You’re a hedge fund manager with a big idea. US lawyers are recruiting plaintiffs for a class action that echoes one of the great short trades in recent years. You have spotted the angle but it seems the wider financial community has not.

You short the companies involved, of course. But court procedure moves at a glacial pace and evidence underpinning the claims isn’t clear cut. Returns are uncertain and borrow is expensive.

Should you campaign to push the story into the mainstream? Even if it’ll make a lot of people think they might have cancer?

The above scenario is as plausible as any when trying to explain how Zantac became one of the markets stories of the year. Suddenly in August, apropos of nothing, pharma investors panicked about a potential multibillion-dollar liability around the heartburn treatment and crashed the market value of its makers by approximately $40bn. Figuring out what happened needs some history.

Zantac (aka ranitidine) was one of pharma’s first blockbusters, meaning sales of more than $1bn a year. The pill was a key product for its inventor GSK through the late 1980s and early 1990s.

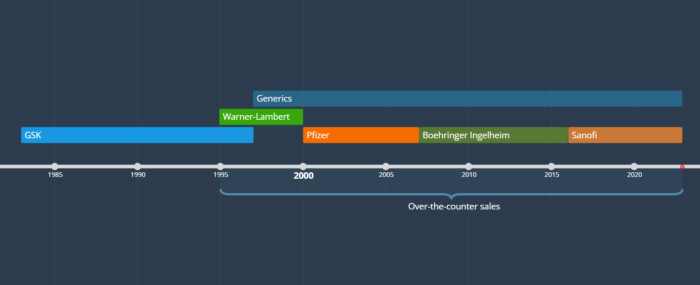

From 1995, Zantac was sold in the US without prescription. Patent protection lasted until 1997, with ownership of the brand passing around in the years before and since. Here’s the ownership timeline:

[Zoom]

In September 2019, the FDA responded to research that found elevated carcinogen levels in Zantac pills by issuing a safety alert and beginning its own tests. These showed contamination strengthening over time in normal storage conditions, and that both age and higher temperatures worsened the effect. Zantac was officially pulled from the US market in April 2020.

Zantac’s withdrawal was a big consumer story but in financial circles it barely registered. A search of corporate earnings calls suggests the drug was hardly mentioned between 2016 and 2021 and its name appears only in passing in broker notes, usually in relation to Sanofi and generics maker Perrigo. GSK shares fell about 10 per cent between the FDA’s first and final Zantac alert, but the loss was on an entirely unrelated profit warning.

The first twinge of Zantac anxiety arrived on June 24, 2022, when law firm Baum Hedlund Aristei & Goldman issued a press release that set out a trial schedule in California State Court. The release quoted Brent Wisner, Baum Hedlund’s celebrity attorney.

Wisner was co-lead counsel in 2019 lawsuits against Bayer and its new owner Monsanto over claims the Roundup weedkiller had caused cancer. The landmark trials resulted in product-defect awards in excess of $2.4bn, among the biggest in US history, and put him on the cover of Super Lawyers magazine:

The same legal team was deploying the same playbook on Zantac, with Wisner saying:

“Thousands of people suffering from cancer after taking Zantac have been waiting and waiting to have their day in court . . . It is nice to be able to tell our clients that the litigation is picking up some steam, and that we will soon be able to show a jury that the makers of Zantac knew as far back as the early 1980s that the drug can cause cancer. They need to be held accountable for putting profit over people.”

That hedge funds were quick to the news should be no surprise. Roundup settlements had created one of their most lucrative trades of the last decade — albeit largely by accident. Bayer’s fundraising for its $63bn takeover of Roundup maker Monsanto in 2016 included the unusual mechanism of a mandatory convertible bond. Hedge funds bought the notes then delta-hedged by selling the stock short, knowing that they could close those positions on receiving the converted shares three years later.

It proved quite the fluke. Between the first Roundup trial hearing in 2016 and a $10.9bn settlement in 2019, Bayer stock halved.

Nevertheless, equity investors seemed slow to make any connection. GSK even set out Zantac litigation exposures in a prospectus for a spin-off of Haleon, its consumer business, on the first day of June; its shares were barely changed that month, and the next.

Zantac’s first mainstream public mention came during the Q&A section of a Sanofi earnings call in late July. Then on August 5, Morgan Stanley analyst Mark Purcell and his team covered the theme at length in a note on GSK:

There is considerable uncertainty at this stage surrounding the potential financial impact of the Zantac litigation, which could create a news flow overhang and impact management’s flexibility to deploy the balance sheet to drive growth and innovation. Taking precedent litigation settlements would indicate a possible range of $10.5-45bn for the total Zantac liability and, using our high-level assumptions based on time of ownership and market exposure of Zantac, a possible Zantac product-liability of $3-27bn for GSK.

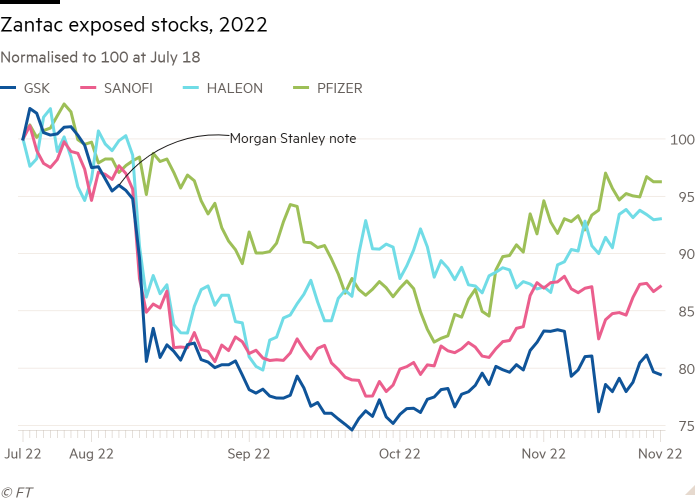

Within a few days GSK was at the centre of the story. Below is a performance chart of Zantac-exposed stocks normalised to July 18, Haleon’s first day of trading post spin-off. It shows GSK, the dark blue line, being hit hardest and taking longest to recover.

The violence of the market reaction can probably be explained by the financial-market equivalent of post-traumatic stress disorder, CFRA analyst Nicholas Rodelli said in a recent note.

“With rare exception, this category of slow-moving mass tort exposure tends to plod along for years, usually only crossing over into the investment case on occasion, and largely at the margin,” he said. But Roundup, along with 3M’s potential multi-billion-dollar legal exposure to faulty earplugs, had been the “tape bombs” that changed investor psychology, he said.

Even before the slump, bets against GSK had been increasing rapidly. Markit data show total short interest spiked from a 10-year low equivalent to 0.01 per cent of its free float on July 15 to a 10-year high of 1.66 per cent of free float by September 14.

Which funds were short? We can’t say for sure, because one of the perks of targeting a UK-listed large cap is invisibility. The FCA register only requires disclosure when a private short position reaches 0.1 per cent of the issued share capital, which for GSK at its current price would mean a wager in excess of £56mn. No firm has ever hit that threshold.

(In the course of researching this post we contacted a number of US-based hedge funds rumoured to have bet against Zantac makers. None would comment on the record.)

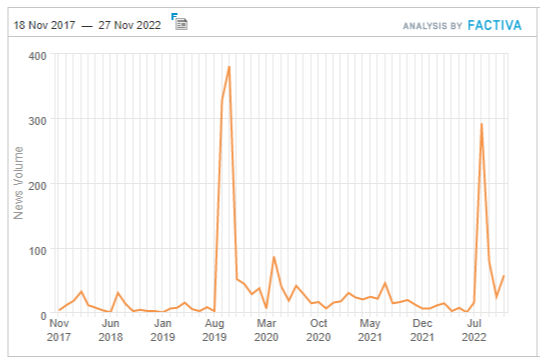

The self-reinforcing effects of a stock market sell-off made Zantac as big a story in August 2022 as its was through the 2019 recall — except this time, it was all about the makers. The below chart is a Factiva global media search for articles about Zantac and cancer for the last five years:

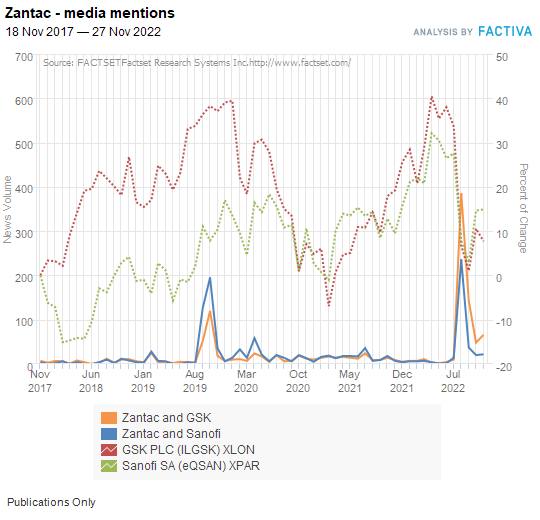

And here’s how many of those articles reference either GSK/GlaxoSmithKline or Sanofi, overlaid on their share prices:

[Zoom]

None of the above adds clarity to the question of whether Zantac causes cancer. Drug companies say it doesn’t and the lawyers pursuing them say it does. Both sides cite from an huge, ever-growing body of academic research around the question of how much N-nitrosodimethylamine is too much. Both sides argue, for example, that an epidemiology study published in September supports their arguments.

What ought to be more straightforward is that Zantac isn’t Roundup. One is a drug and the other isn’t.

Unlike weedkiller, prescription drugs are governed by a regulatory regime of pre-market trials and post-market oversight including strict labelling controls. The hurdle for admissible evidence in trial will therefore be much higher, meaning the percentage of claims a court might consider will probably be lower.

GSK and peers will soon hear the results of so-called Daubert hearings, held in September, that determine what expert evidence can be admitted into trial. Already, however, the worst-case liability has been shrinking. The scope of litigation was narrowed from 10 cancers at launch to five “focus” types and of these, experts have questioned whether the evidence will be strong enough to pursue damages for bladder cancer. According to Morgan Stanley, bladder cancer makes up nearly two-thirds of prevalent cases.

As unclear as the size of any liability is the scope. Generic drugmakers are generally protected by the US Supreme Court against personal injury claims and the practice of holding the brand owner to account for generic sales (known as innovator liability) is highly contentious. Zantac’s convoluted ownership history makes apportioning blame impossible on public data alone. And recent precedent suggests that even the sellers of branded drugs are afforded some protection, with the FDA wearing partial responsibility for getting the warning label right.

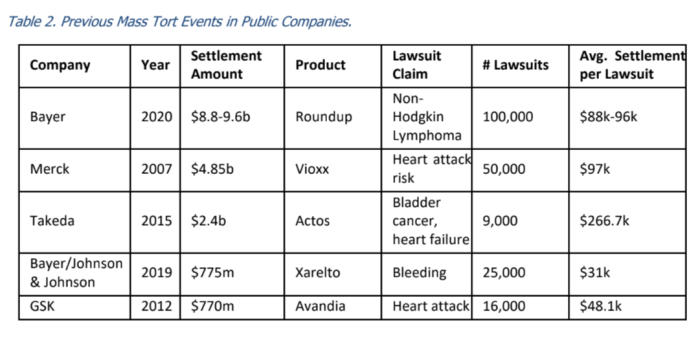

Moreover, Roundup tape bombs were caused largely by three jury verdicts Wisner’s team landed in California state court. Those made it an outlier among US personal injury awards; table below from CFRA:

Morgan Stanley had initially forecast that a total ~150,000 Zantac claims would be filed, and that the average settlement would be between $75,000 and $300,000.

On October 12, after taking feedback from an unidentified legal expert, the broker published a follow-up note. The expert suggested a total of 50,000 patients was more realistic, assuming all five “focus” cancers make trial, and that the average settlement would be between $100,000 and $150,000.

Using those forecasts, the total liability for all five Zantac makers fell to between $5bn and $7.5bn, rather than the up to $45bn Morgan Stanley had initially estimated.

The next incoming tape bomb will probably be from a Florida court where a ruling on the submissibility of evidence (the Daubert hearing) is due imminently. Recent demand for call GSK and Sanofi options suggests hedge funds are positioning for positive news (and/or taking profit). Likewise Markit data showing that GSK shares on loan down 60 per cent since mid September.

Once again, however, equity investors have been sending out a different message. In a flat wider market GSK remains worth about $20bn less in market cap terms since the start of August, while Sanofi is cheaper by approximately $10bn, even after a bounce from September lows. It seems that while cancer scares can be hyped quickly, recovery from PTSD needs more time.

Further reading:

— US Lab at the centre of legal fight over Zantac and cancer – FT

— Pharma groups lose £30bn on heartburn drug lawsuit worries – FT

— GSK’s delayed-onset chronic spin-off reflux – FT