One morning in August 2015, a call came into Sergei Leontiev’s mansion on Moscow’s millionaire’s row. Leontiev, a late riser with a habit of arriving at the office mid-afternoon and staying until the early hours, was still at home. He was 50, with a boyish face, close-cropped dark hair and thin-framed glasses. He dressed modestly but carried himself with the confidence of a man who had co-founded a bank with his childhood best friend and turned it into a juggernaut. When he came to the phone, Leontiev had no idea what was happening at his company’s headquarters, located not far from the central bank and the Kremlin.

Alexander Zheleznyak, Leontiev’s classmate-turned-business partner, was on the line. Paramilitary troops armed with machine guns had entered the bank’s offices, he told his old friend, and they were rifling through documents on behalf of the Russian state. The bank’s assets were effectively frozen. Zheleznyak had been at Leontiev’s side long before joining the consultancy that Leontiev founded in 1988, which eventually grew into a banking group called Probusinessbank.

They now managed assets worth some $1bn and had more than 700 retail branches across the country. Together, they’d courted and won some of the most prominent western investors in Russia, including the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, Swedish asset manager East Capital and BlueCrest, the British-American hedge fund.

Zheleznyak advised his friend not to come in. “For one thing, your office is occupied,” he said. “For another, there’s nothing for you to do here.” The two agreed Leontiev would attempt to conduct business as usual, while Zheleznyak visited one of their most well-connected clients, who might help them navigate the crisis. Leontiev got into his black chauffeured Mercedes and headed to a Starbucks, where he tried to work while receiving regular reports on the raid a few blocks away.

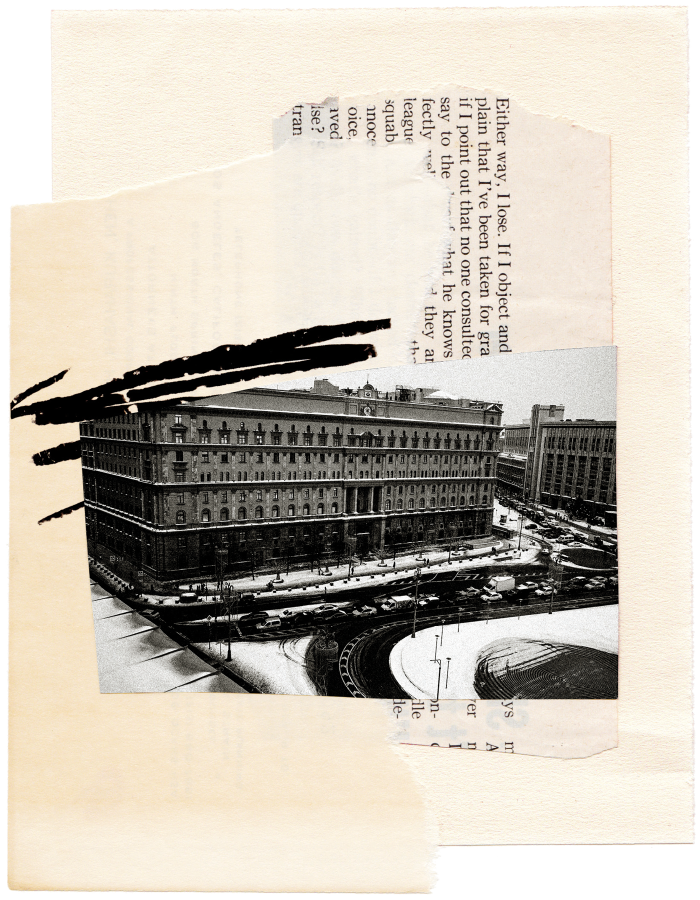

Zheleznyak soon asked Leontiev to join him at the offices of their client, Alexander Varshavsky. Varshavsky ran a large Moscow car dealership, but Leontiev and Zheleznyak allege he was also connected through his business partner to officials from the prosecutor-general’s office and to the FSB security agency, the modern-day KGB. (Their claim is supported by multiple investigations by independent Russian news outlets; Varshavsky denies the connections.) For years, Varshavsky and his business partner had given tens of millions of dollars to entities connected to Leontiev, including deposits at Probusinessbank, according to US court filings. Now, Varshavsky was nervous and volatile, worried that the money he held at the bank would not be recoverable. When Leontiev showed up to Varshavsky’s building, he sensed something was wrong. “I just smelled danger,” he later recalled.

Leontiev and his two bodyguards reached Varshavsky’s office on the top floor to find 20 armed guards waiting. He tried to enter with his security, but a skirmish broke out between the two groups. Leontiev’s side relented and he entered the office, with its windowed views over Moscow, alone with Zheleznyak. Varshavsky stressed that Leontiev and Zheleznyak would need to personally reimburse him and certain VIP clients who could no longer access their deposits.

Varshavsky then got on the phone and began making calls. Without disclosing whom he was dialling, he gave the impression he was talking to high-ranking government officials, all of whom had the ability to put Leontiev in prison if he didn’t return their deposits. (In a 2016 US court filing, Varshavsky confirmed he met Leontiev and Zheleznyak after the bank raid. In a written statement, he told us the pair had promised to fulfil “all obligations”, but never did. He did not respond to subsequent questions about pressuring Leontiev and Zheleznyak that night.) The meeting dragged on past midnight, until Leontiev convinced Varshavsky he would find a way to get the money. Instead, he went home, packed a suitcase and headed to the airport, where he boarded a flight to London. He never returned to his home country.

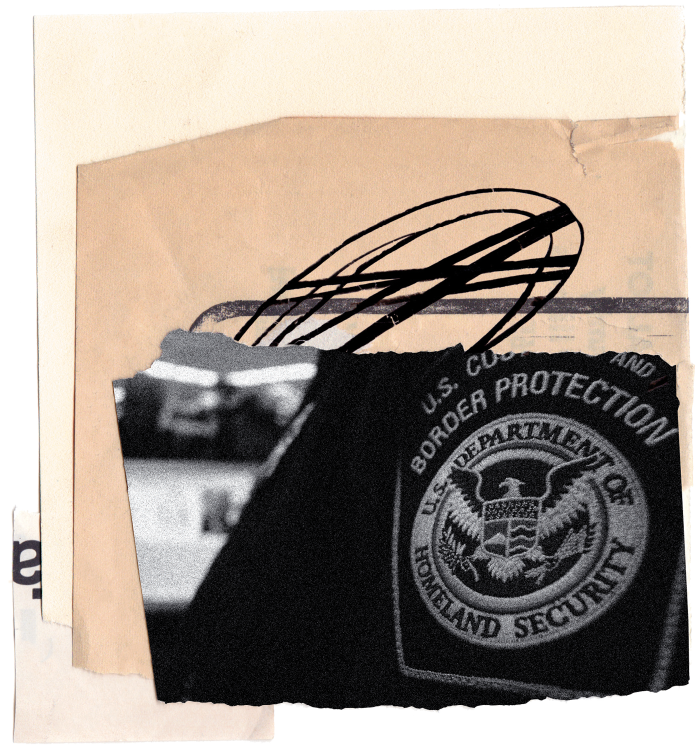

This is the story Leontiev tells of how he lost his status and his life’s work. He has been persecuted for his western-style business practices, he says, for his liberalism, for his association with Alexei Navalny, the imprisoned leader of Russia’s pro-democracy movement. He is a victim of Vladimir Putin’s vindictiveness and the corruption of the officials around him. By the time the US granted him asylum earlier this year — six weeks after Putin ordered the invasion of Ukraine — Leontiev had spent years moulding himself into the kind of political émigré Americans love most: a democratic fighter, a fair-play capitalist, an underdog.

Alice Segal, the New York judge who approved Leontiev’s asylum application, wrote in her ruling that his case had “deep similarities” to that of Sergei Magnitsky, the Russian lawyer who had been uncovering fraud by tax officials when he died in pretrial detention in 2009, causing international outrage. Were the US to reject Leontiev’s application, she added, he “would undoubtedly be jailed and tortured and deprived medical treatment as is the case with many dissidents who support Navalny”.

In early May, a Washington public relations firm offered us an interview with Leontiev, describing him as a “high-profile Russian national targeted by [the] Putin regime”. But in the process of trying to corroborate his claims with former colleagues, foreign shareholders and experts in Russian finance, a different version of events emerged. The divergence in these stories underlines the dangers of the west projecting its own expectations on to Russia and how the fog of war can obscure complex individual histories. Russian military aggression has made tales of heroes and villains more appealing. Some share the asylum judge’s view of Leontiev’s tale. But the bank insider who helped bring about his undoing eight years ago is not one of them.

Leontiev was born in Moscow in 1965, the only child of a diplomat. He did not have a typical Soviet childhood, living for a time in London, where his father worked for the Russian embassy, and later in Vienna, where his father was stationed with the International Atomic Energy Agency. Leontiev’s parents imposed few restrictions. He was uninterested in school, goading his teachers into arguments about reading he hadn’t done. Outside the classroom, by his own account, he encouraged misbehaviour, helping organise military re-enactments during which large groups of kids would hurl rocks at each other; sometimes police were called in to subdue the melee. His parents were frequently called to account for his behaviour but seemed content to let Leontiev learn from his mistakes.

One constant was his friendship with Zheleznyak, whom he met in first grade. Zheleznyak, short and eager to please, was the smallest boy in their class and had been seated in the front row so he could see. Leontiev liked to sit in the front to provoke the teachers. They developed a mutual affection that persisted through adolescence, when Leontiev’s family moved to Austria. After Zheleznyak’s father died, when he was 15, Leontiev’s parents treated him like a son, bringing him along on family holidays.

Leontiev eventually enrolled as an international studies major at Moscow State Institute of International Relations. It was the mid-1980s and Mikhail Gorbachev was gradually opening up the state-planned economy. Leontiev saw opportunities. He found a student with a photographic memory and paid him to memorise the new business regulations the country was introducing, then offered up his expertise through paid lectures, giving the classmate a cut of the profits. Soon, Leontiev moved on to other enterprises: a travel insurance firm, a tourism company.

Zheleznyak, meanwhile, planned to become a criminal defence lawyer. Both his parents had been respected criminal lawyers, and he dreamt of following in their footsteps. He graduated from law school and found work defending clients accused of murder and robbery as well as white-collar criminals involved in the nascent banking sector, he told us. He suggested to Leontiev that banking would be a profitable business.

Zheleznyak said he had no intention of quitting the law but that Leontiev pushed him into it, first asking him to help draw up legal paperwork for a new consulting venture and then pressuring him to join. “Are you a friend or not?” Zheleznyak recalls Leontiev asking. “Of course, I didn’t manage to wriggle out of it,” he recalled recently. “I quit my beloved work.” Leontiev puts it more positively. “I always saw the spirit of an entrepreneur in him. My role was to create an alternative option for him.” In 1993, they received a banking licence that would launch Probusinessbank, a company that would make them both millionaires. (Later, as they added a number of other financial companies to their stable, they paid an agency to come up with a brand for the entire group. The result was a single word: “Life.”)

As partners, Leontiev and Zheleznyak divided and conquered. Leontiev cultivated a reputation as an intensely driven visionary. He put in 14-hour days, regularly scheduled 10pm meetings and ended his evenings with an hour-and-a-half-long run on a treadmill at maximum incline. Zheleznyak, the extrovert, wooed clients, including Varshavsky, who had helped launch one of Moscow’s first luxury-car dealerships. Zheleznyak and Varshavsky had common interests — both were attracted to a moneyed lifestyle, Zheleznyak said — and they became friends, spending time with each other’s families including birthdays.

Leontiev admired western entrepreneurs such as Warren Buffett and Richard Branson. His principles included “people make decisions — not paper” and “no stupid banking rules”, rebukes to the Soviet-style bureaucracy that lingered at many competitors. While other banks used credit scoring, Leontiev devised a system where credit managers would determine whether to approve a loan based on their personal interaction with a client, pending the approval of a risk manager. The bank used role-playing logic games in hiring interviews and employees’ wages were tied to the performance of their clients’ loans.

Leontiev’s supporters saw a genius on the verge of remaking the traditional banking industry. Detractors saw him as a risk-taker trying to disrupt a sector that requires stewardship of customer deposits. But between 2006 and 2012, the assets of Probusinessbank and its banking affiliates were growing at an average rate of 56 per cent a year — three times faster than the Russian banking sector overall, according to Kommersant, a leading Russian newspaper.

By 2012, Leontiev and Zheleznyak were running a business with a retail presence in nearly every important Russian city. It was only the 34th largest bank in the country, but it was growing fast and had high margins. Meanwhile, Putin’s image both in Russia and on the world stage began to change, as it became clear he would not let go of power and planned to use it differently.

Not everything at Probusinessbank had gone smoothly. Leontiev spooked some of his investors and executives in 2010 when he set up a trading room to invest in high-yield foreign stocks, ranging from BP to WholeFoods. Employing capital and personnel from the bank to run an operation making trades was inconsistent with a mid-sized retail bank, according to several individuals close to the shareholders. “People have different perspectives,” Leontiev told us. “My general view was to create . . . this new type of investment platform. That was a much grander, much bigger project.” Leontiev eventually shut down the operation, he said, due to the unfavourable regulatory environment and in response to opposition from shareholders and other executives. Instead he created a separate venture called Wonderworks to make similar trades. It was funded by loans from the banking group that were eventually repaid.

In 2012, a marketing guru at Life named Slava Solodkiy suggested that Alexei Navalny speak at one of the bank’s regularly scheduled conferences for branch managers and employees. Navalny made his name exposing embezzlement at Russian state-owned companies and became the country’s most prominent opposition figure. Leontiev and Zheleznyak agreed, and Navalny, fresh from the biggest anti-government protests of the Putin era, spoke at the conference about reform. Not long after, executives at one of the bank’s affiliates — an internet bank called Bank24.ru — discussed the possibility of issuing a Navalny-branded credit card that would give a 1 per cent cashback reward to his non-profit. But the idea was soon scrapped amid worries about political blowback.

In March 2013, Putin appointed Elvira Nabiullina as Russia’s new central bank governor. Nabiullina, a brainy technocrat, had helped steer the country through the 2008 financial crisis as economic development minister, and her appointment was welcomed by western investors. Soon after, the central bank began to clean up the country’s bloated financial sector, where many lenders served as so-called pocket banks for their billionaire owners or were engaged in irregular offshore behaviour and money laundering. Nabiullina would ultimately wind down more than 300 lenders in her first few years in the post.

The following year Bank24.ru attracted the central bank’s attention. It had been spun out from Probusinessbank’s holding company but still had ties to its former parent, when Leontiev and Zheleznyak heard the regulator was preparing to investigate it. The pair met with Nabiullina to make the case that Bank24.ru should retain its licence. At the meeting, Leontiev began lecturing Nabiullina on the ins and outs of banking regulation, one person with knowledge of the meeting recalled. “She was pissed off, because he was lecturing her about how to do supervision in the country,” they added. The meeting ended shortly thereafter.

The central bank denied this characterisation of the meeting. A spokesperson said the central bank arranged the meeting after Bank24.ru violated anti-money-laundering legislation more than once. They denied that the meeting was the reason Bank24.ru’s licence was revoked a few weeks later.

It was around this time, Leontiev and Zheleznyak said, that they began facing pressure to sign over their ownership stake in the banking group, in return for political protection. They claimed this pressure came from Varshavsky, his business partner and their associates in the Russian prosecutor-general’s offices. The Russian state was consolidating control over sectors of the economy including banking. A few oligarchs were in the crosshairs while other Putin allies gained influence, and Varshavsky, they alleged, implied that the two co-founders would need protection if they wanted to hold on to their empire. Zheleznyak said he went as far as to meet with the then-head of the FSB’s economic unit, Kirill Cherkalin, who suggested installing a retired FSB officer as a vice-president at the bank. (In 2021, Cherkalin pleaded guilty to taking bribes from a different Russian company, was found guilty of large-scale fraud and sentenced to seven years in prison.)

Leontiev and Zheleznyak said Varshavsky kept urging them to give up control of the group, at one point drafting documents that would transfer their shares to his holding company for the ultimate benefit of the then-prosecutor-general and one of his top deputies. (The prosecutor-general at the time did not respond to a request for comment.) Varshavsky, who responded to questions via email, denied pressuring them to give up their stakes and denied having any ties to the Russian prosecutor-general or high-ranking officials. However, investigations by Novaya Gazeta, an independent newspaper, and by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, reported links between investors in his company, Avilon, and family members of Russian security services officials.

Leontiev’s western shareholders began to notice something was amiss. “It was nearly impossible to sort of read Sergei and miss the nervousness that was just getting worse and worse,” said one person close to the shareholders. The departure of some top executives did not go unnoticed, according to two western shareholders and one former executive at the bank. Why, they wondered, did the company’s English-speaking employees — the ones who met with western shareholders — keep leaving?

One senior Probusinessbank executive, Peter, said he became aware of three suspicious “schemes”. (Peter is not his real name. He spoke to us on condition of anonymity, citing concern for his safety.) In one, documents showed the bank was posting losses on foreign-exchange operations with counterparties in Cyprus. But it was impossible to track where the money was actually going. In another, the bank had issued loans to offshore shell companies with scant public profile and dubious ownership. Peter said he also witnessed conversations that made him suspect some of the bank’s securities were being used as collateral in Cyprus, even though there was no reflection of this on the bank’s balance sheet.

By late 2014, Nabiullina’s clean-up of the Russian banking sector was well underway. The market was starting to reflect investors’ concerns. That autumn, Fitch Ratings downgraded Probusinessbank because of concerns about the liquidity of the bank’s security portfolio, then later ended its coverage of the bank altogether, citing a lack of sufficient information. Peter worried that if the central bank came after Probusinessbank, he could be criminally implicated. He decided he had to act.

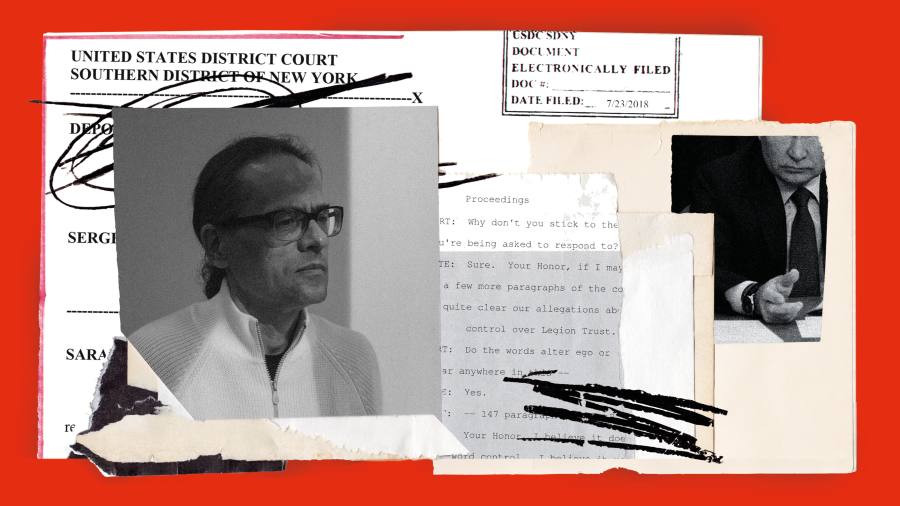

In mid-May this year, we met Leontiev at the Manhattan offices of his lawyers, Kobre & Kim. The years have transformed him, his once-neat black hair a greying ponytail. His face looked gaunt, and his clothes hung loosely from his frame. He spoke in short sentences, without much emotion, at times as if he were bored by his own story.

At the meeting, Leontiev declined the lunch of deli sandwiches offered by his lawyer. He was keeping similar hours to those that fuelled him as a young entrepreneur, subsisting on one meal a day, a late dinner around 2am, shortly before bed. But these days, his primary occupation was fighting legal battles, including one in Liechtenstein where some funds he put into a trust have been frozen. At one point, he likened his legal situation to the siege faced by Ukrainians in Mariupol and, at another, to the Battle of Stalingrad.

In sometimes halting English, he described an elaborate series of risk-management techniques that he used to guide everything from his investment decisions to his legal battles to death threats against him. “I have this type of market-oriented approach to life,” he said. “It’s not how big the risks are, it’s your quality to manage the risks you should have.”

After he fled Russia in 2015, the authorities there alleged Leontiev and others had orchestrated an offshore money-laundering scheme. The central bank announced it had uncovered a roughly $1bn hole in Probusinessbank’s balance sheet. Six staff were arrested; four were sentenced to up to seven years in Russian penal colonies. The authorities sought to extradite Leontiev and Zheleznyak, who hired lawyers to fight back. Shortly after they fled Russia, Zheleznyak pleaded with his friend to talk to Varshavsky again. The three met at a high-end hotel in Mayfair. Leontiev surreptitiously recorded their conversation on the advice of his lawyer.

“You have an obligation toward us in the neighbourhood of 100 million,” Varshavsky told them.

“Yes,” replied Leontiev.

“Do you have this money today?”

“[We] have it, 100 per cent,” Zheleznyak interjected.

“We have personal assets, yes,” Leontiev added.

“Well, it doesn’t matter if they are personal or not —”

“We have it,” Leontiev said.

Before they left the meeting, the transcript of which was later introduced as part of discovery in a 2016 court case, Leontiev seemed to blame Varshavsky for failing to use his connections to avert the collapse of Probusinessbank: “When our enemies broke our business, you were unfortunately unable to help us. And this caused a chain reaction and consequences for you, because the goose that laid the golden eggs was slaughtered.”

Varshavsky expressed fear for his own fate if he was forced to return to Russia with no guarantee of recouping his lost investments. And he gave them a stark warning: “There may be a point of no return,” he said. “Then nobody will need your money. Now that is the scariest thing that could happen.”

Soon afterwards Leontiev moved to the US, where he settled in Manhattan and set up a new investment firm. He told us he funded it with the proceeds of Wonderworks investments before Russia filed criminal charges against him and began petitioning to freeze his assets. For several weeks, he said, cars would wait outside his apartment building and tail him to work. One weekend, someone tried to break into his firm’s office.

Zheleznyak, who had resettled with his family in the Boston suburbs, also felt mounting pressure. Friends of his children began receiving threatening messages in badly written English on social media. In Moscow, someone found photos of Zheleznyak and young family members on his parents’ grave — which he interpreted as a warning that they could be six feet under next.

A slew of court cases were brought by different arms of the Russian state and by former Probusinessbank clients around the world. Varshavsky’s car company Avilon was among those suing Leontiev and his associates for approximately $60mn in New York state supreme court, accusing him of transferring money it had loaned his companies to an offshore trust. (Leontiev rejected the allegations. Avilon and the others eventually dropped the case.) Russia’s Deposit Insurance Agency (DIA) brought claims against Leontiev in Austria — where his parents were summoned for questioning — and Cyprus. These moves follow the agency’s pattern of pursuing bankruptcy or discovery proceedings in international courts, in an attempt to get visibility on a target’s assets.

Jonathan Reich, a corporate lawyer who initially took a job at Leontiev’s financial services firm before becoming head of his legal efforts in half-a-dozen jurisdictions, told us that Russia’s strategies to destroy Leontiev have evolved over time. But the aim throughout, Reich alleges, was to tie Leontiev up in expensive court battles and sap his will to cling on to his assets.

In a written statement, the DIA denied that it had “political interests” in pursuing Leontiev abroad and said its main objective as an agency was the “maximum possible replenishment of the bankruptcy estate”, in order to satisfy creditor claims and alleged that Probusinessbank’s owners had artificially inflated the bank’s assets to hide its true financial state.

When we asked former associates of Leontiev’s whether they thought he had committed the fraud Russian authorities allege, a few hypothesised about what might have happened, but none had proof. “He maybe lost money within the bank because of poor risk policies,” one former bank executive said. “But he’s not a thief.” (Leontiev dismissed this characterisation of his risk policies as “ignorant”.)

Several people involved in the bank at the time questioned the assertion that Leontiev’s problems with the authorities stemmed from his involvement with Navalny. Solodkiy, who had invited Navalny to the bank’s 2012 conference, told us he had spoken to Leontiev on many occasions about the opposition leader, and that Leontiev had expressed solidarity with his political views. But one person close to the shareholders said “the bank wasn’t political at all”. Zheleznyak said he wasn’t surprised the western shareholders would think this. “Sergei and I always emphasised business first and didn’t discuss politics broadly within the bank,” he told us.

In January 2021, Zheleznyak created a US branch of Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation, with the blessing of Navalny’s chief of staff, Leonid Volkov. Since then, Leontiev has given the foundation a monthly donation of $20,000, Volkov told us. Before that, Leontiev had been giving to the foundation’s Russian legal entity, Volkov said, but he did not know how much exactly. Volkov said the foundation attempted to vet Zheleznyak and Leontiev’s story. “We had to rely on the people we trust. Can I sign it with my blood that they didn’t steal anything from their bank? No, I can’t.” But ultimately the story he found credible was the one told by Leontiev and Zheleznyak, not the Russian government.

Over the course of our reporting, one person mentioned the name of the senior executive, Peter, who they said had warned them “something fishy” was going on at the bank. We independently confirmed Peter’s identity with five people and his stint at the bank with three of them. He rejected the assertion that Leontiev had been politically persecuted in Russia because of his links to Navalny. “This whole story is a story of embezzlement,” he said in a phone call. “There is no political case . . . [Leontiev] was not involved in politics. He was involved in only one thing: stealing money from the bank for his own account through Cyprus, and from the offshore accounts.”

Peter alleged the reason the central bank opened an investigation into Probusinessbank in the first place was because it received evidence of embezzlement. Then he confided how he knew this: he had provided the documents himself.

A few weeks later, over plates of linguine and parmigiana, Peter detailed his discoveries at Probusinessbank back in 2014. He described thinking over his possible moves. He knew someone at the Russian central bank through a mutual acquaintance. Through this person, they arranged to meet at a bar on the outskirts of Moscow. Peter said he brought a small sheaf of papers offering some evidence of the alleged fraud. More covert meetings, arranged via a burner phone, followed. Each time, the official asked Peter to provide additional documents.

Peter provided us with the name of the central bank official, but said he hadn’t spoken to them since their last encounter seven years ago. The official, whose identity and employment at the bank we independently confirmed, asked to remain anonymous for their personal safety. They were pessimistic about the political situation in Russia following the invasion of Ukraine, calling it “Orwellian”. But they were adamant that this did not change the underlying facts of the Probusinessbank case. They supported Peter’s account. Peter had been “extremely scared” during their first meeting, they recalled. Because Russian courts require that banking documents be obtained through legal searches, the central bank was never able to use any of the files Peter handed over in its case against Probusinessbank. But those documents provided a map of where to look.

The central bank official said they never told anyone who the whistleblower was, not even central bank colleagues, because they had been so alarmed about the potential repercussions. Leontiev and Zheleznyak were correct that there had been political pressure in the case, they said, but it was the central bank official who had been on the receiving end. Probusinessbank, they claimed, had “very powerful backers”, and there had been huge strain on the central bank and on them personally, from the outset, not to open an investigation into the lender. They described the situation as like something in a Tom Clancy novel. They only persevered, they said, because of the strength of Peter’s documentation: “The files we submitted were so clear.”

The narrative of Leontiev’s rise during the liberalising of Russia’s economy after 1989, his fall during the increasingly authoritarian 2010s, and his escape from political persecution to freedom-loving America, has an attractive consistency. It chimes with what we already know about Putin’s Russia, a state that aggressively pursues its enemies, without regard for borders or morality. It is this narrative the New York court cited when it granted him asylum. But the accounts given by Peter, his Russian central bank contact and several of Leontiev’s former associates complicate the picture.

Leontiev changed his description of events a number of times during a series of meetings in person and over video, often appearing to have little patience for detail. “I’m such a person that for me, it’s much easier to invent something than remember,” he said, of trying to recall minutiae.

In November, we spoke to Leontiev a final time, presenting him directly with Peter’s claims. As we described the allegations over Zoom, his face remained impassive. He seemed neither angry, nor surprised. In Russia “the culture is just lying, lying, lying,” he told us. His next reaction was that the person was just a “stupid idiot” who took a “small chain” of the bigger story but misunderstood it. Maybe the whistleblower had a hidden agenda. Maybe the whistleblower was from JPMorgan, he wondered aloud at another point, without elaborating. Whoever it was, he was not interested in learning the person’s name, he claimed.

As for the way some of the offshore deals were structured, Leontiev said that it had been up to other top executives, auditors and consultants “who were just telling me and giving me the level of comfort that everything was really structured and that we’re doing nothing wrong”.

At this point, Reich, Leontiev’s lawyer, interjected, saying that the practices described were in line with the law and market practice activities, particularly for mid-sized Russian banks at the time. “I think it fundamentally mischaracterises it as something nefarious or an attempt to funnel or siphon money out of the bank,” he said, “when it was really functioning as the plumbing for the finances of the bank itself.” Zheleznyak, who says he faced extortion from the Russian authorities, made a similar argument, saying such transactions were a means to support the bank’s capital requirements and were neither secret nor illegal. The security loan transactions had involved major Russian brokerages, he noted.

Leontiev questioned why the Russian authorities would have waited a year to bring criminal charges if they had such impressive evidence, and asked why the whistleblower had never testified in any proceeding or presented his evidence in court. In a follow-up email, Leontiev said courts outside Russia had “found in our favour and rejected the Russian government’s allegations against us.” He rejected the central bank official’s assertion that Probusinessbank’s backers could have influenced the regulator. “The idea that we could pressure Nabiullina and [the central bank] somehow is a joke,” he wrote.

The Russian government’s decision to go after him was due to his political associations with Navalny. That was the only narrative consistent with reality, he insisted. “I’m one hundred per cent sure.” He added: “I was a real threat for them.”

Leontiev and Zheleznyak continue to deny wrongdoing. Leontiev and his legal team are still waiting for the resolution of court cases in Liechtenstein and other countries. In December, Interpol granted his appeal to be removed from its watch list, allowing him to travel, for the first time since 2015, to see his elderly father in Austria. Reich alleges Russian authorities manipulated the situation. “One of the most insidious ways in which Russia has gone about alleging criminal activity by Sergei and his colleagues has been to take perfectly legal and standard corporate transactions and only show a part of them, or contort their description of them, in order to argue that this is suddenly embezzlement, or this is a fraudulent conveyance, or this is misappropriation of funds. And that’s really, really hard to disprove,” he said.

It is difficult to know whether Leontiev or the whistleblower is lying, or whether both are telling their own versions of the truth. Russian entrepreneurs who built companies in the post-Gorbachev period enjoyed rapid growth, courting a blossoming consumer class along with western investors and becoming millionaires or billionaires in the process. But corruption was rife. In 2012, the year before Nabiullina became central bank governor, $49bn left Russia in illegal capital flight, according to official monitoring of the commercial bank sector. Sometimes the fraud was homegrown, but at other times it was forced on business leaders by government officials, who pressured them to hand over shares, cash or a percentage of their transactions. Those who refused or tried to expose corruption faced potentially severe consequences. Magnitsky was only the most notorious example.

Just as not all Russians living in exile will be political freedom-fighters fleeing Putin’s wrath, so not all the business reforms implemented in Russia in the 2010s were born of corrupt intent. Nabiullina’s efforts to clean up the banking sector were celebrated for years by western policymakers and institutions. The central banker has now been sanctioned by the UK and US for enabling Putin’s brutal war on Ukraine by propping up Russia’s economy.

During our first meeting in Manhattan, Leontiev told us that before the pandemic he and his wife liked to attend the opera in New York. His wife liked the music; Leontiev enjoyed soaking up the gilded atmosphere. Most of all, he liked the moment when the entire mood in the theatre changed during a crucial tension in the music. It was in that moment, he said, that you could finally ascertain the true artistry of the performance. “You distinguish, is it real? Is it authentic? Or is it just something which is a copy?” He paused. “And that’s the moment I like.”

Courtney Weaver is the FT’s US business and politics correspondent and a former Moscow correspondent. Stefania Palma is US legal and enforcement correspondent

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first