and others have been very good ambassadors on my behalf when questions about me come up. And I appreciate that.

Why is the first Giants Super Bowl victory over the undefeated Patriots especially meaningful to you now?

It’s the best Super Bowl game ever and certainly the greatest upset of all time. And with what this nation is going through with Covid and maybe a recession there’s a lot of people right now who are down on their luck. Maybe our story — a coach that everybody was trying to fire and a quarterback that nobody was sure of — can help them get up off the floor and make something happen.

Summarizing the Giants game plan that day you wrote: “We were going to knock Tom Brady on his ass.”

We knocked him down on their first play from scrimmage and 16 more times, including five sacks. It’s why we won that game.

You’re one of eight coaches to win two or more Super Bowls and not lose one. Have you thought about being inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame?

Yeah, I can dream like anybody else. That’s the pinnacle of your profession. People talk to me about that from time to time. But it’s something I don’t have any control over.

Your experience with your wife’s disease has made you a vocal advocate for others in a similar experience.

There are 50 million Americans who are just like me. I could afford to have some caregiver help, because frankly it could take two of us to do what we had to do. But there are so many families that don’t have that option; it’s often left to one individual. I think that should be recognized and hopefully for those who don’t have the means, there could be some way to give them some extra assistance. Because it’s a tough, tough job.

As a coach you were renowned for only taking five or 10 days a year off. But near the end of your book you concede that you wished you could have slowed down occasionally and enjoyed things more.

Yeah, I think my wife would have liked that more, too. But you know, I just kept moving forward to the next thing. To celebrate our Super Bowl win we had a parade down the Canyon of Heroes and then a reception with 35,000 people at Giants Stadium. It’s a remarkable experience. But what did I do next that day? Months earlier, I had scheduled a dentist appointment that afternoon. So I went to the dentist. You know, life goes on. I got my teeth cleaned.