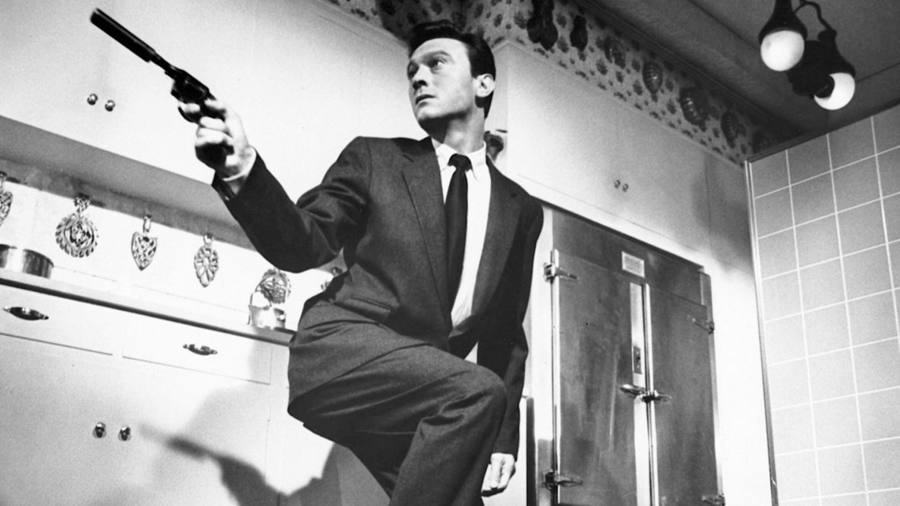

Is Quentin Koffey Wall Street’s Manchurian Candidate? In the cold war classic film, an American soldier is brainwashed by a hostile foreign power into unwittingly bringing down the US government.

Koffey is a well-known activist investor who, after stints at Elliott Management and DE Shaw, now has his own hedge fund, Politan Capital Management. He is seeking a board seat at Masimo Corp, a California-based maker of pulse oximeters with an enterprise valuation of $8bn.

Koffey and Masimo are at odds about the company’s direction. Its share price is down more than 50 per cent this year after a poorly received acquisition. Koffey seeking election to the Masimo board is itself nothing extraordinary. These clashes happen dozens of times every year in the US. Yet the Politan/Masimo fight has captivated Wall Street for a particular reason.

Masimo does not think it should be so straightforward for Koffey to stand for election. It is insisting that the investor disclose the specific identities of his largest fund backers. Masimo has even gone as far as speculating in legal filings that Koffey just may be a “Trojan horse” representing “sovereign entities that do not respect — and have attempted to steal — intellectual property belonging to US companies”.

The Masimo board has been careful not to explicitly accuse Koffey of being a foreign agent or of having malign motives. Rather, they believe Masimo shareholders deserve to know who is behind Politan before allowing Koffey to seek a board seat. Koffey disagrees, saying Masimo’s information requirements needed to stand for election are both irrelevant and legally impermissible. He is asking a Delaware court to invalidate the requirements.

US companies with the court’s backing have increasingly been free to create hoops for dissident investors to jump through before waging proxy contests. But the set of requirements Masimo is seeking to impose has the investment and legal community wondering if this time corporate America has pushed the envelope too far.

The Politan/Masimo fight has erupted at a crucial moment in activist investing. The US Securities and Exchange Commission has just rolled out the so-called “universal proxy card” that makes it easier and cheaper for shareholders to run against company-backed directors. The worry for companies is that now marginal or unsavoury shareholders can seize upon the universal proxy to snatch board representation.

Corporate lawyers are advising incumbent directors that they can impose some order on board elections through a mechanism known as “advance notice” provisions in company bylaws. These provisions tell dissident shareholders by what date they need to submit their board nominations and what kind of biographical and background information they must provide to the company to be eligible for ballot placement.

Advance notice provisions tended to be mild. In some instances, however, information shared would go on to reveal that a director nominee had previously unknown ties that could be sinister.

Still, companies figured out that advance notice provisions could be strategically deployed to frustrate or even thwart dissident shareholders. Courts generally deferred to companies that chose to strictly enforce technical rules around submitting nominations that kept out dissident nominees.

Masimo may now be overplaying its hand. The worry for companies and corporate lawyers not involved in this dispute is that Masimo’s advance notice requirements will be judged to have gone too far and that the Delaware court may finally curtail advance notice provisions as a general matter.

Koffey says that Politan has confidentiality obligations to its backers and regardless, those backers have totally passive stakes with no control over his decision-making. Besides disclosing the identities of Politan’s investors, Masimo is demanding information on past and future Politan activist campaigns as well as details of investment holdings of these backers and even their household members with the theory that those details could show conflicts of interest.

“The bylaws protect against a ‘Trojan Horse’ situation where a nominating stockholder and its director nominee are acting on behalf of — and potentially sharing confidential information with — undisclosed actors who do not have Masimo’s best interests in mind,” writes Masimo in its court filings.

It may be that Koffey has bad ideas and bad intentions for Masimo, as the company’s board worries. But the question really is why does the board get to cut off the debate on both Koffey’s ideas for the company, as well as whatever shortcomings he brings, without permitting shareholders to decide those questions for themselves.