Imagine hearing about the Holocaust for the first time from a survivor of its atrocities — the pain on their face starkly visible in the holographic image projecting just feet away.

Soon, youth in Toronto can immerse themselves in these experiences, part of a movement toward using education to eliminate a rising tide of antisemitism.

By reaching kids when they’re young, educators hope that these stories will be the way that future generations learn about the painful parts of history — and the ways in which they’re surfacing now.

Dara Solomon is among those leading the charge.

“I felt that I did not grow up with much antisemitism in Toronto in the late ’70s and ’80s,” said Solomon, the executive director of the Sarah and Chaim Neuberger Holocaust Education Centre in Toronto. “My children are growing up in an environment where we do have to talk about these things. And, you know, it’s really unfortunate — it’s very unfortunate — that it has been normalized by popular figures in the media.”

An increase in violence

The world has seen an uptick in antisemitic events this year; in Canada, B’nai Brith has documented a 733 per cent increase in violent incidents against Jews, resulting in an average of eight reported cases every day.

Those figures are amplified by hateful comments made online, including those made recently by rapper Kanye West, pushing leaders in the community to call for better education and awareness about the hatred and discrimination targeting Jews.

Solomon hopes the new Holocaust Museum set to open this spring in Toronto can be part of the solution.

The museum is geared toward school-aged children and will use a variety of archival videos and artificial intelligence to immerse kids in the experience, which includes survivor testimonies that are told using lifelike 3D holograms.

Solomon said surveys have found that many Canadians have limited understanding of what happened during the Holocaust. The Azrieli Foundation, a non-profit that does work in Holocaust education, in partnership with the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, commissioned a national study testing Canadians’ Holocaust knowledge in 2018. What it found was that 22 per cent of people between 18 and 34 hadn’t heard of the genocide — and more than half of survey respondents didn’t know the extent of what happened or how many Jews were killed.

So education can be a powerful tool to counter prejudice, said Solomon who is heading the new museum.

“From different studies and data, we know that Holocaust education — the more people know about the Holocaust and these sort of extreme dangers of hate — the less likely they are to be inclined towards, like, neo-Nazi beliefs and other forms of hate,” Solomon said.

To achieve maximum historical accuracy at the museum, Solomon’s team worked closely with survivors, among them Pinchas Gutter, who has devoted much of his post-war life to sharing his experiences and educating future generations.

Gutter said doesn’t see his work as a Holocaust educator as a choice.

“It’s my duty to try and bring about a tiny drop of improvement in the way the world is working, even if it’s just a tiny one,” Gutter said. “My credo is you have to try and, therefore, it’s so important for me. It is my duty and my solemn promise.”

‘Listen to witnesses’

Gutter speaks to thousands of people every year about the horrors he experienced during the Second World War, including his time as a prisoner in a concentration camp and on a death march. He lost most of his family in the Holocaust, and he says couldn’t talk about the experience until therapy helped him cope enough to speak of it years later.

He said he is especially excited about the opening of the new Holocaust museum because of how many people it will reach.

“Thousands of children and teachers and others are going to be educated there,” Gutter said of the museum. “It is terribly important for somebody like me to go out and tell people to listen to the truth, listen to what actually happened, listen to witnesses.”

Education centre on wheels

The Friends of Simon Wiesenthal Center for Holocaust Studies has also expanded its educational programming in response to rising reports of hate. The group built a mobile classroom in a bus in 2013, called The Tour for Humanity, and regularly visits small communities in and around Toronto to educate children about the Holocaust, all the while teaching them how to be advocates in their own communities.

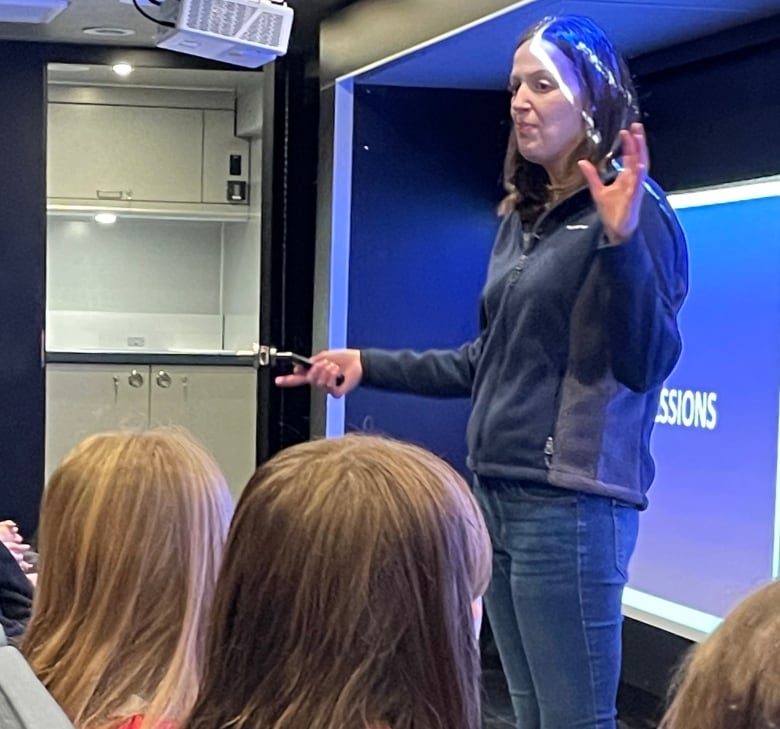

One of its lead educators, Daniella Lurion, says the work she does is critical — especially now.

“Marginalized groups are being targeted all over the place, and I think it’s a little bit scary,” Lurion said. “That’s why it’s important [to work] with schools, because we get kids at a younger age.”

The bus has taught 150,000 students in 750 schools across Canada since its inception, and Lurion says it’s busier now than ever. She says that going to smaller communities, where Jewish populations might not be significant, is one of the group’s strategies.

“Antisemitism happens all over the place, and especially in small towns,” Lurion said. “Sometimes it comes from a lack of knowledge and ignorance, where they don’t necessarily know what the swastika represents for millions of people who were targeted — and who are still targeted today.”

Last week, the bus visited Sutton Public School, located about an hour’s drive north of Toronto. Its principal says the normalization of antisemitism and other forms of racism is what inspired her to book the bus.

“If we as an educational system don’t do something to combat that, then the normalization will continue and it’ll just be something they think is OK,” principal Jennifer Diceman said.

Solomon and Lurion are also advising the Ontario government as it rolls out mandatory Holocaust education in Grade 6 next year, a decision announced last year by provincial Education Minister Stephen Lecce in response to a spike in antisemitism.

“When we see students being targeted simply because they are Jewish, I think it is incumbent on governments to take action,” he said, noting increasing concern about the prevalence of Holocaust denial found online. “That worries me — when young people are getting information on dating sites and online and not through bonafide sources. I worry that, as a Canadian, as someone who believes in our democratic values, if we don’t have that type of knowledge instilled at a young age, I worry about the long-term impacts.”

It also means that children can be introduced to these sensitive topics with the support of an educator rather than through social media or peers.

“We’re also called in very often when schools or communities have had antisemitic incidents, but it’s reactionary,” Lurion said. “We’re going in because there has been something — whereas the goal for the bus is to reach them first, explain that this is what happened, this is the history, this is why a swastika is a big deal and this is what you can do about it.”

For Gutter’s part, the 90-year-old says he urges students to keep lighting the way toward an inclusive and accepting society.

“I want you to carry this torch,” he said. “I want you to hand it to your families. I want you to hand it to your friends. And I want you to light up the world with the flames of this goodwill of no racial discrimination and no religious discrimination and no homophobia, no xenophobia and hatred. Above all, no hatred.”

Watch full episodes of The National on CBC Gem, the CBC’s streaming service.